Why the AI Water Issue Has Nothing to Do With Water

A psychological autopsy

I. An issue of unfading importance

A curious phenomenon is unfolding in discussions about AI: a disproportionate fixation on water.

More than copyright breaches, dubious labor practices, and overblown promises, the anger of certain demographics—young people, progressive activists, AI ethics advocates—has converged on the fact that corporations waste so much water (with the sole finality of creating AI models that careless consumers will later use to flood the world in slop) that they may as well cut us access to the canal network or the hydraulic grid outright.

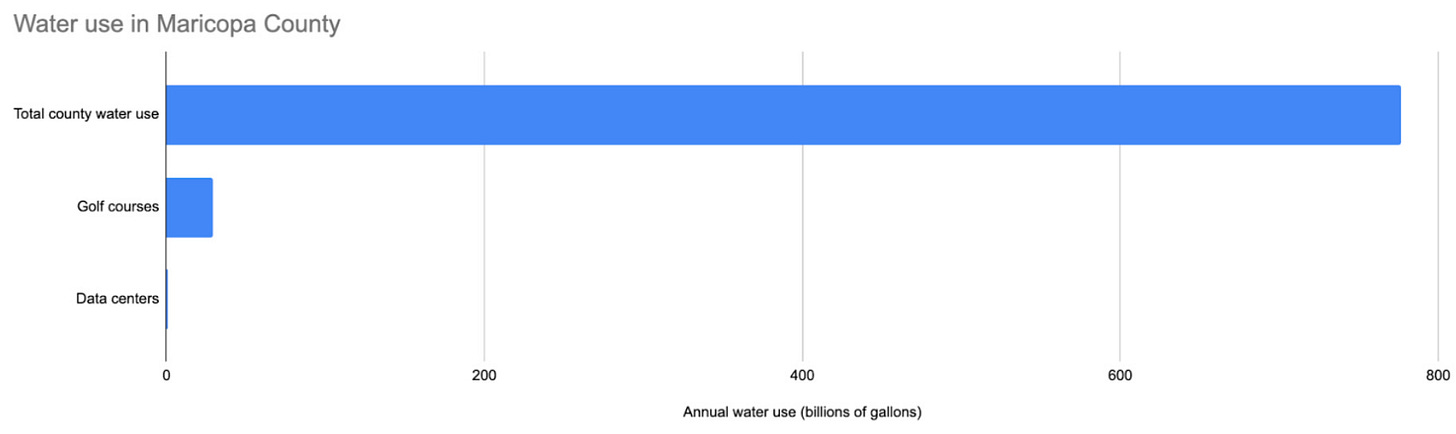

It rains, but we don’t see a drop, they argue. Specifically, they seem to be worried about the water that’s needed to cool the data centers that train and run the models. Given the pervasiveness of the water issue in the anti-AI discourse, it might come as a surprise to learn that the actual scale of the problem has been thoroughly exaggerated.

Just to be clear: these two facts can be right at the same time: 1) The AI industry has done some reproachable things, 2) wasting water is not one of them.

Perhaps the highest-profile debunked case comes from a mistake in The Empire of AI, a book that became a bestseller and helped popularize this concern, authored by tech reporter Karen Hao (whom I greatly respect as a voice calling out AI companies for doing things the wrong way). To summarize what happened: Hao cited water usage figures that were off by a factor of one thousand (x1000), and it took exhaustive investigative effort by Andy Masley to set the record straight (he is the main source I will cite throughout as I consider him, albeit not a professional journalist, the leading expert on the topic).

Hao issued a correction following Masley’s investigation (he commended her for this, and I do, too), but she didn’t modify the main thesis of the water chapter in the book, despite the corrected numbers implying a significant reduction in the relative importance of the water issue, a core driver of the whole anti-AI narrative. And yet, despite Masley’s sweeping work (which goes well beyond this specific mistake in Hao’s book; it just happens to be the example that went viral), the perception of the water issue lingers, seemingly immune to factuality.

It’s fair to assume that neither Masley’s work nor Hao’s correction has yet had time to settle in the collective awareness—I have not seen a single post about either beyond my immediate circles—but I suspect it won’t matter: The water issue is not about water.

This is, as you may suspect, not an article about whether AI uses or wastes all that water. As far as I’m concerned, that question has already been answered in the negative by Masley and others.1 Instead, I will explore an important question that emerges from the premise that the water issue is, in Masley’s words, “a non-issue”: Why water?

Why is the anti-AI crowd fixated on water specifically? There are plenty of defensible reasons to criticize AI as a technology and as an industry (I’m pro-AI in terms of personal use, generative or otherwise, but I won’t hesitate to call out the companies or their leaders and have done so many times in the past), but the available evidence strongly suggests water is not one of them.

Here’s my take, which I will elaborate on at length here (I encourage you to take a look at the footnotes): the water issue isn’t so much an environmental concern that happens to serve a psychological need, but the opposite: a psychological phenomenon wearing the costume of environmental concern.

The reason why people won’t let it go is not empirical and has never been: no amount of evidence will stop them from repeating the same talking points over and over. This immunity to facts isn’t incidental but the key to understanding what’s actually happening (more on this in section V). But there's more: we have to look into the economics of moral status competition, the cognitive efficiency of simple narratives, and the human need for certainty in an uncertain world.2

Masley’s work is fundamental to demystifying the hyperbolized caricature that the water issue has been made out to be by the media and to figure out the truth, but it’s ultimately hopeless to change people’s minds.3

II. The safest bet possible

I’ve heard about the water issue from friends and acquaintances who know virtually nothing else about AI: “Hey, so it’s true that ChatGPT wastes lots of water? Might stop using it then…” The degree of cultural penetration of this particular opinion, manufactured into a handy, memetic factoid, seemed to me genuinely dumbfounding:

Why are so many people (who are otherwise uninterested in AI beyond its immediate utility) suddenly concerned with water?

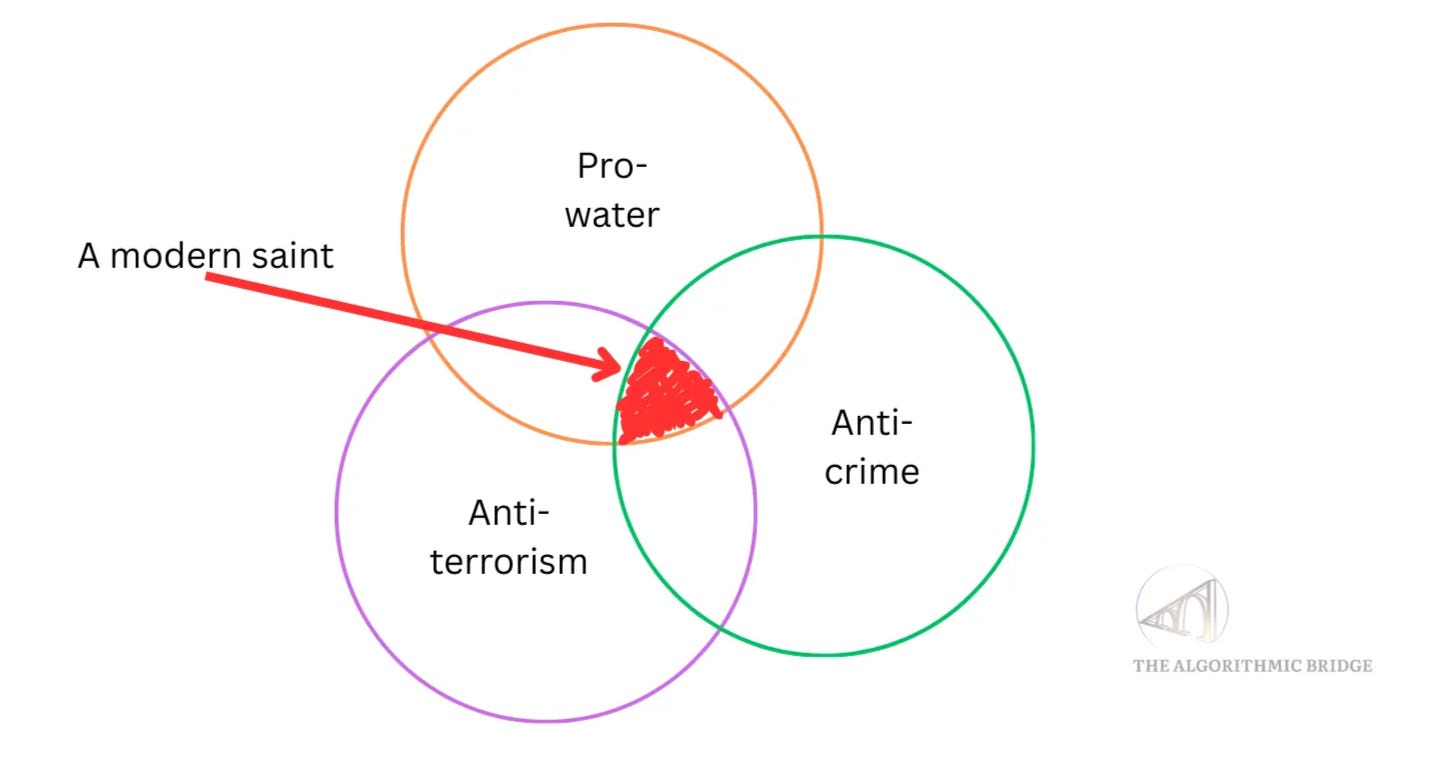

I couldn’t stop thinking about this question. Anecdotally, the provenance of the critique didn’t seem to be proportional to the level of knowledge or the willingness to accept that the tools are useful. So I started to investigate and concluded that the first piece of the puzzle is akin to what political scientists call a valence issue. A valence issue is a condition universally liked or disliked by the entire electorate: a safe bet.

Typical examples: everyone hates crime, everyone loves clean, abundant water, and everyone despises terrorism. There’s no #terroristslivesmatter slogan. There is no pro-drought lobby, no anti-anti-crime political party. (Whatever happens behind the scenes is another matter.) This universal valuation creates the safest possible bet in the circle of things one can defend, which, conversely—if we inverse the valence—also creates the safest possible bet in the circle of things one can criticize: if you waste clean water, creating in turn artificial scarcity of the most basic (controllable) resource in the universe, you are setting yourself up to be labelled as the most hateful person ever to exist.4

Water is important across every culture, every ideology, every value system that has ever existed, the reason being straightforward: as carbon-based life, humans insist on their water dependence. When they criticize “wasteful corporations” in terms of water usage, they’re not expected to defend nuanced tradeoffs or grapple with competing values; they’re aligning themselves with something so incontrovertibly good that disagreement is inherently inhuman: they either gather allies to the cause or expose heartless monsters. It’s a win-win situation.5

Such unconditional moral safety is itself deeply appealing to people who need to feel certain about their positions: when they tie their identity to the idea of a perfect moral being, they can’t afford to catch themselves entangled in ambiguous moral issues. If they somehow end up on the wrong side of history, they have to deal with 1) the social shame of being immoral and 2) the guilt of seeing their identity invalidated by their own behavior. Compare this to other potential criticisms of AI. Attack it based on copyright law, and they risk a debate about fair use. Attack it based on economics, and they risk a debate about productivity and job creation, and the effectiveness of a universal basic income. Those are muddy battlegrounds.

But once they declare that AI wastes clean water, they’ve pre-won the argument. This bypasses logic entirely and triggers a primal survival anxiety in the audience. They get to feel like rebellious revolutionaries speaking truth to power while actually taking the most conformist stance possible. One that, in practice, will achieve nothing because the water issue is not such.

To be clear (this is a controversial topic that requires careful handling), I’m not saying ethicists and skeptics chicken out of those other, more arguable issues; they have valuable concerns and express them often. I’m saying that the ubiquity of the water issue is proportional to the safety of the bet, as is the number of people who choose to speak up on it, despite it being false.

You can support my work by sharing or subscribing here

III. The new moral economy

The safety of the water critique is only part of the story. We need to understand the economic context in which this criticism operates.

In certain progressive subcultures, traditional markers of status and achievement have become ideologically compromised.

Wealth accumulation is suspect, associated with exploitation and inequality (the degree to which one wants to make more money is proportional to how evil one is willing to be).

Professional success can be tainted by complicity in capitalist or extractive systems (instead of thinking that the current meritocratic system is deeply flawed, they choose to believe that a perfect one is undesirable).

Even artistic or intellectual merit carries the whiff of elitism (entertainment is art; reading the classic books of literature is gatekeeping; there are no experts).

When they’ve rendered most conventional forms of distinction morally problematic, what remains?6 Moral purity itself becomes the currency. The ability to identify and condemn moral failures in others, to position oneself as more aware and more aligned with correct values, becomes one of the few remaining avenues for social competition and self-affirmation.

This creates what we might call a moral entrepreneurship economy—the second piece of this psychological puzzle—which, like any market, rewards efficiency. (Isn’t it ironic that despite trying to escape the forces that govern our society, they still end up immersed in a game that obeys the same dynamics? God is funny.)

So, besides being safe, the water critique of AI is remarkably efficient along multiple dimensions. First, it requires no expertise. They don’t need to understand AI models, transformers, training runs, inference costs, or the economics of compute. They don’t have to grapple with the complexities of balancing progress against environmental impact (which is, in my opinion, a more interesting and urgent conversation to have: not so much “AI is bad” as “How do we ensure the transition proceeds in the best way?”). They don’t need to understand how the water cycle works, or the network of canals, or a hydraulic press. They just need to know that AI uses some amount of water, and that water is precious, and the trick will be set.

Actually, they just need to believe that AI uses more water than it should, which is an easier case to make because they can define “more water than it should” in arbitrary terms contingent on how much they already hate AI. This makes it democratically accessible as a form of criticism and one perfectly aligned with how they already feel!7

To feel superior to the engineers, the builders, and the executives who have the money and the power (who are criticizable for other reasons), the critic must frame them not only as greedy but as morally bankrupt. The water argument is perfect for this because it frames the tech industry as parasitic, extractive, and exploitative (this is a spectrum, it’s not “yes” or “no”). This paints the AI ecosystem as a vampire, literally sucking the lifeblood out of the local communities to fuel its digital fantasies.

Such a delicious reversal of status, right? In the real world, engineers build the future (yes, they do, I find it mindblowing that I feel this needs to be stated twice). In the moral fantasy world of the water issue flagger, the engineer is essentially a criminal or at least complicit, and they are the Defender of the Earth. The subtext is clear: I may not be successful or powerful or smart, but at least I am not evil.

IV. A concrete, visceral trap

The efficiency of water as a symbol operates on yet another level, one rooted in how human cognition processes types of information.

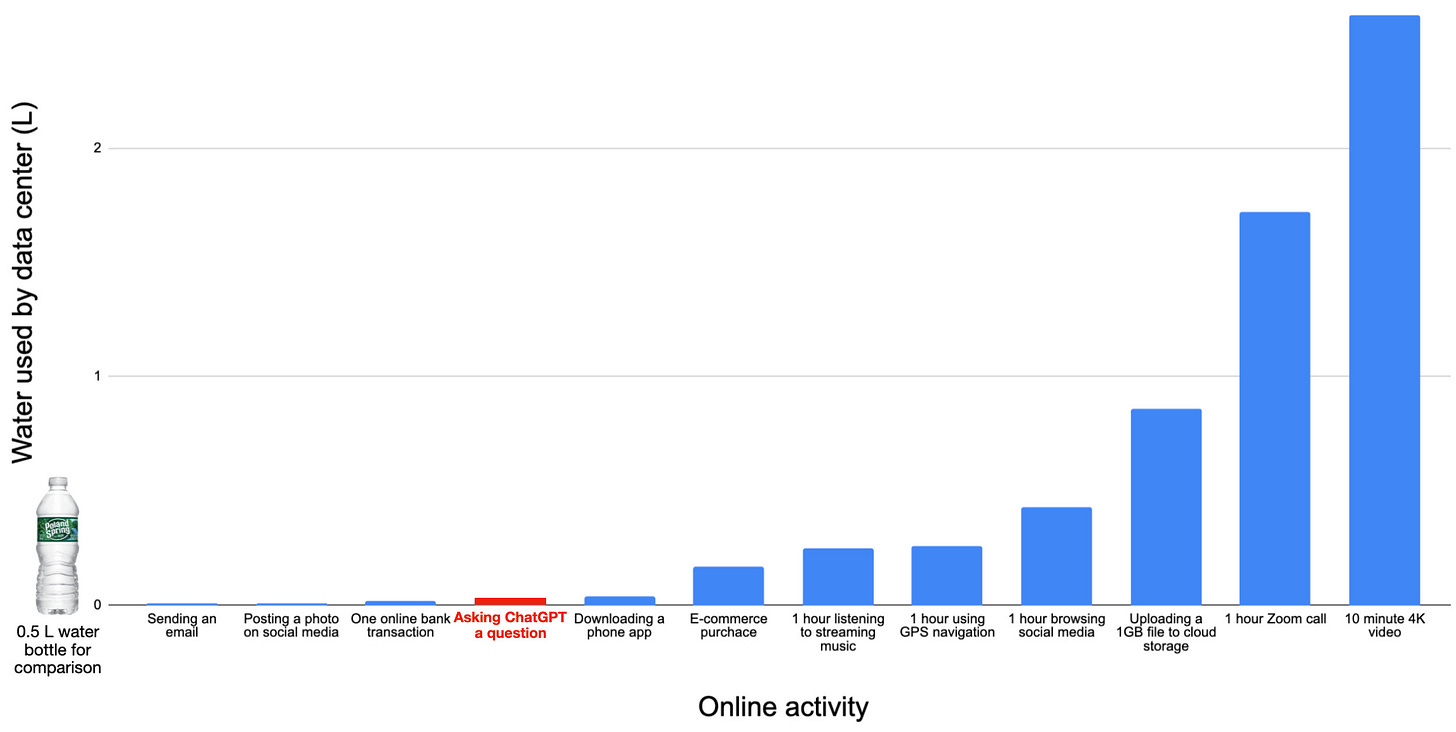

Water is far from the only discursive weapon wielded against AI. It is often accompanied by energy or power, or electricity. However, people increasingly focus just on water, despite other things being a bigger deal (and still not as big as they’re made out to be either). Even merely putting them together in the same sentence—”AI wastes a lot of water and energy, how can you use it!?”—is a transgression of the actual orders of magnitude.

The water critique satisfies what psychologists call the concreteness bias, the third piece of our puzzle.

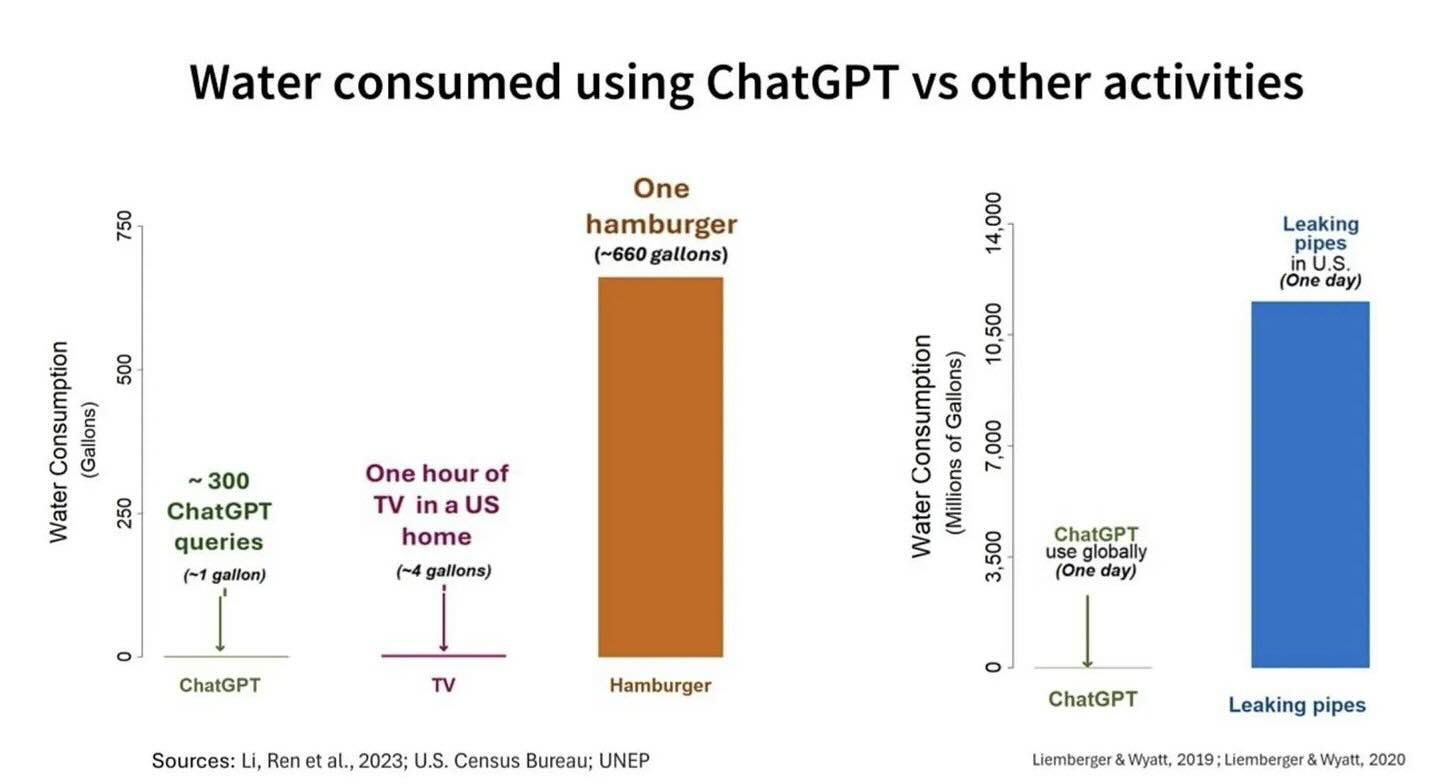

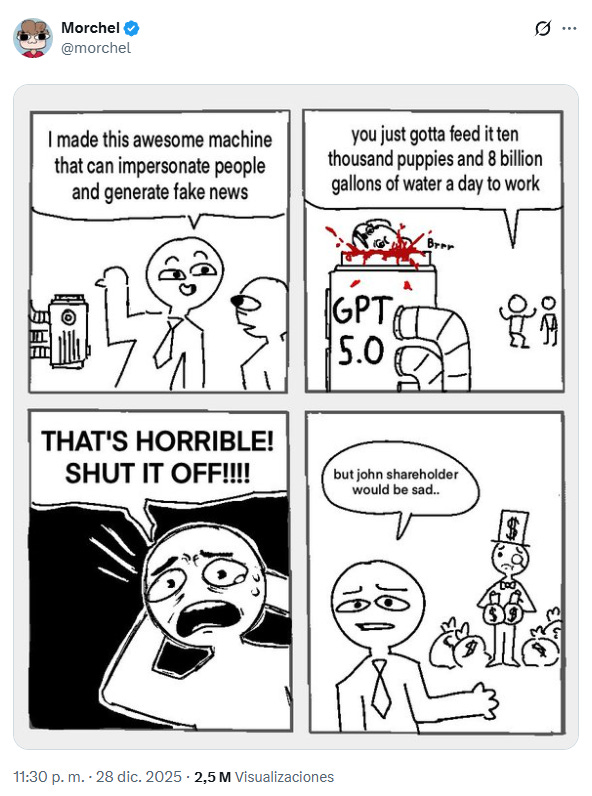

Human brains are not well-designed for weighing abstract probabilistic benefits against concrete present costs. Many of the potential benefits of AI—advances in drug discovery, better climate modeling, safer roads, productivity gains—are distant, uncertain, and often overwrought. Water being consumed is concrete, present, and visceral. You can picture it. You can draw it and exaggerate it for comedic purposes. You can imagine the “8 billion gallons of water a day” flowing through pipes and evaporating into the atmosphere. The cemetery is full of great, abstract arguments.8

The psychology of the visceral and the concrete fixes water as a powerful symbol. Labor is abstract. Intellectual property is abstract. Electricity is abstract. You cannot hold a kilowatt in your hand. It’s invisible magic. But water is life. We drink it, we are made of it.

This makes any apparent water-related catastrophe—”Google is leaving small Latin American towns thirsty”—touching in a way that “CHIEF achieved nearly 94 percent accuracy in cancer detection,“ or “a single 16-day [AIGFS’s weather] forecast uses only 0.3% of the computing resources of the operational GFS and finishes in approximately 40 minutes,” or “A generative–AI-designed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) drug progressed from target discovery to phase I in 18 months [vs traditional 4-5 years],” or “Waymo ADS significantly outperformed . . . the overall driving population (88% reduction in property damage claims, 92% in bodily injury claims)” cannot match.

Those things are measurable, yes, but the brain doesn’t compute them except in hindsight after mortality due to diseases or accidents decreases over time (but then it’s yet an extra effort to trace back such “miracles” to the causes). People internalize a dangerous bias: they are ungrateful toward things that matter a lot and unnecessarily aggressive toward things that matter little.

This taps into what we might call the zero-sum fallacy (or zero-sum thinking), the fourth piece of our puzzle, which can be summarized by this: what you gain, I lose.

The critic intuitively believes—or chooses to believe—that if a data center uses a gallon of water, that is a gallon of water stolen directly from a thirsty person. This is economically and hydrologically illiterate, but it doesn’t matter because this is how they elevate the water issue into the utmost moral wrongdoing: you are not only exploiting the Earth but especially the poor. Industrial water cycles, gray water usage, and local watershed management are complex, but your typical critic is not interested in complexity; it might bury the lede, it might confuse the audience, it might, God forbid, add nuance to the perfect hook or meme.

They are interested in the symbolic threat: AI is the villain in a Disney movie, hoarding the water while the villagers go thirsty. The cognitive load of forming an opinion is trivial when you can map the entire situation onto a pre-existing moral template.

V. The immunity to facts and data

We’ve now traced why the water critique is appealing: it’s safe, efficient in the moral economy, and viscerally compelling in an economy that is assumed to be zero-sum.

But all of that would be irrelevant if AI companies did actually waste a lot of water on serving slop machines; the psychological motivations of an argument, however twisted, matter little if the argument is sound. But why does the water issue persist in the face of overwhelming contrary evidence? To understand that persistence, we need to examine people’s immunity to facts (which is another way of saying that people believe what they want to believe).

I think it’s fair, when surrounded by ambiguous evidence, to play the safe card or use rhetorical tricks to incite visceral reactions (reproachable, maybe, but not plain wrong). It’s also fair to simply believe the wrong thing because you’ve been shown the wrong information and didn’t bother to look further. But when the facts have been laid out, and it’s a matter of looking for them (and then counter-evidence and so on until you find the primary sources), you have to add another piece of the puzzle to the analysis: an active willingness to avoid being involuntarily exposed to a truth you can’t or don’t want to accept. The immunity to facts is thus driven by psychological preconceptions (what you believe) and needs (safety, moral superiority, an enemy, etc.), but also by an unwillingness to put truth before preference.9

Rigorous and data-backed debunking exists but is indeed scarce. Masley and a few others that I can count with the fingers of one hand are alone against the entire conglomerate of mass media and shameless influencers, who know that right now there are more potential clicks in criticizing the AI industry for whatever reason (correct or not) than in debunking the extremely popular water issue (I try to weigh this fact in my coverage; I won’t deny getting clicks is part of my job, but will not make easily clickable claims if I think they’re untrue). I understand it’s hard to care about truth when the internet is full of noise and distraction, and social media doesn’t incentivize civil debate, but articles like Masley’s are publicly accessible for free, so the responsibility is on your shoulders.

However, this scarcity doesn’t imply unpopularity: Masley and others have come up with analogies and metaphors, and comparisons (shown below) that lend themselves to virality as much as “a datacenter is worse than a drought.”

And yet, when the water-fixated critic hears that water usage is dwarfed by agriculture, by thermoelectric power generation, by golf courses and decorative lawns, by watching Netflix or eating hamburgers, the critique doesn’t disappear. When they learn that many data centers use recycled or non-potable water or that they simply evaporate the water or return it to local supplies, or that the figures being cited are wildly inflated, as happened in Hao’s case, the concern doesn’t decrease proportionally.

This phenomenon points to the fundamental reason why I’m writing this, for which I’ve already provided explanatory psychological mechanisms: the water issue is not about water, whether or not there are viral-worthy counter-facts.

The person expressing concern about water is not waiting for better data to update their position as a Bayesian rationalist would (I hope people working so hard against the current, like Masley, don’t expect otherwise). They can’t afford to let data topple an entire edifice of convenient beliefs. The criticism serves a non-negotiable social function: it protects their identity, signals group membership, shows moral awareness, and establishes status within the community. These functions persist regardless of the empirical reality of water consumption, however well exposed, however widely available, however cleverly analogized.

We are, after all, not clever humans who happen to be social but social animals who happen to be clever.

The concreteness bias that makes water emotionally compelling in the first place also explains why abstract data can’t dislodge the concern once established. You cannot debunk a visceral feeling with facts, and you certainly cannot debunk a religious conviction. That’s where populism finds a gap to emerge. In the words of Joseph Heath (Populism fast and slow):

What is noteworthy about populists is that they do not champion all of the interests of the people, but instead focus on the specific issues where there is the greatest divergence between common sense and elite opinion, in order to champion the views of the people on these issues.

I could finish this post here. We have already gained deep knowledge about the psychology of people criticizing the water non-issue, and a reasonable multi-causal explanation about the fundamental question I wanted to answer: “Why water?”

I invite those of you who want to follow me a bit deeper, into what is probably the most speculative section, to keep on reading (also, footnotes). It is about god, but what, in life, is not ultimately about god?

VI. Gaining points before God

The quasi-religious fervor of the water critique requires that moral capital functions also as spiritual currency. God might be dead, but we’re constantly conjuring new ones up.

We are witnessing the rise of what might be called eco-theology. As traditional religious observance collapses among these demographics, political and environmental activism rushes in to fill the “god-shaped hole” (again, these demographics find themselves governed by forces they often claim to despise or straight up reject, like religiosity and theism and market pressures). In this new theology, the mere act of being human, of consuming energy and resources, generates guilt in the form of a “carbon footprint.”

AI and its enablers must be punished for their evilness, they think. Criticizing AI’s water usage is thus a form of public prayer. When they post an infographic—or a meme, it’s often just a dumb, wrong meme—about how much water ChatGPT consumes, they are not so much engaging in activism as ritual purification: “I might be a human, but I’m from another species than them.” The extent to which this is performative rather than genuine is unknown and mostly irrelevant. To me, it looks less like gaining social media points for clout or whatever than gaining points before god, a secular, eco-theological god.

Interestingly, and counter-intuitively, the need being satisfied isn’t primarily about external validation from peers, as I said above, though that’s an important part of it, but about internal validation, about being able to see yourself as a good person, as someone on the right side of things.

If AI is just a tool that uses resources like any other industry instead of a greater offense against the pantheon, then their rage is unjustified insofar as they don’t oppose with the same intensity all those other industries and reject any relation with them (which is a fair position, but in practice impossible if one wants to belong to society). As I wrote recently: “Criticizing AI is valid, but hypocrisy is high: we only care about the carbon footprint of technologies we don’t personally enjoy yet or for which we hold a grudge.” If they frame AI as a particularly insidious demon draining the world’s aquifers, however, then their rage is righteous.

Anyway, because I can’t go higher than god or deeper than demons, I think we can leave the topic here. My primary goal was not to convince you that the AI industry wastes no water—Masley did that for me—but to convince you not to try to convince those who still insist that the AI industry wastes way too much water that it actually doesn’t. Given what I’ve exposed here, that would be, to stick to the theme, like pushing water uphill or, as us Spaniards say, like drawing a line on the water.

You can support my work by sharing or subscribing here

Including Hao. She may have missed the mark on that figure, but the rest of the data is, as far as I can tell, correct. The remaining differences between them, it’s fair to assume, are a matter of perspective and preferences; you can check the sources yourself and decide whether you believe AI companies should stop training AI altogether or if the issue is not that big of a deal after all.

To contextualize the epistemic value of his post: It is, at most, worth an appendix next to the extremely thorough and important work that Masley and others have done in terms of digging out the facts and the empirical evidence about AI and water. Again, I include Hao in that group; she has been, time and again, an important voice holding the AI industry in general and OpenAI in particular accountable. The industry might not be wasting that much water, but they’re doing other things wrong, and I’m sure, although this is a personal value judgment, that they would indeed waste all the water in the world if they had to to run their multi-billionaire operation. I name both Masley and Hao in this footnote because I want to preemptively kill any attempt to categorize this post into the “us vs them” moral battle that’s taking place; I’m sorry but I won’t give anyone that easy way out of exercising one’s critical thinking as a citizen of society interested in AI: the world is too complex to allow such simplistic dichotomies. As I wrote in the main text, “these two facts can be right at the same time: 1) the AI industry has done some reproachable things, 2) wasting water is not one of them.”

I think there’s a fundamental misalignment between what Masley’s work can achieve, e.g., influence policy, and what it ought to be able to achieve in a perfect world, e.g., convince people this is a non-issue, but it’s also not the intention of this post to give his arguments a rhetorical spin so that people listen.

Something like this happened when, legalities aside, pharma investor guy Martin Shkreli’s company, Turing Pharmaceuticals, obtained “the manufacturing license for the antiparasitic drug Daraprim and raised its price to insurance companies from $13.50 to $750.00 (USD) per pill,” per Wikipedia. He was called “the most hated man in America” at the time.

Note that neither Masley nor I is denying the fact that water is valuable—it’s not so easy to find heartless monsters, actually—merely that the AI water issue is not such; if it were, then virtually everyone would be on board against the few billionaires benefitting more from wasting water on AI slop (not even they’re monsters most of the time, just successfully greedy and selfish). That he decided to investigate the water thing is doubly virtuous in my eyes: 1) he chose to reject some easy moral or social points and instead set himself up to be attacked for 2) seeking and unveiling the truth.

The system pushing a growing fraction of people out of itself is the system’s responsibility; so even though I’m explaining the psychological drivers behind the popularity of the water issue, I don’t intend to make the case in favor of only holding people accountable of being knowledgeable and truthful: when the system is doing its best to locking us out of the standard ladders of status and value it should be called out in stronger terms given its stronger determination and power and I’ve done so plenty of other times.

I disliked that Hao corrected the 1000x mistake without changing the wording regarding how the numbers should be interpreted. This was the original controversial sentence: “In other words, the data center could use more than one thousand times the amount of water consumed by the entire population of Cerrillos, roughly eighty-eight thousand residents, over the course of a year.” She corrected it to this: “In other words, the data center could use more water than the entire population of Cerrillos, roughly eighty-eight thousand residents, over the course of a year.” It is factually correct but tonally similar despite implying a 1000x reduction in water use by the datacenter. With this, I mean that her argument is intact regarding her sentiment toward the AI industry. Compare that to what Masley considers “the correct description” (he doesn’t possess the absolute truth on this topic, just check for yourself): “A municipal water system serves 650,000 people. If a data center is built in the region, it would raise the system’s annual demand by 3%, equivalent to the water used by 19,500 residents.” Masley notes that Hao uses the “maximum permitted” water amount figure, whereas the actual figure has been as low as 20% in comparable Google datacenters. Hao chose not to correct this part.

This is the core argument I put forward two years ago in Here’s Why People Will Never Care About AI Risk, where I suggested that people can’t afford to care about extinction risks coming from AI, whether imaginary or not, because the cognitive cost—out of abstractness rather than difficulty—is too heavy.

It’s pretty much impossible for most people in most situations to access capital-T Truth. However, I consider truth to be a spectrum: you are not either in possession of it or not; you are instead closer to it or further away from it. Being closer is better. If you have access to new evidence that can draw you closer to the Truth, even against your priors, you should update and then reconfigure your identity, psychological needs, and so on. One should never sacrifice truth in favor of convenience.

I’ve noticed this water narrative coming up in many other unrelated stories. When the protests against the Keystone XL pipeline were at their height, it was actually water that was the focal issue rather than oil itself. (The slogan of the Standing Rock protests was “water is life”.)

At around that time, I had noticed that Nestle was becoming one of the most hated companies on Reddit, because of various facilities to bottle water. People got extremely upset at one facility in Michigan, where there is nothing like a water shortage, because it somehow seemed insensitive to bottle water in Michigan at a time when the Flint water infrastructure was leaking lead. People didn’t quite understand that the issue was lead - they somehow thought Flint had a water shortage, and assumed Nestle was somehow making it worse.

This issue has driven me nuts since it first went through. The bigger mistake is that they mistook 'flow' for 'consumption.' Most water flows through a cooling system at a rate, say 100 gallons a minute. Therefore, if you asked ChatGPT 1,000 question a minute they said each question 'consumed' 1/10th of a gallon. But it's not like drinking water and pissing it out, it flows back to the holding system, cools, and cycles back. The evaporation is something they want to avoid because water isn't cheap. The biggest mistake they made was equating flow with consumption.