Why Silicon Valley Can't Afford Its Own Revolution

Follow the money

The central pillar of the generative AI narrative—the one psychological safety net that separates the current frenzy from the disastrous dot-com collapse of the 2000s—has always been the “Adults in the Room” theory.

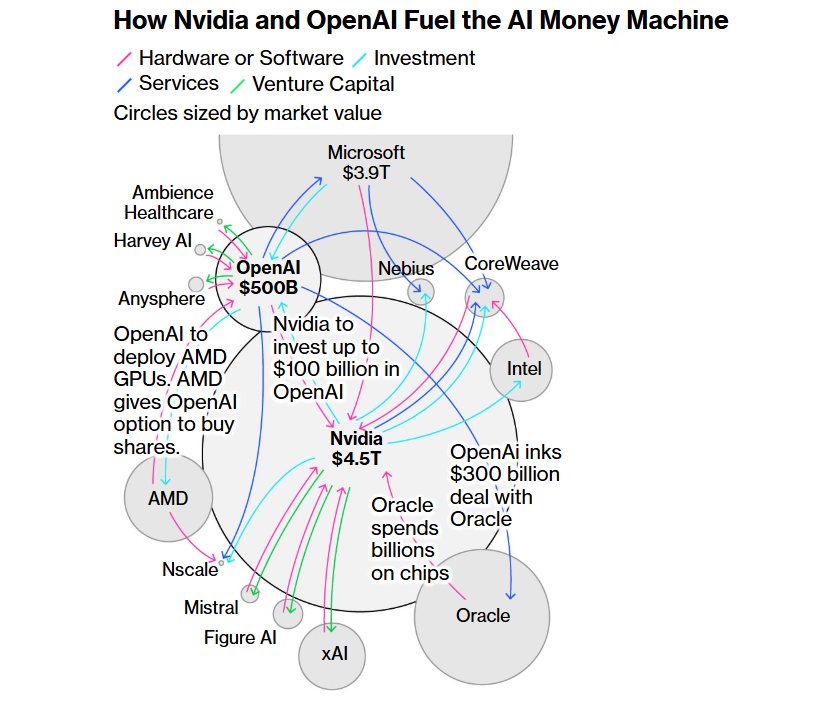

We are told that this time is different because the companies leading the charge are not fragile startups burning venture capital on pet food delivery websites. They are Nvidia, Google. Microsoft, Meta, and Amazon (not Apple), and, to the extent that the remaining leaders are, in fact, startups burning capital—as OpenAI and Anthropic are—they’re effectively protected by their deals with and acquisitions by Big Tech.

These are sovereign states disguised as corporations, sitting on cash reserves so deep—or so they say—that they could fund the entire revolution out of pocket change. We have been led to believe that their liquidity is a bottomless well, guaranteeing that the AI buildout will continue uninterrupted until the superintelligence arrives (or until it doesn’t, for it amounts to the same insofar as they get their return).

Even if there’s over-investing in AI infrastructure, even if AI doesn’t provide the short-term productivity gains that have been promised, even if… none of that really matters, they say, because, as of now, the revenue paying for all this is secured and independent from AI itself (AI-adjacent at most, as is the case with cloud platforms).

They can go on like this for a long time, they say. But if you take a closer look at the financial plumbing of Silicon Valley, you will see that this safety net is no longer such. The adults in the room are running out of allowance.

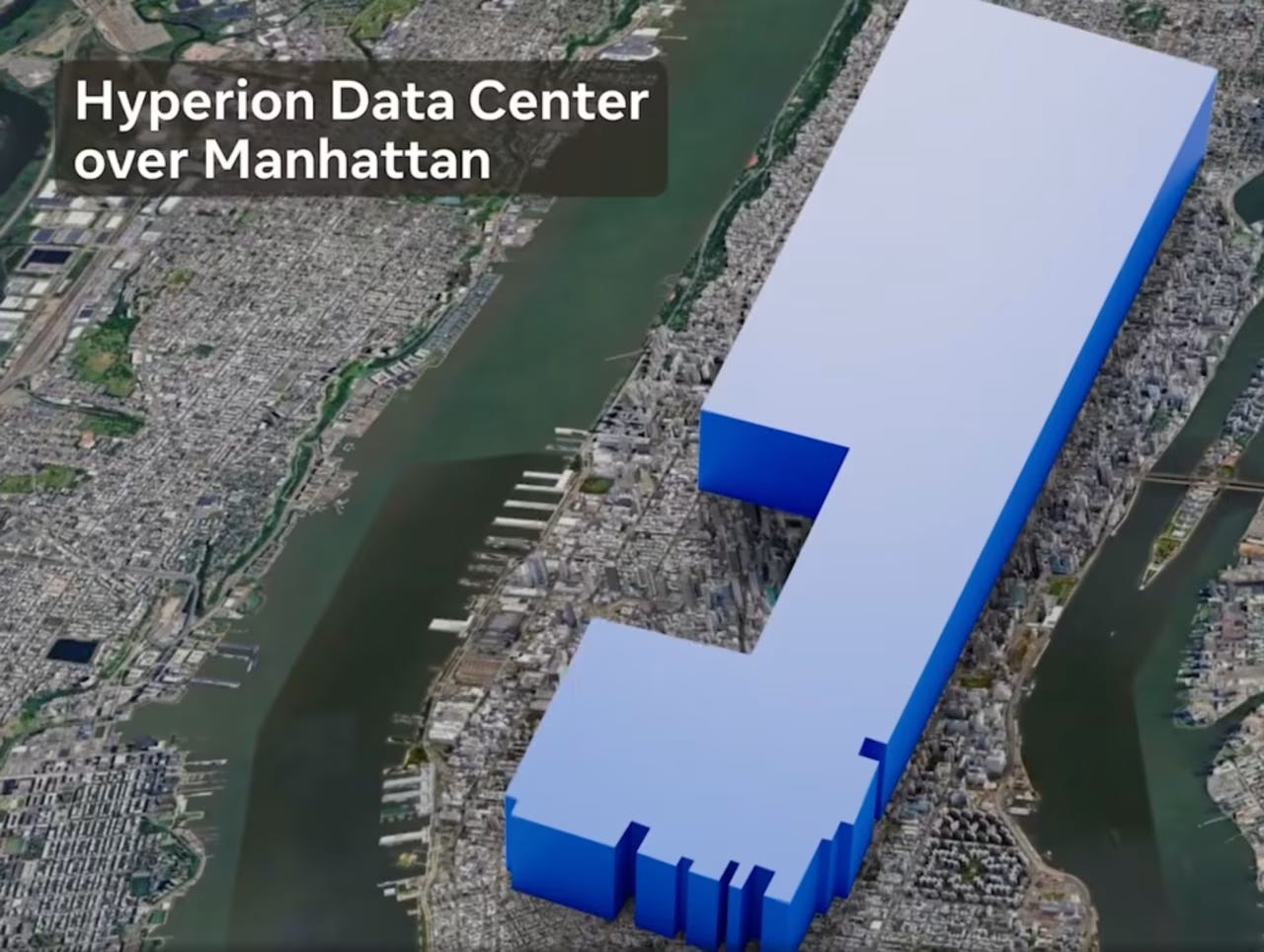

A recent report from the Wall Street Journal exposed a shift that should make even the greediest investor reconsider: For the first time in this cycle, the companies building datacenters can’t rely solely on their own internal profits to feed the insatiable hunger of this technology. The money—even for the most profitable companies in history, that is—is effectively drying up relative to the costs. Or, to be more precise, their liquid cash flow is no longer sufficient to cover the astronomical price tag of Nvidia H100 chips (soon B200 chips), copper, cooling systems, and land without putting their wider businesses at risk.

Perhaps the most important advantage Google has over the competition is having invested heavily early on in developing its own AI hardware, TPUs, to avoid incurring extra cost by paying for Nvidia chips to train its models. For instance, Gemini 3, the best model in the world, was 100% trained on Google’s custom chips (the benefits run even deeper than that).

But even its formidable stack or its comfortable position as leader don’t protect Google from other inescapable costs besides designing AI hardware; costs that are rising fast. What follows is a terrifying scenario that goes beyond the circular financing (bumping revenue numbers artificially) and even the AI bubble itself (which could be downstream from AI being less profitable than investors thought, who bought in out of fear rather than conviction). The consequences could reach the broader tech ecosystem and beyond. Capital allocators love to remind us that the winners build the world in the aftermath of a tech bubble, but only, I’d add, if the bubble does not, in fact, destroy the world.

To understand the degree to which this is terrifying, we need to understand the sheer scale of the spending. In the financial world, they look at Capital Expenditures (CapEx), which is basically money spent on physical things to build for the future (I’ve learned I shouldn’t just throw abbreviations around without explaining). According to a recent analysis by the Bank of America (per Axios), the “hyperscalers” (Amazon, Google, Microsoft) are on track to spend a striking “94% of operating cash flow (minus dividends and buybacks)” just to pay for this AI hardware (up from 76% in 2024). (This is a “consensus estimate,” meaning that larger, more stable companies are probably on the better half of the distribution, but still.)

In other words: Imagine you earn $5,000 a month (not bad, huh). You spend $2,000 on rent and food, and keep $3,000 to do whatever you want. You’re rich. But suddenly, you decide to build a gold-plated extension on your house that you will rent out later (CapEx). This costs you $4,700 a month (94% of your total). You have $300 left. If your car breaks down, or you lose your job, you’re in bad trouble.

That is exactly where Big Tech is now. To give you an example, Google—arguably the healthiest and best-positioned company among the magnificent seven to weather the incoming storm—has boosted the projected CapEx for the current year to $91-$93 billion (up from $52.5 billion in 2024). That’s almost twice as much. (Note, for context, that Google reported its best quarter ever, Q3 2025, at a revenue of slightly above $100 billion and estimates an average revenue of ~$400 billion in the current year.)

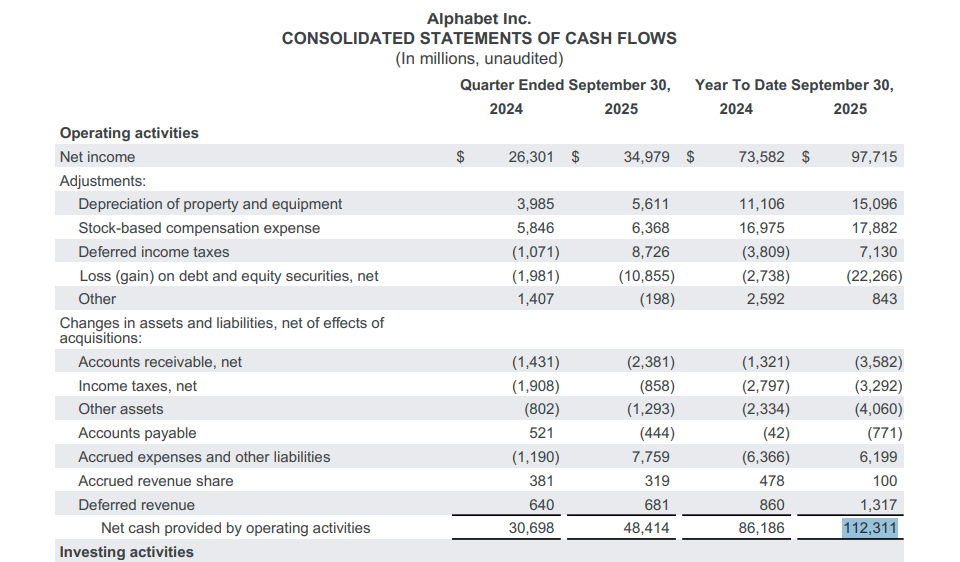

Still, with an operating cash flow of about $112.3 billion over the last twelve months (as of September), Google’s own CapEx guidance implies a free cash flow of roughly $20 billion.

All in all, Google is spending ~83% of its operating cash flow on capital expenditures (which is almost exclusively allocated to long-term AI projects nowadays). And that’s not counting the share buybacks and dividends, which Wall Street will surely demand! Google will have to dip into its savings! (Or, conversely, borrow money.)

And because spending ~80-90% of your income (and much more in some cases) on a construction project is uncomfortably close to “going broke” (big companies incurring bigger costs result in thin cushions and no room for maneuvering), they have quietly—none of this is done aloud, naturally—stopped relying on their bank accounts and have started swiping the credit card.

Since September, tech giants including Alphabet, Amazon, and Meta have issued nearly $90 billion in bonds. Oracle alone, which, in case you don’t remember, announced a deal with OpenAI to provide $300 billion in cloud capacity over the next years, issued $18 billion this year explicitly to fund “capacity expansions.”

So, Oracle boosts its projected revenues, but then it needs to borrow money to build the datacenters that OpenAI will rent to make the money to pay for the datacenters. Uh, oh. Besides, the $300B figure may never become real cash because it is itself based on OpenAI’s projections, which, in turn, depend on this whole AI thing going great. (The situation is so unsettling that even the hungry investors on Wall Street are wary: they sent Oracle’s valuation down $300 billion since the deal was announced.)

Standard borrowing isn’t even the scary part, though; the rise of “shadow debt” is. When a person takes out a loan, it sits on their credit report. If they have too much debt, their credit score goes down. Ok, fair. But tech companies are obsessed with their stock prices (which is basically their credit score), so they are finding ways to borrow money without putting it on their main books. They are using what is known as “Project Finance” or “Special Purpose Vehicles” (SPVs). As Carmen Arroyo writes for Bloomberg, “Financial engineering is back in style.”

The most glaring example came in September, when Microsoft announced a partnership with BlackRock called the “Global AI Infrastructure Investment Partnership“ (GAIIP). They plan to raise $30 billion in private equity to leverage up to $100 billion in total investment. By creating this separate entity, Microsoft effectively says, “We cannot put this $100 billion debt on our own credit card, so we’re going to open a joint account with a wealthy friend and put the debt there.” It keeps Microsoft’s balance sheet looking clean while the debt piles up in the shadows.

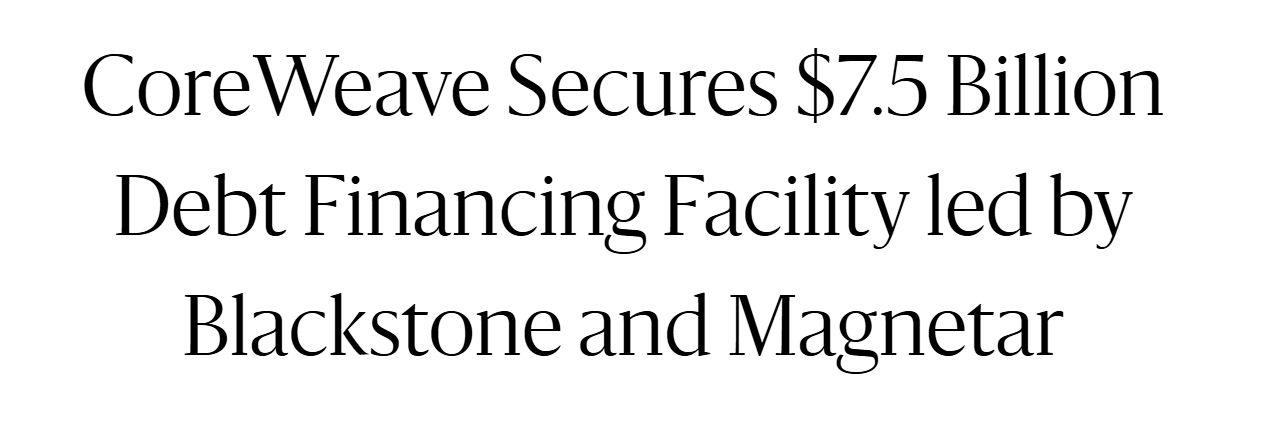

It gets worse. Look at CoreWeave, a cloud provider heavily backed by Nvidia. They raised $7.5 billion in debt financing led by Blackstone in 2024. The problem is that the loan was collateralized by the Nvidia chips themselves (not the first time they do this!).

This is the AI industry’s “ticking time bomb,” as The Verge puts it:

. . . except in the absolute best-case scenario of fast AI adoption, [CoreWeave] has no obvious path toward profitability. . . . I realized CoreWeave did make a horrible kind of sense: It’s a tool to hedge other companies’ risks and juice their profits. . . .

CoreWeave is “the poster child of the AI infrastructure bubble,” wrote Kerrisdale Capital, an investment manager, in a September note announcing it was shorting the stock. “Strip away the noise, and CoreWeave remains an undifferentiated, heavily levered GPU rental scheme stitched together by timing and financial engineering, not lasting innovation.” Kerrisdale thinks the fair value stock price of CoreWeave is $10.

CoreWeave went public at $40 a share (March 2025) and peaked at $187 a share (June). It’s $72 a share at the time of writing (November). Kerrisdale Capital says its value should be $10 a share (When? Soon). Holy moly. Elizabeth Lopatto, who wrote this fantastic feature on CoreWeave, knows what the real problem is: “What worries me most about CoreWeave is that I can’t figure out how on Earth it outruns its debt.”

The AI/tech industry does this all the time. These kinds of tricky financing tactics remain opaque to the general public. This is the definition of a bubble dynamic. Speculative risks might even be “fine” (an acceptable, perhaps expected kind of risk) if companies were just using non-existent AI-enabled profits to promise future spending commitments (looking at you, OpenAI) or making deals with future competitors (hello, CoreWeave), but it’s genuinely terrifying when we’re talking about liquidity crunch and operational fragility on the part of the largest tech companies in the world.

This is reminiscent of the housing crisis, where the asset (the house) was the guarantee for the loan used to buy the asset. As long as house prices went up, everyone was safe. But if the value of the house dropped, the loan became “underwater.” In CoreWeave’s case, they are betting that Nvidia H100 chips will hold their value forever (which we know is not true): What happens if a new, better chip comes out next year? Or if the demand for AI compute softens? Or if AI doesn’t generate the expected profits? The value of the collateral collapses; the debt remains.

Why should you, a normal person with a normal job, care about how Google pays for its servers? You should care because debt changes the physics of a company. When you fund expansion with your own profits, you are tethered to reality; you can only build what you can afford. When you fund expansion with debt, you are tethered only to belief and FOMO (fear of missing out). As long as the lenders believe AI is the “new electricity,” or, conversely, fear that they will be left behind (that is, they go in out of fear rather than conviction), they will keep signing checks.

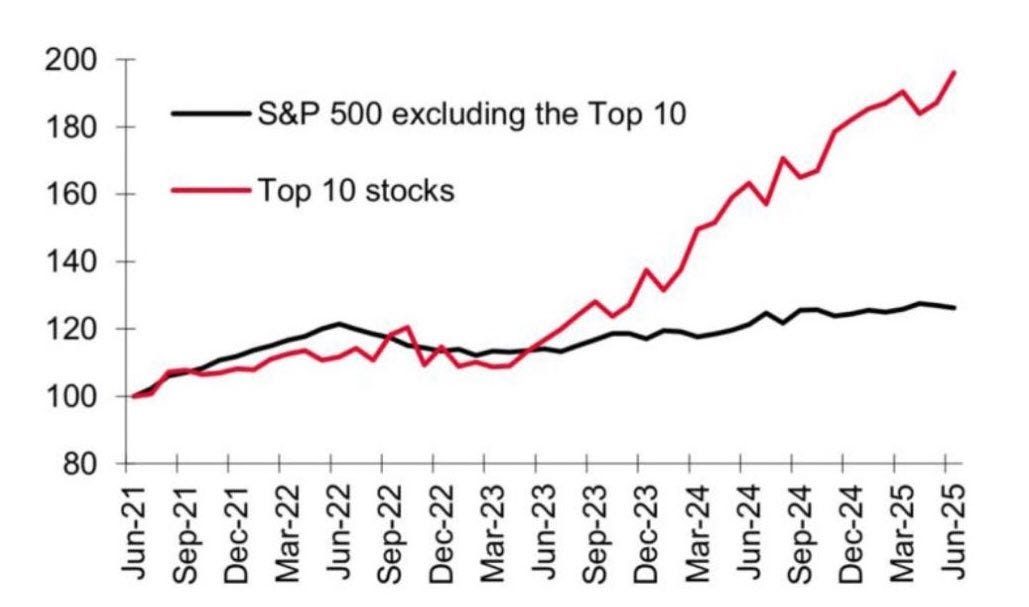

This makes the global economy precariously fragile. These companies are the backbone of the S&P 500 (actually, the S&P 500 is literally growing because they are growing); your 401(k) and your pension fund are effectively bets on their stability. If the revenue from generative AI—which is currently struggling to move beyond coding assistants and monthly subscriptions—doesn’t materialize fast enough to service these massive loans, the math breaks.

Without hyperbole: They are currently building the interstate railroad system for a world that has only invented the tricycle. And they are no longer paying for it with cash; they are taking out a subprime mortgage to do it.