They Are Sacrificing the Economy on the Altar of a Machine God

The AI bubble is about to pop

I.

Technological bubbles are misunderstood. If you asked any person on the street for a concise definition, you may get something like this: “A bubble happens when excitement and speculation push tech company valuations far beyond their real economic value; eventually reality catches up and the bubble bursts.” Maybe not any person on the street, but anyway, to the extent that it is a simplification, the description is accurate.

The problem comes when we over-interpret the unspoken implications: A bubble, it is often believed, spawns out of thin air; there’s nothing of value hiding inside but a void made out of lies and vaporware waiting to fall upon the world like a heavy rain. But that’s rarely the case. Bubbles are simply an unhealthy extension of the real value lying at the center. There is a “kernel of truth,” as OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, the modern “Bubble Man” per excellence, told The Verge.

Investors buy (belief) and then buy (money) that kernel of truth—out of a common greed but also out of an unusual sensibility toward optimistic types—and redirect the flow of money until it floods the sector and the bubble implodes, killing most of them in the process, but preparing the soil so the few winners can thrive in the subsequent period of blooming progress and tangible value. That happened with canals, then railways, then domains. If history books are to be trusted—AI bros like to believe they’re millenarians, predestined to live during a singular time, but the odds are not in their favor—it will happen again.

So, is there an AI bubble? Yes, I think so. Altman himself acknowledges this PR-unfriendly possibility. (He says broader investment in AI and semiconductors is based on fundamentals and thus not creating a bubble, but that “speculative capital” is growing; so, not OpenAI but those others? Yeah, maybe.) The more important question is: are we getting nothing out of it? Not really. We will get a new normality.

However—and this why I decided in favor of that bait title that made you click—a couple of big reasons imply this bubble could be worse than the others you studied in high school in terms of both destructive power and ineffective recovery.

II.

But first, now that we have gathered for this private meeting, let me defend a position antithetical to the kind I'd usually share in public: bubbles are the collective by-product of individually good intentions. In a way, bubbles are an inevitable and welcome interstitial phase between selfish short-termism and long-term progress.

To dig into this, I’ll borrow the ideas of Mills Baker, head of design at Substack. He wrote a great post whose conclusion can be fairly summarized with the subtitle: “[W]e should be more optimistic and even tolerate excesses of optimism in Silicon Valley (while still roasting Pollyannas whenever it's fun).”

The argument goes like this (Baker will have to forgive me for such flagrant dumbing-down): hype is acceptable under the premise that only an optimist character, the kind prone to exaggeration and hyperbole, can build the new world for which a bubble is only the inception point; its Big Bang. The cynical, pessimistic character (labelled by some as “realist,” depending on how intimately you identify with it) is a useful counterbalance to excessive optimism insofar as that optimism exists in the first place; otherwise, it’s dead weight. While optimism is an active force of creation, pessimism is a reactive force of modulation. I liked his last two paragraphs especially:

Each is called for in particular moments, and balanced, they can both contribute to the development of knowledge and the creation of successful enterprises of any kind. And this kind of creation is more valuable than “never looking foolish” or “never seeming too critical” or anything of the sort. Behavior, not identity, is what matters for collective endeavors; output, not inner essence, should be the focus of a professional working towards ends in the real world.

If optimists incidentally generate moronic hype-cycles, and if pessimists seem more concerned with looking cool than doing anything worth a damn, these are just the unfortunate by-products of an eternal tension none of us can claim to have cleanly resolved, and one which we probably shouldn’t hope to.

I agree. As I wrote, quoting his introduction (he cited me, so I return the gesture):

The problem comes, and this is the first reason why this bubble might be worse than usual, when the equilibrium between optimism and pessimism is broken; when those “moronic hype-cycles” spiral into such gargantuan monsters of delusion and detachment (“we will build the machine God”) that they cover the lightcone of crazy predictions, overshadow any cynical attempt at balancing them out, and prematurely kill any eventual success by ensuring it falls short of expectations. Bubbles build the world, but they destroy it first. And so bubble men like Altman, in their typical optimistic demeanor, push forward, hoping the destruction is not too bad; if the fallout is so devastating that no fertile ground remains on which to erect the edifice of modernity, any person on the street could tell you it was not worth it.

Do we have evidence to believe this bubble is risking such a terrible scenario? Let’s find out. Writer Freddie deBoer, a well-known critic of the millenarian sentiment among AI evangelists but not a tech expert himself, responded to my response to Baker above: “At present the world economy is being propped up by the LLM bubble to a degree that's truly frightening.”

III.

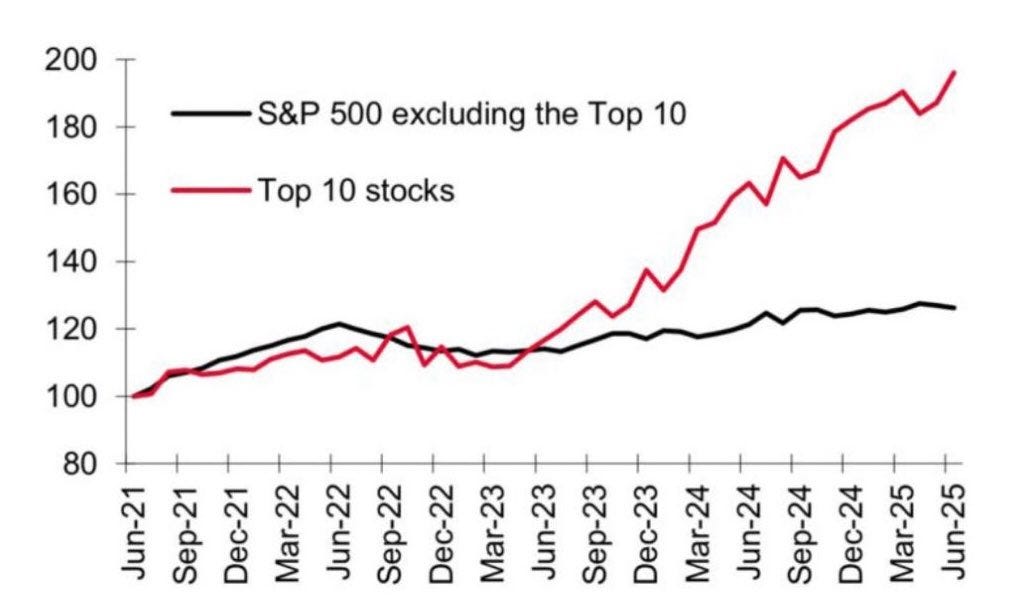

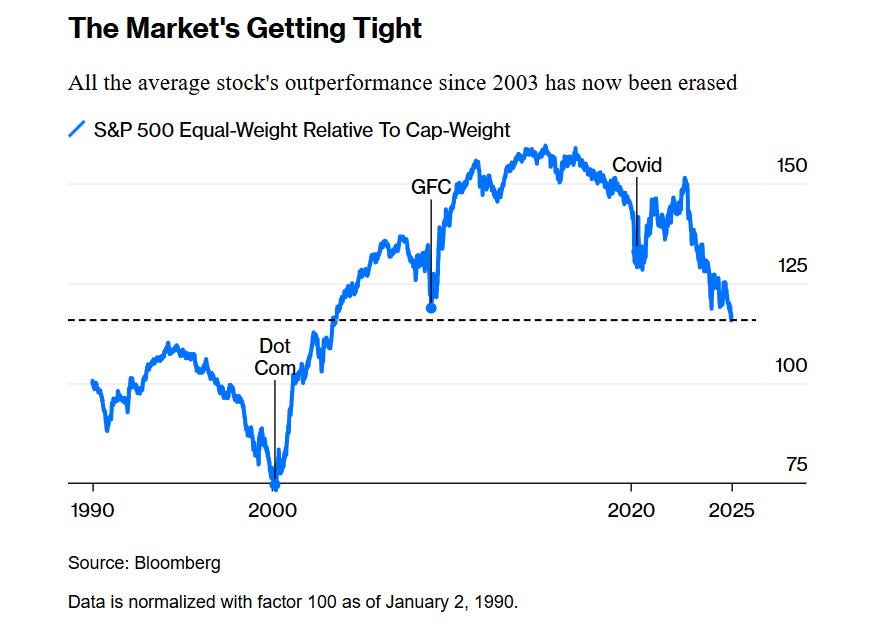

Let’s take a look at the numbers. Below is a chart of the S&P 10 vs. the S&P 490 (the top 10 publicly traded companies in the US vs. the next 490) between 2021 and 2025. Below that, I’ve added another chart by Bloomberg that normalizes all the stocks as weighing the same, so that you can see what the S&P 500 looks like if no outsized companies were concentrating most of the value. What do you see? (Remember that ChatGPT was released on November 30, 2022.)

At first glance, that ugly divergence in the first chart and the uglier downward slope in the second suggest deBoer is correct—something’s off with the US’s economy.

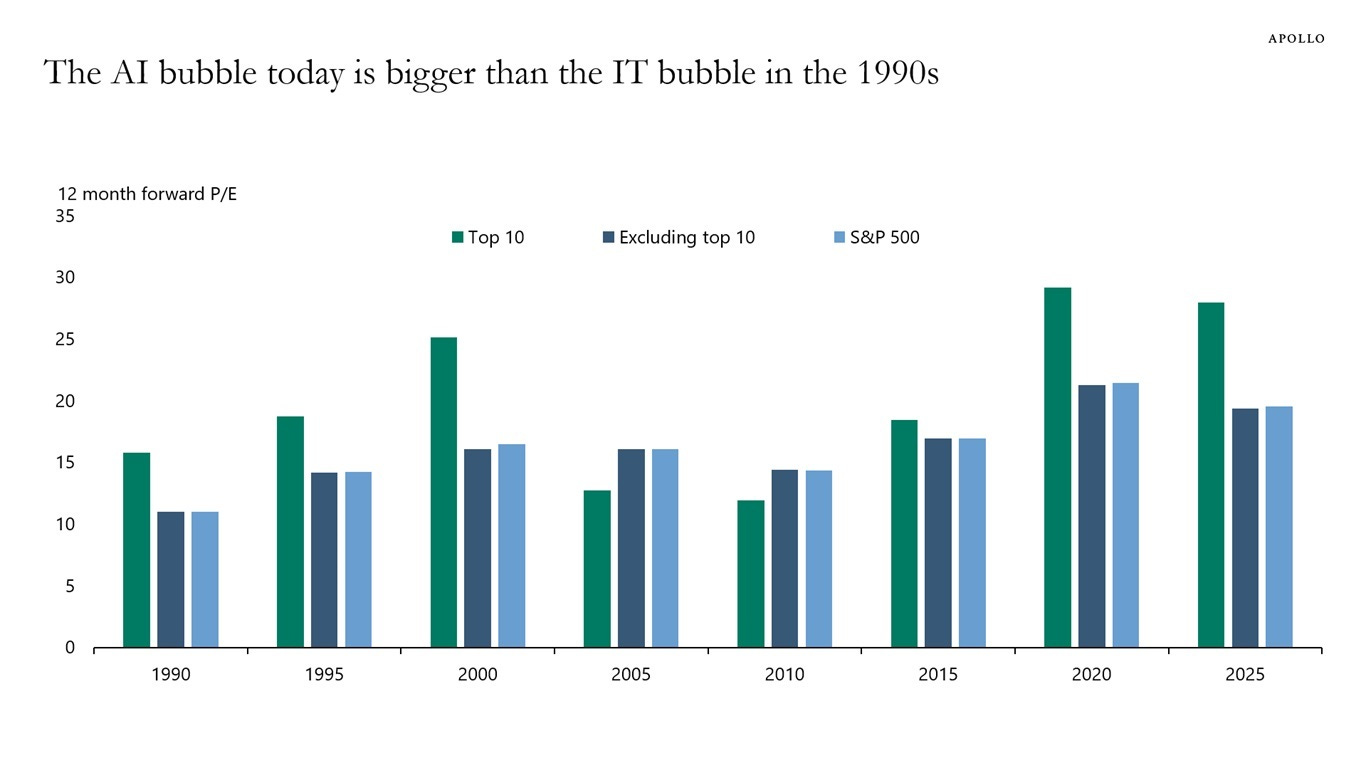

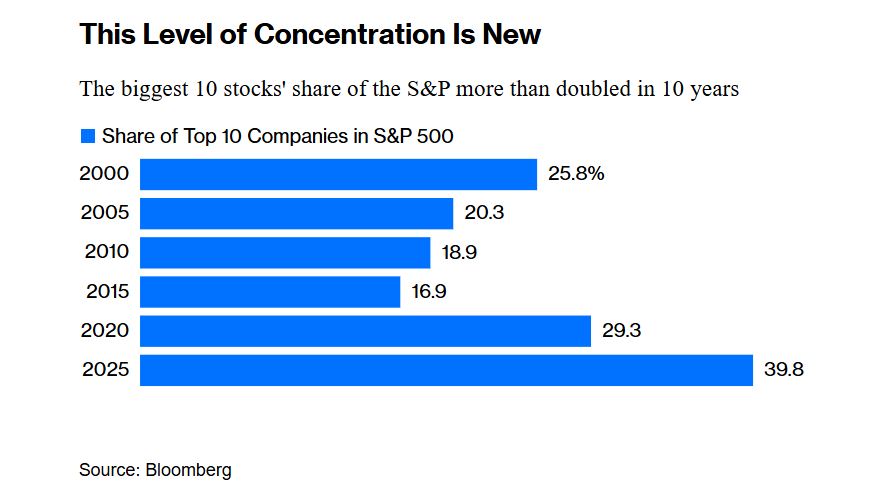

Economist Michael A. Arouet, who shared the first chart on Twitter, says this: “S&P 490 has had basically no earnings growth since 2022, despite rampant inflation. It’s just 10 companies doing really well, while the broader economy is in contraction in real terms.” Torsten Sløk, chief economist at Apollo, says that “The difference between the IT bubble in the 1990s and the AI bubble today is that the top 10 companies in the S&P 500 today are more overvalued than they were in the 1990s.”

Bloomberg’s take is in line with that: “It’s usual for a few winners to win big at any one time. . . . It’s unheard of for 2% of the index’s companies to account for virtually 40% of its value.” So the economy is not growing and the bubble is already bigger than it was in the 90s. Nice.

By the way, you know every one of those 10 companies (even those of you who aren’t from the US, like me). They are Big Tech and one well-known outlier (in descending order by market cap at the time of writing): Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple, Alphabet (appears twice), Amazon, Meta, Broadcom (semiconductor company, perhaps the least famous of them all), Berkshire Hathaway (outlier), and Tesla.

They are undergoing unprecedented growth, so let’s see what they’ve been up to recently in case they’re so well off—they seem to be growing in earnings as much as they’re growing in value!—that they can steer this battered ship to a safe harbor. Oh, but of course, they’ve been building datacenters (written like that, it feels like a vast understatement) to train and serve large language models like ChatGPT!

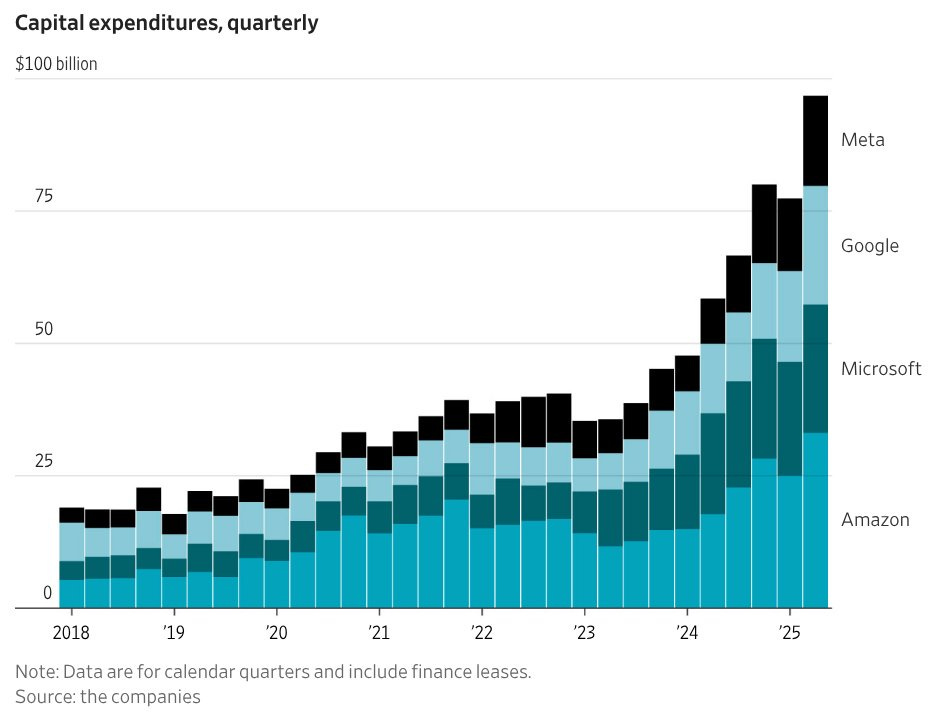

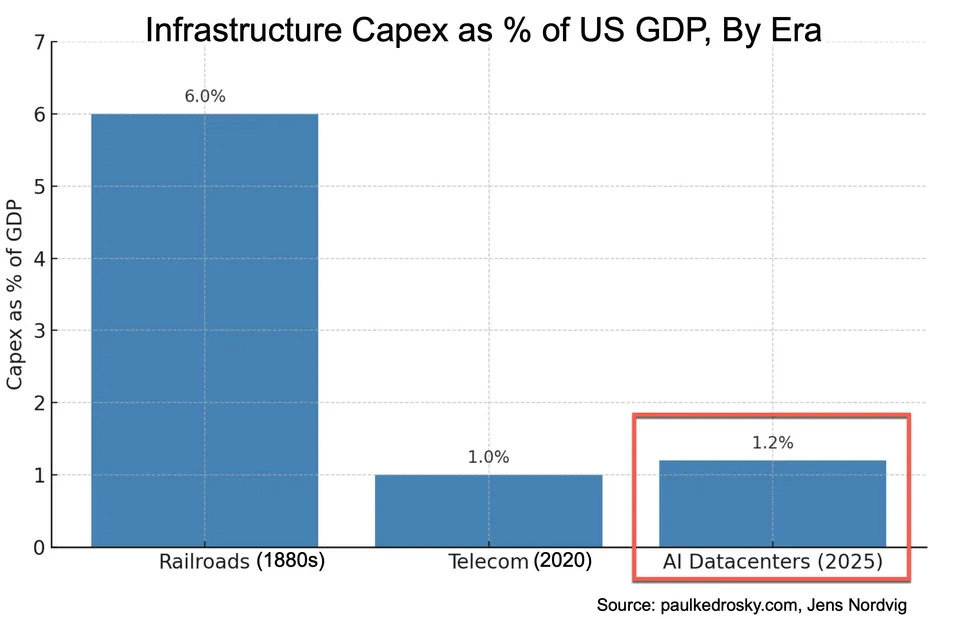

Wall Street Journal columnist Christopher Mims shared another chart, saying: “The 'magnificent 7' spent more than $100 billion on data centers and the like in the past three months alone.” Man, are they optimistic. Mims linked to an article by Paul Kedrosky, who offers another perspective on the AI bubble, as a percentage of GDP. Kedrosky, in turn, quoted Chinese President Xi Jinping, who warned of overinvesting in AI-focused datacenters. When Xi Jinping and Wall Street traders are on the same page, you know it’s bad.

So, back to deBoer’s insight, I think we can safely conclude that he is correct: a few top stocks are hoarding most of the value increase, and although their profits are growing accordingly, they’re putting it back into the economy in the form of AI-centered capital expenditures, which are yet to yield profits—

—or tangible value for consumers and businesses. That’s right. When Altman told Azeem Azhar of Exponentially in 2023 that AI was the missing innovation that could keep GDP growth sustainable, I don’t think he had this in mind. Two years later, Big Tech keeps erecting these barely manned giant buildings, which inflate total GDP numbers while concealing the lack of AI-related productivity gains that should be reflected in the GDP of the entire rest of the US economy.

Indeed, generative AI, as a general-purpose technology, won’t be making a dent in economic charts anytime soon if 95% of pilots are failing. Whether the reason is a “learning gap” on how to use the models, the natural delay between innovation and meaningful integration, an undefensible absence of reliability gains for complex or sensitive workflows, or simply that generative AI is not that useful, it doesn’t matter: when you hype an innovation so hard and so often, people expect the results to manifest by themselves. “Do I have to take a prompt engineering course? Fuck off, where’s my ‘magic intelligence in the sky’ that’s ‘too cheap to meter’?”

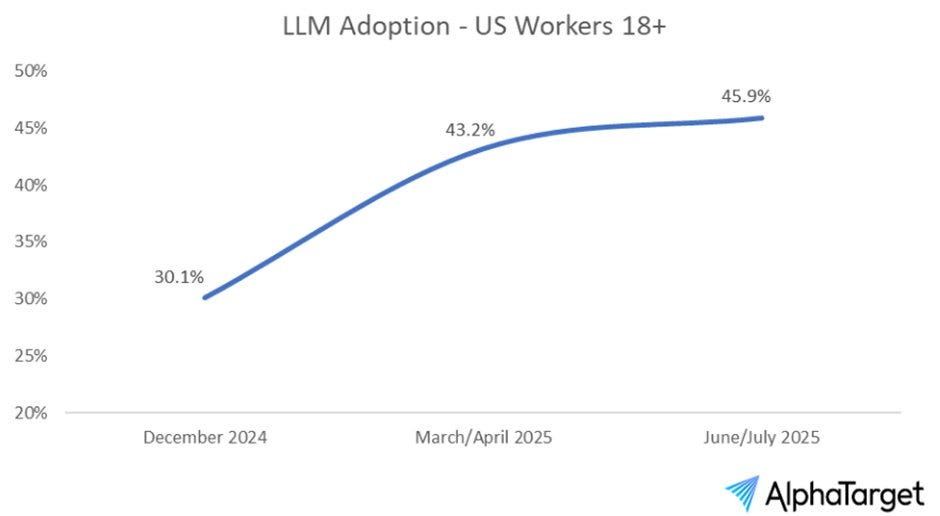

Oh, and since we’re on the topic of cheap intelligence, I should mention that the cost of serving new AI models (presumably more optimized) is no longer coming down on a per-token basis, which means companies have exhausted the engineering tricks they had up their sleeve to reduce OpEx (operational expenses). To finish this unapologetic display of killjoy-ness, user adoption is plateauing at <50% in the US.

Oof. What a bleak prospect. But that’s not all! That’s just the financial picture. If it were just from what I’ve written so far, I wouldn’t even be that alarmed, you see. What’s left is what scares me: money pulls strongly, but some things pull much more.