You Have No Idea How Screwed OpenAI Is

An exhaustive overview of the situation

One of the recurrent ideas I’ve been hearing lately is that everything OpenAI is doing—from total product diversification beyond chatbots, into browsers, devices, chips, social media, etc., to immense deals across the board with Nvidia, Oracle, Broadcom, AMD, Amazon, etc., to the promises of AGI, superintelligence and the singularity, to the big contracts with the DoD, to the reported $500 billion valuation, to the possible IPO at $1 trillion valuation (around 2026-2027) after restructuring itself into a for-profit company—is with the sole objective of becoming too big to fail. (That’s the title of a Wall Street Journal article that was widely shared earlier this month.)

From this view, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman would be intertwining his influence, like a master weaver, across the economic layers—from consumer to enterprise to government—and transversally throughout culture and politics, so that, even in the scenario of an industrial bubble (AI works but there’s too much money on it) or insufficient returns from datacenter CapEx (AI works but doesn’t provide enough productivity gains), his empire is bailed out.

Economist Tyler Cowen wrote a countercurrent positive take for The Free Press. He argues that it’s good that the AI industry exists as an engine for the languid American economic machine, even if it’s the last remaining of its kind, and so it “makes perfect sense” for Wall Street to be obsessed with it.

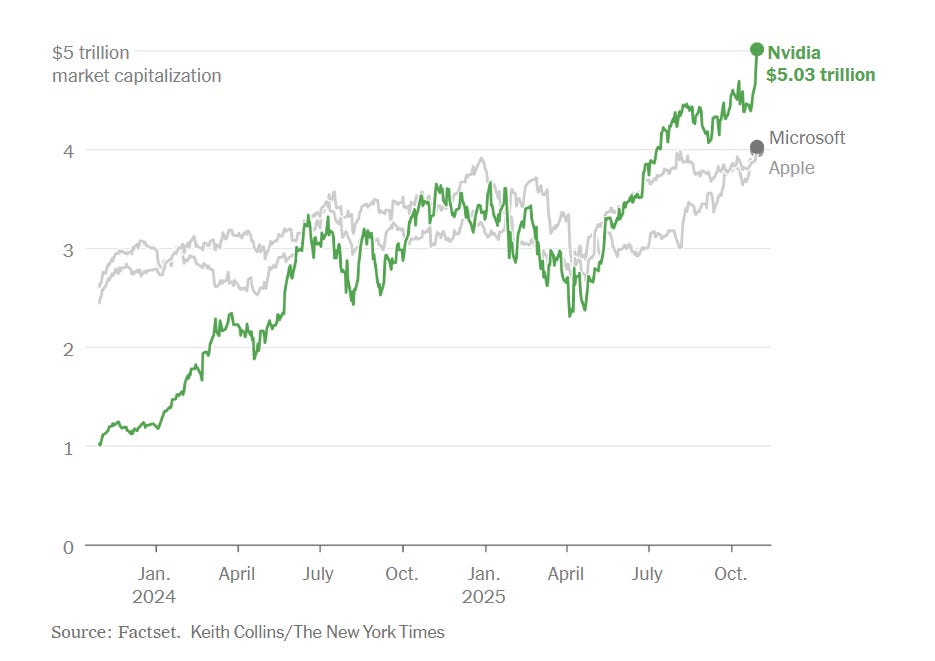

If Nvidia’s $5 trillion market cap is comparable to the GDP of Germany and Japan (I know the metrics are not apples-to-apples, who cares) or if OpenAI’s revenue is far from compensating for the losses (Microsoft’s last earnings report revealed OpenAI incurred a $12 billion loss just the last quarter), that’s not necessarily the sign of a bubble or the symptom of a recession, Cowen says, but a reminder that America specializes in turning the worst of times into the best of times.

Noah Smith—also an economist and a techno-optimist—has not been as positive lately, publishing what might very well be his most depressing piece in the last years: the world war two after-party is over. I sympathize with both Cowen’s and Smith’s views. On the one hand, it’s good to believe that AI could be the answer to the half-century-long decline of Western civilization. On the other hand, it’s hard to believe it.

So it’s pretty clear what conclusion we should take away from this, right? Economists are correct in re-stating, time and again, that their discipline is not an exact science.

The unsettling truth is that no one knows where the United States is going with the immense investment in AI (we do know where Europe is going with the absence of it, though), or what the constant soaring of the magnificent seven’s stocks mean, or whether it’s possible to sustain the economy with a bunch of companies that make deals with one another and sell, one the one hand, ads, and, on the other, chips to train AI models—to run more ads. So we wait. (I can’t help being a bit snarky with the most powerful industry in the world, my apologies.)

Tim Higgins argues in that viral WSJ article—”Is OpenAI Becoming Too Big to Fail?”—that OpenAI’s potential failure “could create a systemic risk” for the entire country.

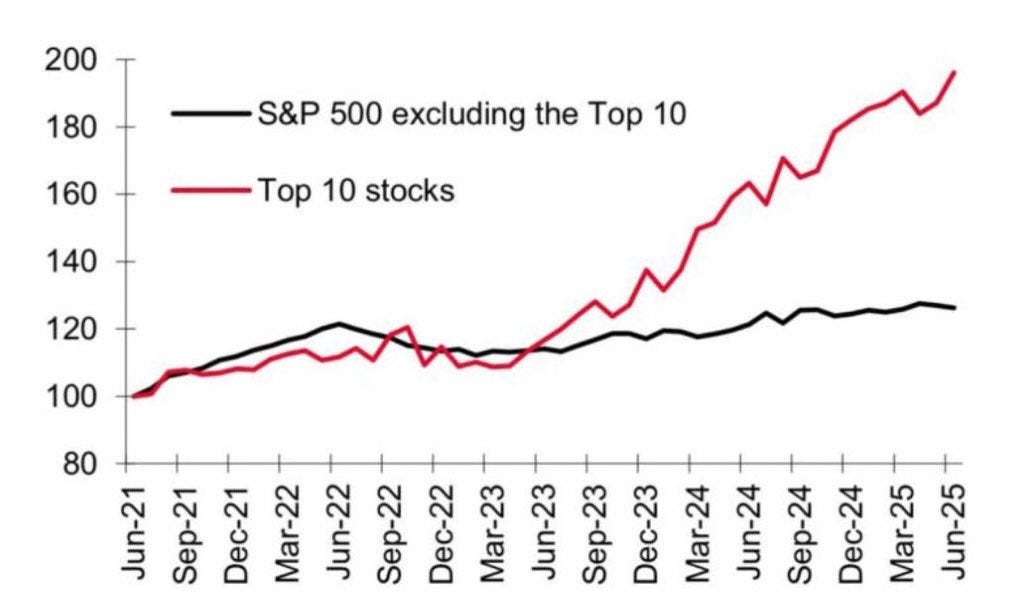

The argument goes like this: America’s GDP is growing exclusively due to seven big companies and a bunch of smaller ones; the S&P 500 is growing only thanks to the S&P 10; OpenAI has deals with half of them, totaling over $1 trillion. As the leader of the generative AI revolution, its demise would entail shareholder losses and thus distrust for the entire sector (in that scenario, an AI winter would be the least of our problems). That’s why OpenAI is becoming “too big to fail,” because the government would step in to prevent that systemic risk from turning into real danger.

That’s also what happened in 2008. Higgins notes the troublesome similarities (barring “liar loans and subprime mortgages”):

The linkages between these tech behemoths and the stock market’s dependence on them are notable. The lessons of the financial crisis earlier this century weren’t just that the banks were too big to fail, they were too interconnected to fail.

The big financial institutions were intertwined by a web of complex financial instruments and vehicles that threatened to bring down the U.S. system as certain players teetered toward collapse. This led the U.S. government to step in with a bailout package as well as take other unusual measures.

I have to admit the arguments are convincing: OpenAI looks not so much like an AGI company—a company that pursues artificial general intelligence as its ultimate goal—as a company that’s slowly realizing AGI might be a tad further away than it originally expected and is now rushing to ensure its survival. Is OpenAI big enough already to survive the fall? About that, kudos to Altman for this masterful performance.

First, he told us that OpenAI was this underdog, understaffed, undercapitalized open source non-profit AI lab that wanted to build AGI to benefit all of humanity, and we believed him.

Later, he told us that they needed more money than they expected to enact a post-scarcity utopia and cure cancer and such, and we believed him.

Then, he told us OpenAI needed to diversify and make deals with tech companies and the media and make slop and erotica and ads so that our dreams could come true, and we believed him.

Lastly, once we wake up from the hyperbole and the overpromises, and he tells us that he’s secured the survival of his empire, we will certainly believe him.

The question is: Is it that important if OpenAI is bailed out? I will enjoy as much schadenfreude as I can get from seeing Altman admit that he, perhaps, exaggerated a little bit all those things he told us.

So, if you read me for the chaotic takes, you’re in luck, because this article is actually a list of all the reasons why OpenAI could fail. Whether it’s saved before crashing into the ground is inconsequential to me. I only want to be able to say: “I told you.” Here you go: Five reasons why OpenAI is more screwed than you think.

1. The perpetual rivals: Google and DeepMind

Google and DeepMind are OpenAI’s best prepared competitors.

(Here’s a list of reasons why the others aren’t: Meta is scrambling to put together a stable team, Anthropic has no first-mover advantage, xAI is bleeding talent at a faster pace than Musk makes silly jokes, Microsoft AI’s CEO is Mustafa Suleyman, DeepSeek is struggling to gather enough Nvidia chips, although they may not need them for long, Apple has Apple Intelligence, but don’t worry, I don’t know what that is either.)

So, Google and DeepMind. I wrote this in April 2025, and I stand by it:

. . . two and a half years after the ChatGPT debacle, Google DeepMind is winning. They are winning so hard right now that they’re screaming, “Please, please, we can’t take it anymore, it’s too much winning!” No, but really—I wonder if the only reason OpenAI, Anthropic, Meta, and Co. ever had the slightest chance to win is because Google fumbled that one time. They don’t anymore.

The details have changed—OpenAI released GPT-5 and a slew of new products, and Google has solidified its offering—but the essence of the argument remains the same: the search giant has every major AI segment covered: models (across both price and performance), agents, multimodal, open-source, and all the complementary verticals: search, data, hardware, cloud, devices, apps.

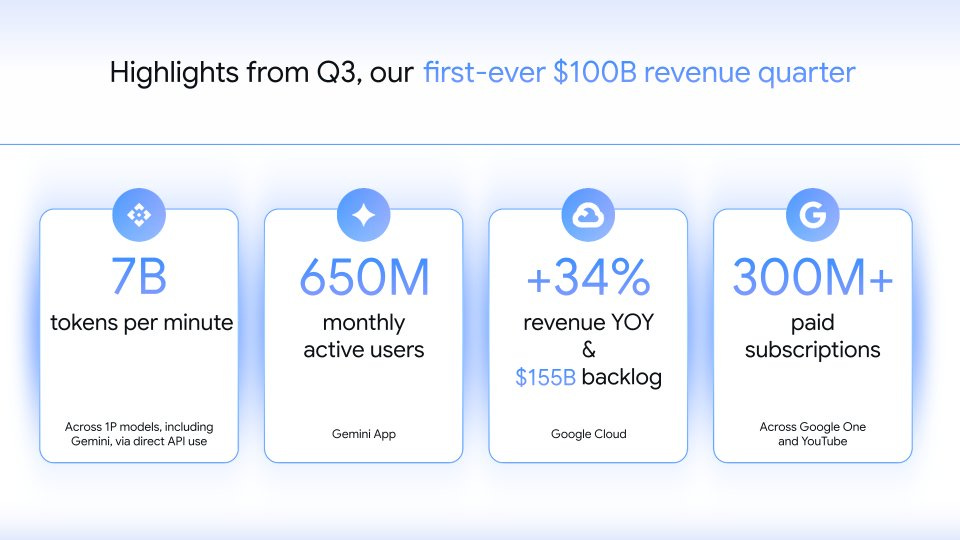

Perhaps most importantly, Google is posting crazy-strong revenue ($100B last quarter) and AI usage numbers (650 million monthly active users on Gemini), that rival with ChatGPT’s 800 million weekly active users.

What this means is that, while Google keeps improving its technology as it rises through the ranks in chatbot market share, it can exert a stronghold on OpenAI’s sole revenue source, which is ChatGPT, by keeping the prices low and lower. At this point, there’s not much difference between GPT, Claude, Gemini, and such, except at the highest level; they’re mostly interchangeable. OpenAI, not Google, is running against the clock; that’s why Altman is trying to establish a presence in other markets that could, if needed, offer OpenAI a lifeline.

Some people say that OpenAI’s true competitor is Meta, not Google or Anthropic, so Altman shouldn’t really be worried about Google. I firmly disagree.

This notion comes from the fact that OpenAI will have to push for social media + advertisement revenue (that is, Meta; The Information calls this the “Meta-fication of OpenAI”) once it realizes people are not willing to pay for ChatGPT the amount it needs to cover the training and inference costs.

ChatGPT has around 40 million paid subscribers (5% of the total active userbase), and OpenAI still lost $12 billion last quarter. Even if user revenue is growing rapidly, which is a silver lining to them for sure, it has a ceiling (Meta and Google have so much revenue because they don’t rely on us paying them but on advertisers’ money).

“Well,” you may say, “even if individual consumers won’t pay, then enterprises will.” True, which leads me to the next point.

2. Anthropic is winning the AI enterprise market

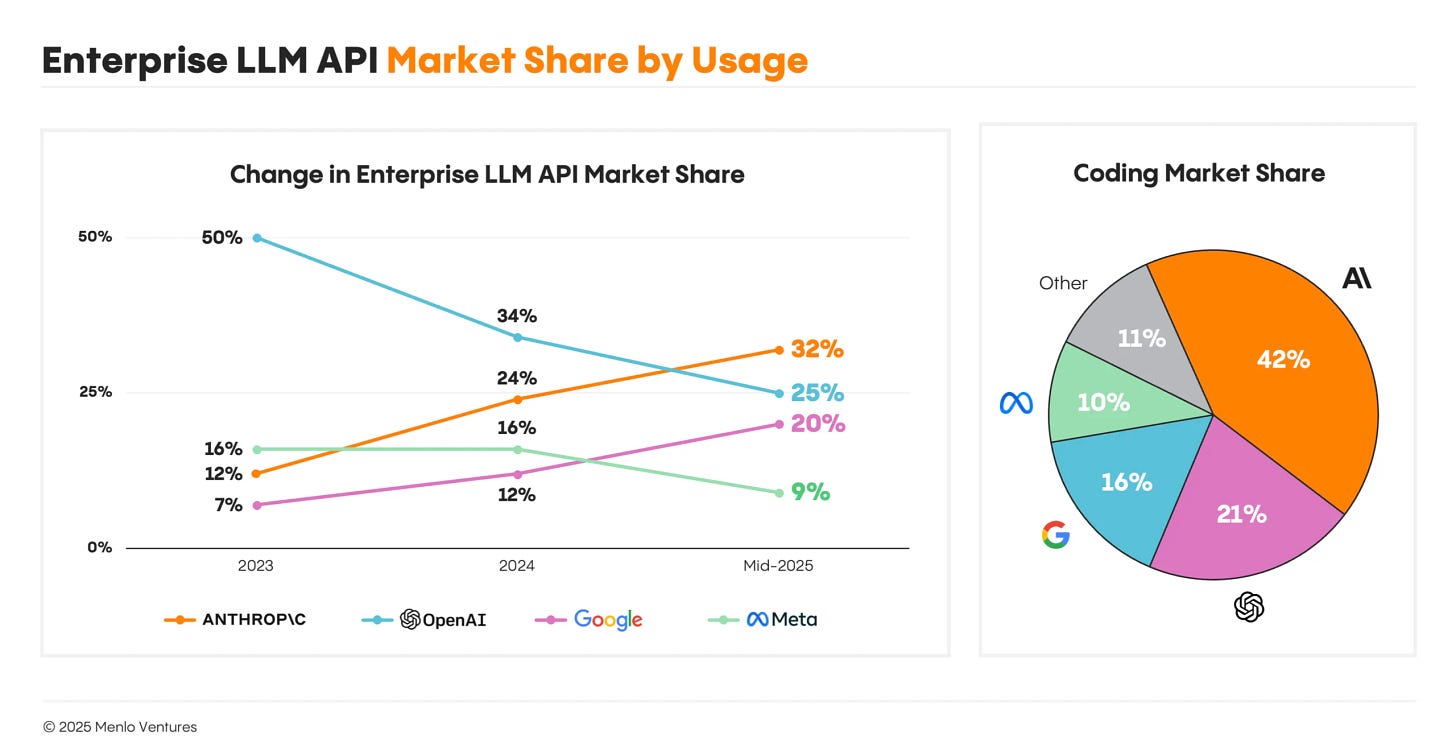

This is a big deal. Menlo Ventures, a VC firm, has been covering the evolution of the enterprise market for the past few years. Recently, they released a new report revealing that, for the first time since OpenAI launched ChatGPT in 2022, it lost the lead on the enterprise market to Anthropic. (Given current trends, I believe that Google will have also beaten OpenAI by 2026, which further reinforces my points.)

By the end of 2023, OpenAI commanded 50% of the enterprise LLM market, but its early lead has eroded. Today, it captures just 25% of enterprise usage—half of what it held two years ago.

Anthropic is the new top player in enterprise AI markets with 32%, ahead of OpenAI and Google (20%), which has shown strong growth in recent months. Meta’s Llama holds 9%, while DeepSeek, despite its high-profile launch at the beginning of the year, accounts for just 1%.

The straightforward read is this: Coding is the killer app and enterprises prefer Anthropic models (Claude Code, Sonnet 4.5, etc.) to OpenAI’s (Codex, GPT-5, etc.). Menlo Ventures writes: “Claude quickly became the developer’s top choice for code generation, capturing 42% market share, more than double OpenAI’s (21%).” (Notice that Anthropic has as many Claude subscribers worldwide as OpenAI has ChatGPT paid subscribers, around 40 million, which makes this stat even crazier.)

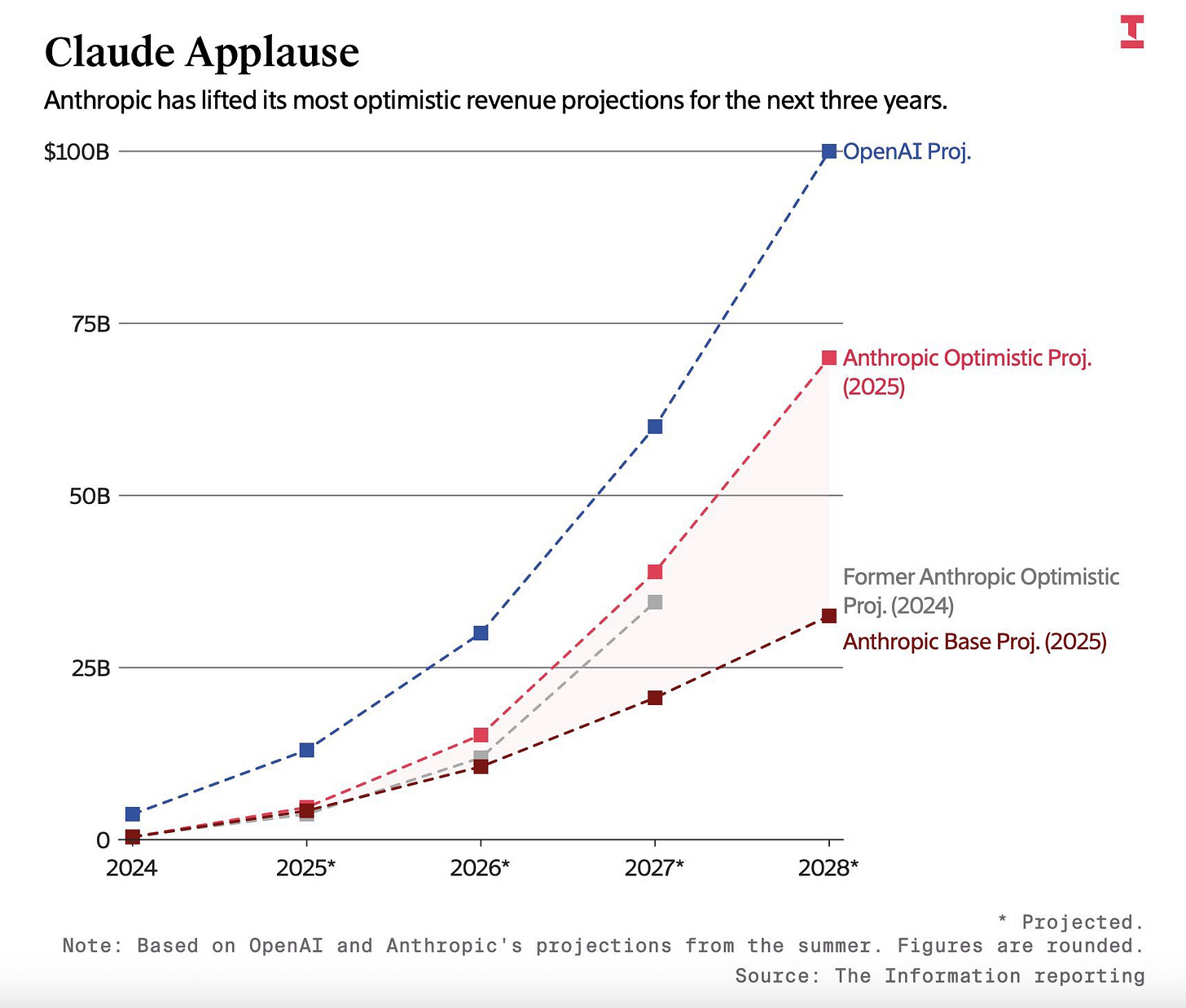

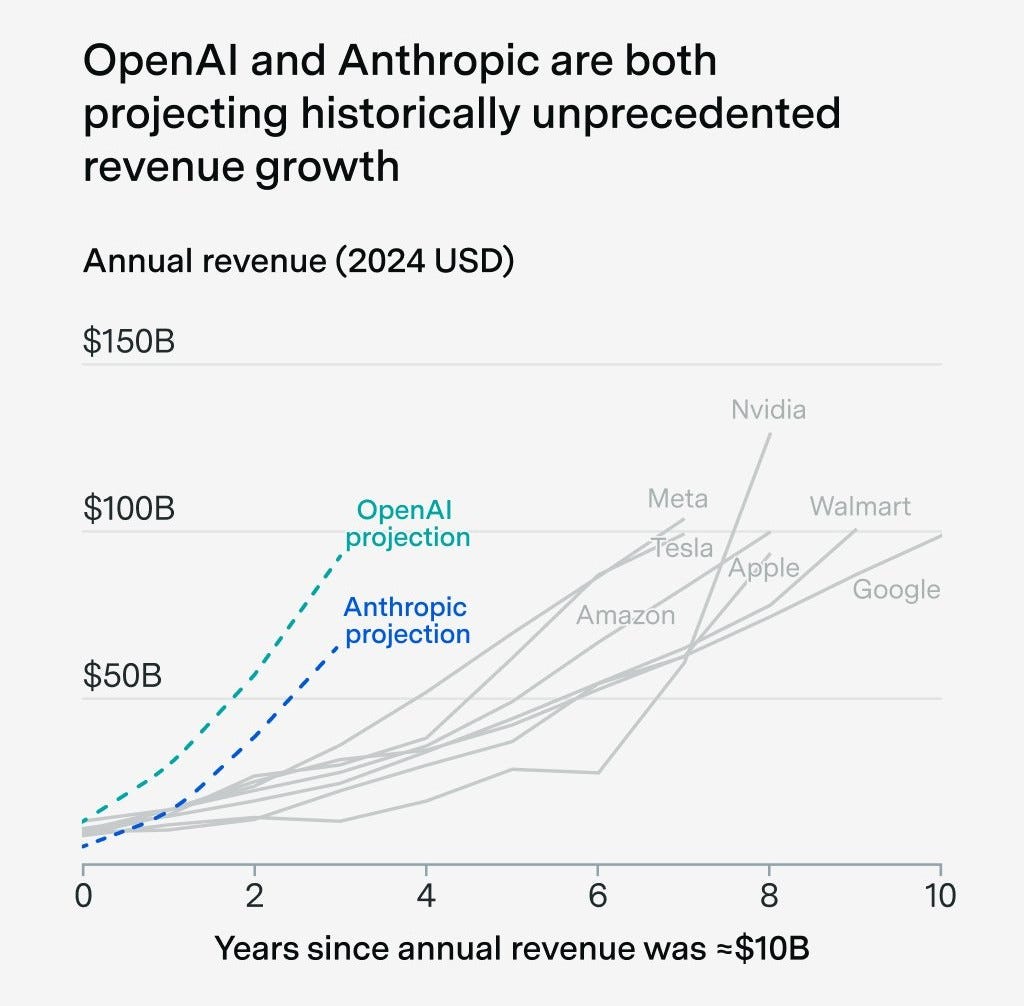

Anthropic is confident in its enterprise growth to the point that it projects profitability by 2028 (optimistically), whereas OpenAI projects it by 2029. If this comes to pass, both would mark unprecedented growth (OpenAI’s revenue projection is higher than Anthropic’s because it serves many more users, so it makes more money but also incurs higher costs). This is how they compare to one another and other tech companies:

But leading the enterprise market is relevant beyond revenue share: big contracts are what matter for AI companies. OpenAI is happier that it landed a $200 million contract with the DoD than it is for having 40 million people paying $20/month, which amounts to $800 million per month. Why? Because subscriptions come and go, people’s loyalty is brittle, and the average user wields no power to reshape the world. The Department of Defense, however, is as good a client as a tech company can get. (That’s why Silicon Valley has militarized.)

The reason why I believe in this counterintuitive assertion—that $200 million in DoD money is more valuable to OpenAI than $10 billion in subscription revenue—is that ChatGPT won’t be a business-to-consumer (B2C) product forever.

Generative AI is, fundamentally, a business-to-business (B2B) technology in the sense that to be worthwhile—and for revenue to be in the $100B+ zone and stable over time—it must be instantiated as a baseline across the economy, like electricity and the internet and such. The fact that we’re all stuck using standalone chatbots reveals we’re in the early days (or, conversely, that the technology is too expensive to do anything else, but that’s another question). OpenAI doesn’t want to sell you $20/month subscriptions, but your employer $20000/month services.

For OpenAI, losing B2B market share might be a negligible nuisance in the short term, but it definitely is a long-term existential risk.

3. Sam Altman’s non-consistent candidness

Elon Musk, co-founder of OpenAI, is not happy that Sam Altman went ahead with the restructuring from non-profit to capped-profit to for-profit. As a result, he sued OpenAI. The lawsuit is ongoing.

During his deposition for the case, OpenAI’s co-founder and former chief scientist, Ilya Sutskever, revealed that he and Mira Murati, former CTO, had been thinking about removing Sam Altman as CEO for a year before the November 2023 boardroom coup took place. The reason, and I quote from the “plan document” that was revealed during his deposition (transcribed), is that “Sam exhibits a consistent pattern of lying, undermining his execs, and pitting his execs against one another.” This goes in line with the board’s report after the 2023 coup on Altman’s behavioral patterns:

Mr. Altman’s departure follows a deliberative review process by the board, which concluded that he was not consistently candid in his communications with the board, hindering its ability to exercise its responsibilities. The board no longer has confidence in his ability to continue leading OpenAI.

There’s a larger database of similar claims in The OpenAI Files, a report created with independence of OpenAI or any competitor, including Elon Musk, and guided by a “commitment to corporate accountability and public interest research.” Here are a few examples relevant to the case against OpenAI, and Sam Altman in particular:

Mira Murati: “I don’t feel comfortable about Sam leading us to AGI.”

Ilya Sutskever: “I don’t think Sam is the guy who should have the finger on the button for AGI.”

Geoffrey Irving: “My prior is strongly against Sam after working for him for two years at OpenAI.”

Scott Aaronson: “It now looks to many people like the previous board has been 100% vindicated in its fear that Sam did, indeed, plan to move OpenAI far away from the nonprofit mission. . .”

Dario and Daniela Amodei [From Empire of AI]: *“*To people around them, the Amodei siblings would describe Altman’s tactics as ‘gaslighting’ and ‘psychological abuse.’”

There are many more testimonies from lesser-known former staff at OpenAI, but all of them reveal the same pattern. I understand Altman is a wartime CEO, a deal-making CEO, but is he the CEO OpenAI needs to survive this next delicate phase? I can’t help but wonder how much of Anthropic’s success is due to CEO Dario Amodei’s more trustworthy demeanor? Or how much of Google’s recovery is due to DeepMind’s CEO Demis Hassabis’s integrity? I’d bet a whole lot.

As I wrote in an article criticizing the industry’s predilection for hyperbole and exaggeration (Altman is not alone in this, but he’s inarguably its maximum exponent): “When you play the game as if words, not substance, are the only thing that matters, don’t be surprised when the world holds you to the same standard. . . . if bullshit is [your] currency and empty words [your] weapon, [you] may as well be paid in kind.”

As we say in Spain, you catch a liar before you catch a cripple.

4. Altman doesn’t like to be asked hard questions

Many of you have probably already seen this video.

It’s a clip of Sam Altman and Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella’s appearances on Brad Gerstner’s podcast (Gerstner is an OpenAI shareholder):

Here’s a transcript of the relevant part (11:54) in case you don’t want to watch it:

BG: The biggest quesiton hanging over the market is: How can a company with $13 billion in revenue make $1.4 trillion of spending commitments? You’ve heard the criticisms, Sam—

SA (interjecting): First of all, we’re doing well more revenue than that. Second of all, Brad, if you wanna sell your shares I’ll find you a buyer. . . . Enough. I think there’s a lot of people who’d love to buy OpenAI shares—

BG (interjecting): Including myself. Including myself.

Altman goes on to say that revenue is “growing steeply” and that they project it to keep growing steeply and so on and so forth.

What surprised me was Altman’s immediate reaction to a question that’s perfectly reasonable given the contrast between current revenue and spending commitments: “You are making $13 billion (does it really matter if it’s even twice as much? Come on), so how are you going to spend $1.4 trillion?” Legit. “How are you going to 100x your revenue so that you can pay for all of that compute and energy?” Legit.

Gerstner remarks that he’s happy to be an investor, which means that he’s not asking out of distrust or fear but out of due diligence: “As an interested investor, can you explain to me how you plan to achieve this?”

It’s a choice to answer with an argument or a tantrum.

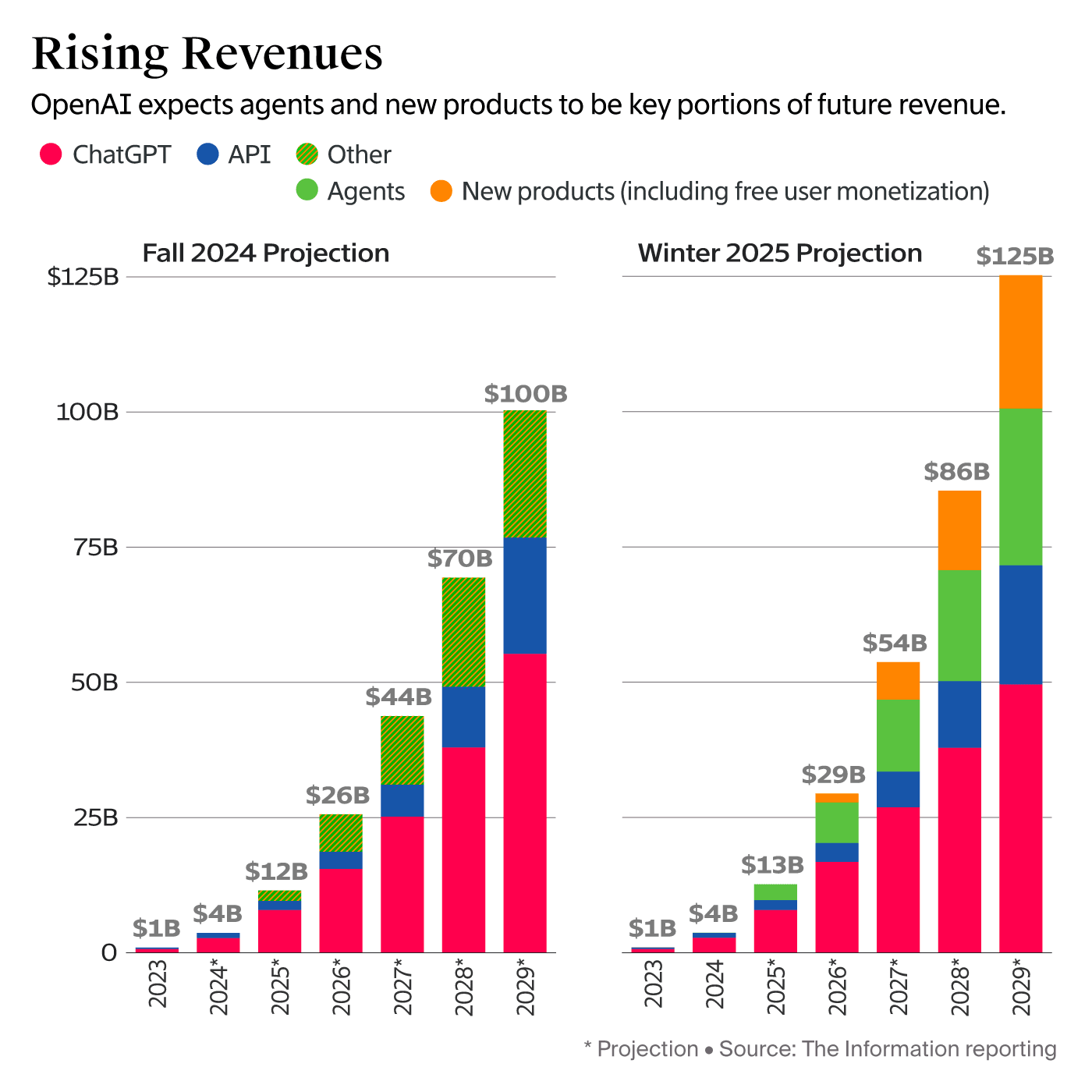

For reference (to give Altman credit where it’s due), OpenAI’s reported revenue (Altman says they’re doing more than that, and it could be, but there’s no official data) has grown drastically over the past years (you saw it in those graphs above), from $1B in 2023, to $4B in 2024, to $13B in 2025, projected up to $100+ billion by 2029.

However, there’s a new data point I’ve mentioned twice already, that we only know because some people are really good at financial archaeology: OpenAI made a $12B loss in the last quarter alone. This only adds fuel to Anthropic’s enterprise lead and Google’s industry-wide stronghold. Again, from $1B to $13B in two years is crazy growth, but does it scale like those AI models seem to do? I guess we will see.

5. Over-diversification is a risky business

This is a cause of all of the above: OpenAI is trying too many things at once.