The Shape of Artificial Intelligence

What AI really looks like

I. Spooky shapes at a distance

The shape of things only becomes legible at a distance.

For instance, history demands temporal distance. The phrase “the Western Roman Empire fell in 476 AD” only became a fact once historians began to investigate the entire period by zooming in and out on the primary sources, compressing a gradual transformation into a clean endpoint. While the deposition of Romulus Augustus, the last Western emperor, was recorded at the time in 476 AD, its status as the fall emerged later, when distance allowed patterns across centuries of political and administrative decay to crystallize into the shape of a broken empire.

Distance can also be spatial rather than temporal. In Peru, large ground drawings—now known as the Nazca Lines—were used as markers or signals on the landscape. From ground level, they are difficult to interpret. Their meaning only becomes clear when viewed from above, where the full shapes can be seen at once.

Although AI is nearing its 70th birthday, it’s been only five years since ChatGPT was launched, eight since the transformer paper was published, and thirteen since AlexNet’s victory on the ImageNet challenge, which implies the deep learning revolution is barely a wayward teenager. I think, however, that we must try to give a clearer shape to the current manifestation of AI (chatbots, large language models, etc.). We are the earliest historians of this weird, elusive technology, and as such, it’s our duty to begin a conversation that’s likely to take decades (or centuries, if we remain alive by then) to be fully fleshed out, once spatial and temporal distance reveal what we’re looking at.

(In Why Obsessing Over AI Today Blinds Us to the Bigger Picture, one of my favorite essays of 2025, I argued that new technologies take a long time to settle into our habits, traditions, and ways of working. So long, in fact, that trying to end the discussion early with a definitive theoretical claim—“AI art is not art because X”—misses the point. That kind of claim was the core of an essay by science-fiction author Ted Chiang, published in The New Yorker in 2024, which I addressed in my piece. I still stand by my position. To be clear: this article is not trying to make that sort of argument.)

One reason why this conversation needs to happen now, before AI is fully mature, is that even if its shape promises to keep morphing for a while, the effects are taking place already. There’s a huge overlap of the different stages of the AI pipeline. All of this is happening at the same time: experimental research (e.g., TRMs, multimodality), engineering techniques (e.g., distillation, CoT, or RLVR), optimization of the stack (e.g., better GPUs or infra), the iterative productization of models (e.g., OpenAI: GPT-3 to ChatGPT web to ChatGPT app to a myriad of peripherals like Codex, Sora, Atlas), and the continued adoption and diffusion at the application layer (e.g., companies like Cursor and specific enterprise solutions like BloombergGPT).

In short, research, engineering, infrastructure, product, design, and sales departments are all busy. This total overlap gives the current period a characteristic tone and texture of uneasiness and uncertainty; you take measures to adopt or fight new AI products and practices, and tomorrow, some study or report comes out that makes your approach obsolete.

This is going to happen for years still. That’s why the conversation around the shape of AI is fundamental: you can only know what to do or think, or predict if you know what the object of your actions, thoughts, and predictions looks like. So far, there’s been little clarity on that. The best way to lift some of the fog is by comparison with the object closest to AI that we know of: humans. The comparison is flawed in many ways (anthropomorphism and all that), but that’s precisely why I’m writing this: I want to point out the flaws at the same time that I highlight the virtues of the analogy.

II. The techno-optimist’s blob

For a long time, the prevailing narrative has been one of gradual encroachment. We imagine human capability (I will use capability, intelligence, and skill interchangeably) as a fixed territory, a fortress—or, to choose a visually gentler metaphor, a circle—and AI as a growing organism that is slowly but surely covering that ground. I’ve written about this on the domain of chess (and how it might play out for every other domain) in Human → Superhuman → Ultrahuman:

In the span of little more than 20 years, Computers went from “brute-force methods may solve chess” to “[it’s] impossible for humans to compete,” to “impossible for humans to help.”

That’s just one case of many. The bottom line is that AI started as a dumb, narrow system (e.g., expert systems in the 70s-80s or AlphaZero in 2018) but will eventually become super smart, broad entities capable of solving problems in any discipline.

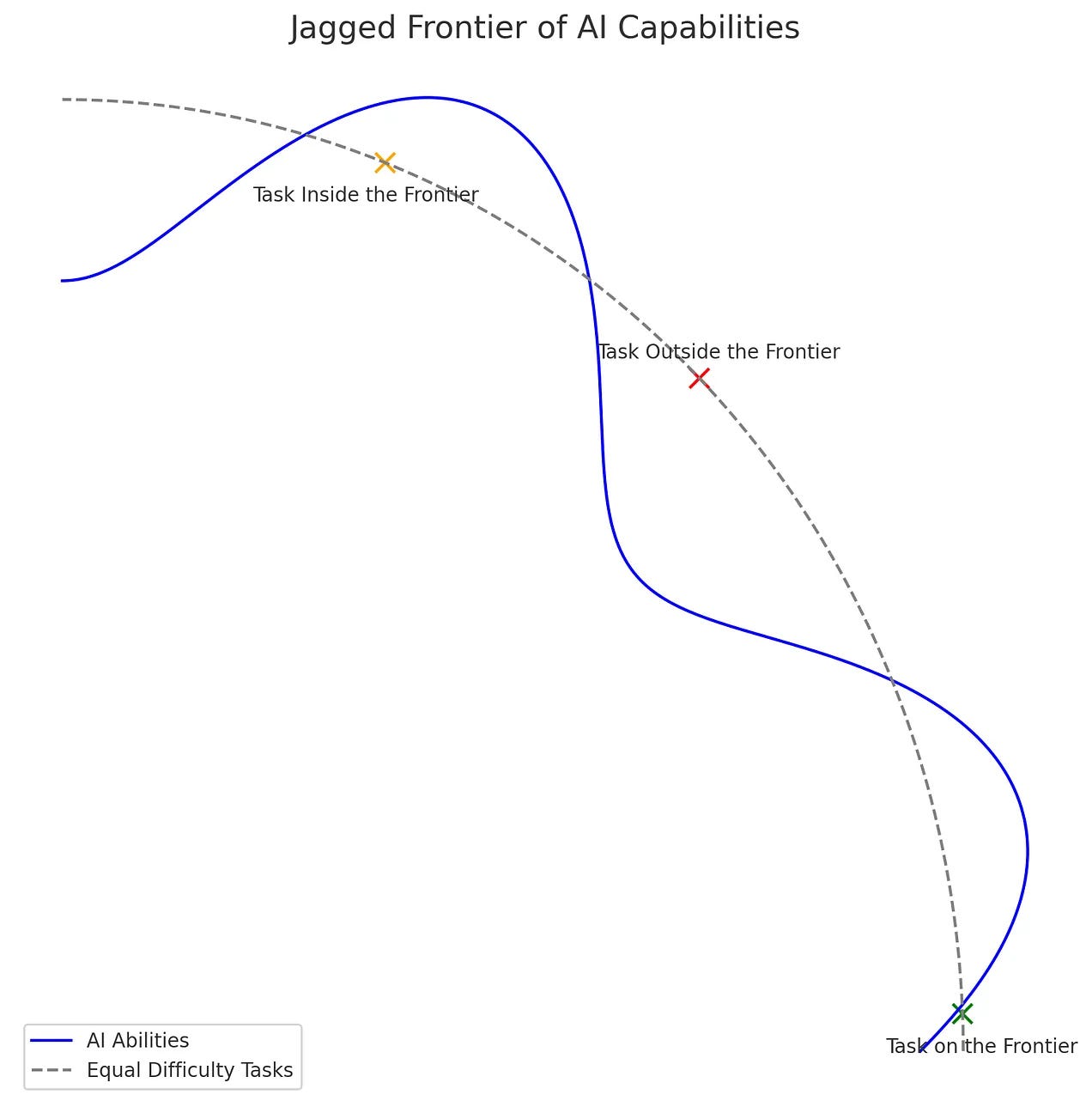

This narrative gave birth in 2023 to the concepts of the “jagged frontier” and “jagged intelligence,” a more fine-grained metaphor about the “shape of AI” based on empirical results rather than theoretical hypotheses. The idea, popularized by a study involving BCG consultants (and particularly by Wharton professor Ethan Mollick’s blog post, Centaurs and Cyborgs on the Jagged Frontier, and later AI scientist Andrej Karpathy), is that AI capability isn’t a smooth line (or a smooth circle like human capability) but jagged with respect to tasks we humans consider “equally difficult”:

Inside the circular frontier of human capability, the AI is a superhuman genius or soon to become one (e.g., chess or recognizing faces) due to its superior computing power and speed.

Just a step outside of it, it fails at tasks a child could perform (e.g., ARC-AGI 3 games or never failing to count the r’s in the word “strawberry”).

When the jagged frontier of AI capability and the circular frontier of human capability meet, the AIs and humans are “tied” (e.g., maybe writing and coding? It changes too fast).

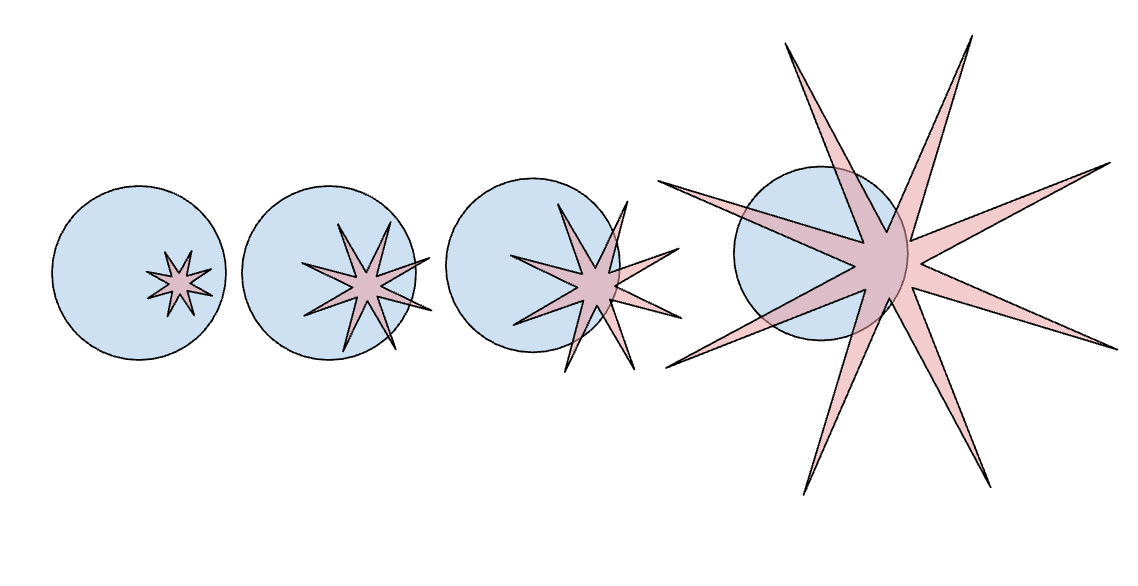

Here’s Mollick’s visualization:

As of now, the jaggedness leaves some human-covered territory out of AI’s grasp. We live, as I wrote two months after Mollick coined the term, in a “beautifully balanced instant” of AI-human interaction:

From a historical vantage point, we are experiencing a beautifully balanced instant where humans exist, at the same time, on both sides of the “jagged frontier,” a line that defines the threshold of AI’s effective competence (i.e., performance). If we drew the human frontier, defining what we can do at our best, we’d see, very clearly, that more than ever before and more than ever again, both frontiers intersect everywhere.

Soon, the story goes, the jaggedness won’t matter; AI will have surplus intelligence across the board, to the point that any human participation will be a hindrance. That’s what I called “ultrahumanity.” It happened in chess, why not everywhere else? However, how we visualize this jagged shape matters because, remember, our metaphors define what we think and thus what we predict and thus how we act. Turns out, popular illustrations might hide a stranger reality.

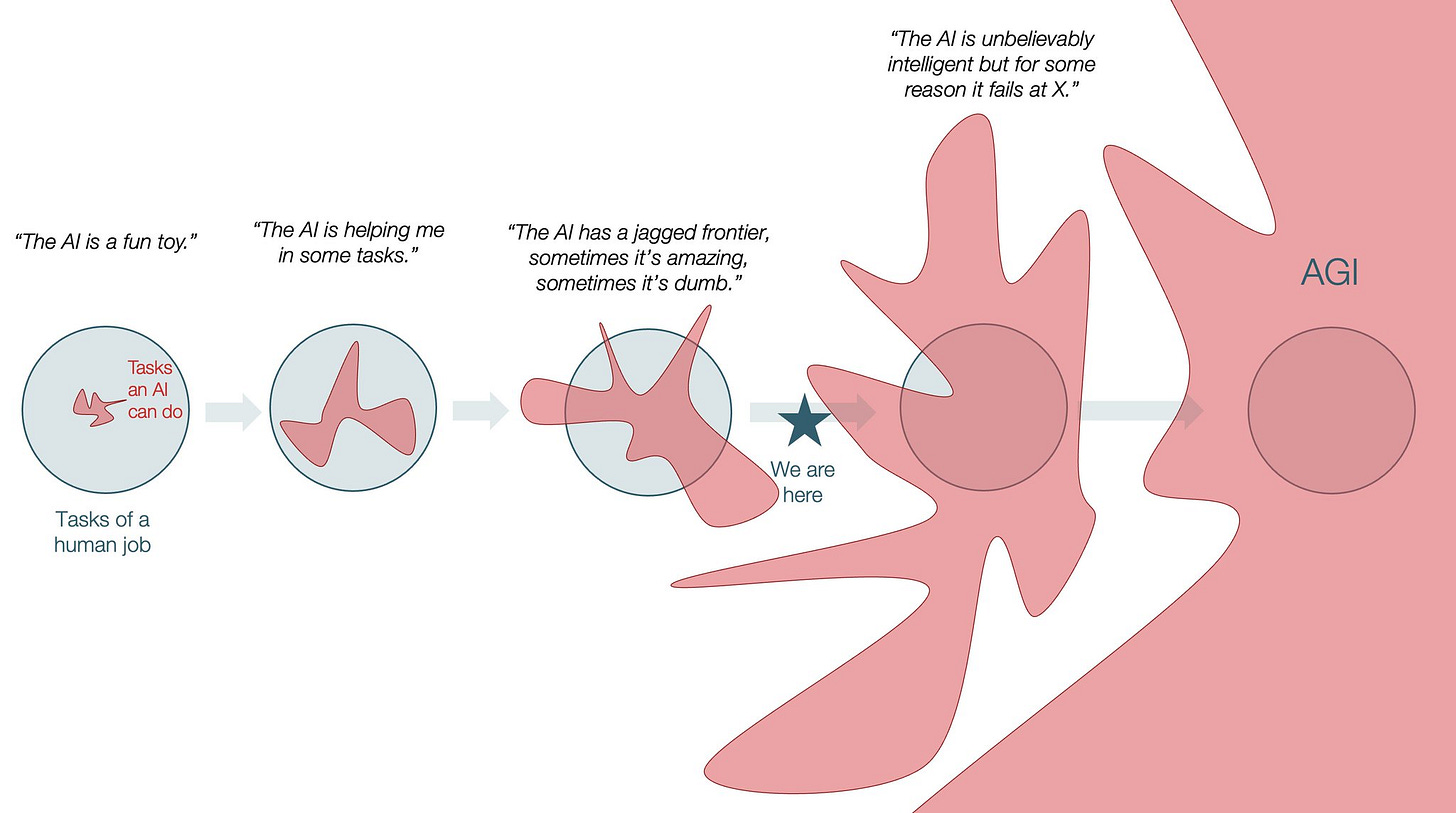

People in the “scaling laws will fix everything” camp—who nonetheless accept the jagged frontier—tend to picture AI’s progress the way writer Tomas Pueyo did in this time-based sketch:

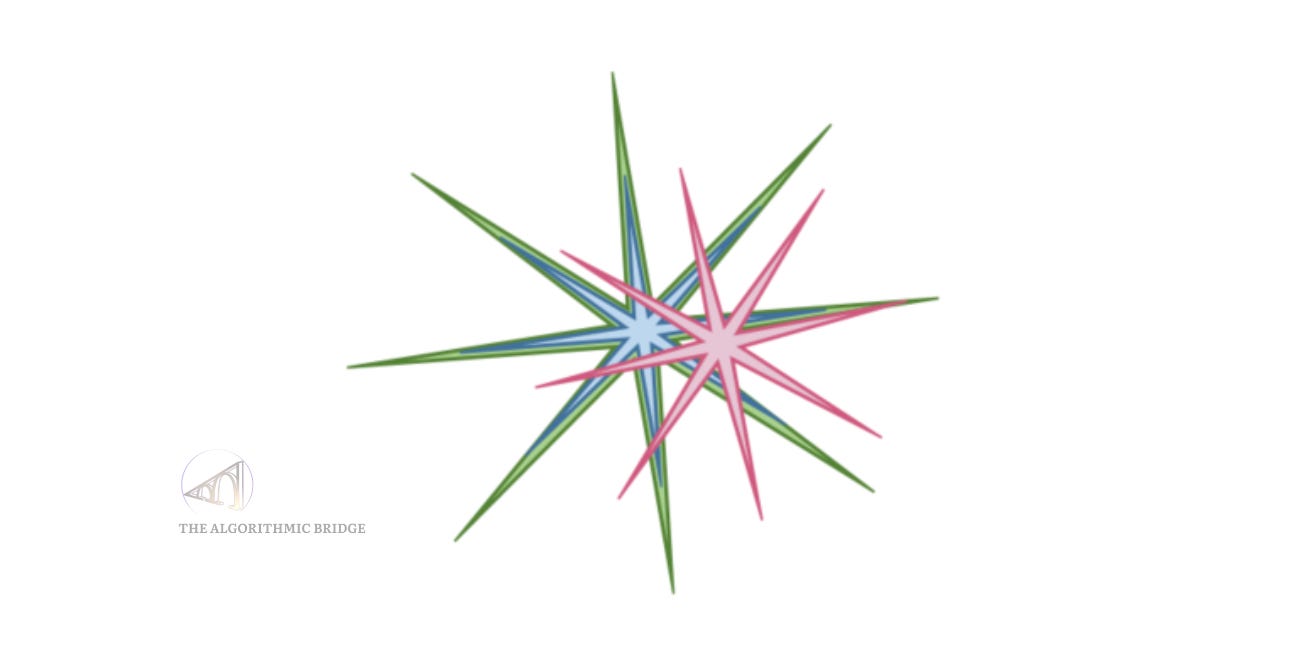

Here, human capability is represented by a clean, blue circle. It contains everything a human job entails: creativity, logic, empathy, rote tasks, planning, etc. (It could also contain other things, like love or thinking about oneself, but let’s keep it simple.)

The AI is represented by the pink-ish shape. In the beginning—“AI is a fun toy” and “AI is helping me in some tasks” stages—the AI is a small, irregular blob inside the human circle. As the models scale and improve, the blob grows. It develops “jagged” protrusions, large spikes of capability where it excels, often beyond human capability. The narrative here is linear and inevitable: the blob gets bigger. Eventually, it covers >90-95% of the blue circle of human skill, achieving what we might call AGI, artificial general intelligence (or human-level intelligence), and then expands beyond it into the vast pink-ish ocean of superintelligence.

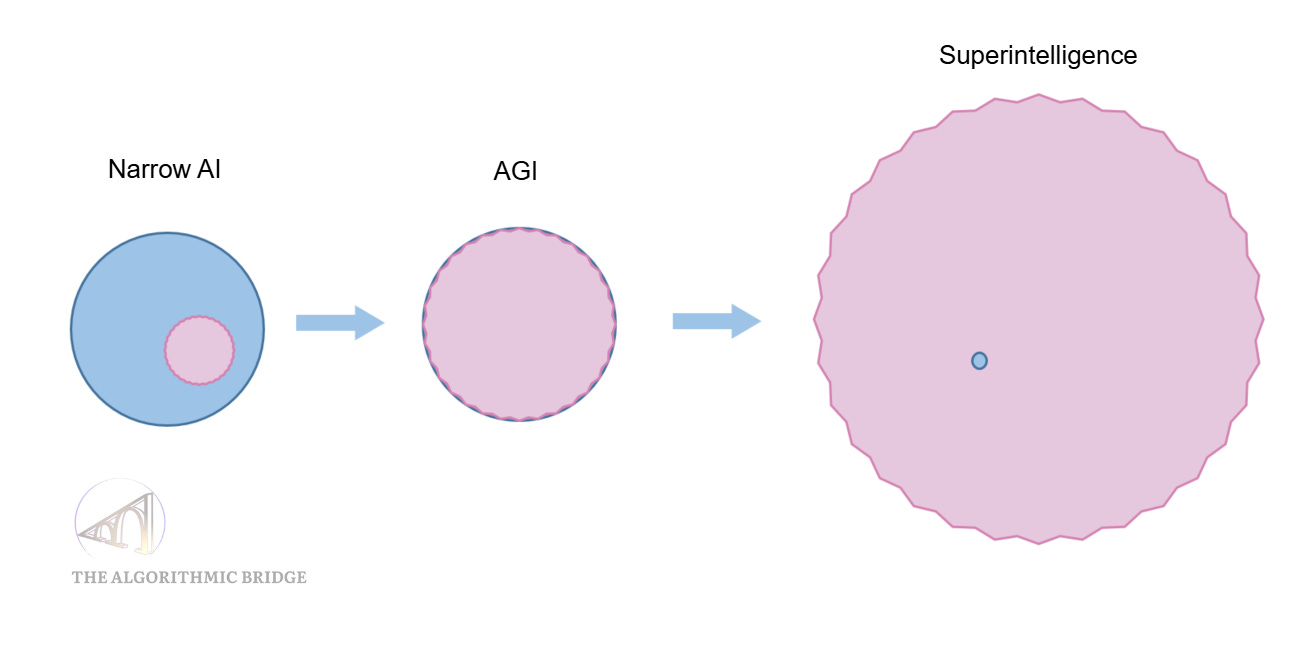

Pueyo labels this last stage “AGI,” but AGI, as defined normally, would be a pink circle that overlaps ~100% with the blue circle and not beyond that (a positive ratio of jaggedness would prevent AGI from ever happening, jumping AI from “How can it fail these dumb tasks?” to “OMG, I can’t even imagine all the things it can do!!”). It would look something like this:

Pueyo’s image is comforting in its simplicity: it’s easy to understand and easy to believe. It suggests that the “jaggedness” is a symptom of AI’s immaturity and only matters insofar as AI is immature. Give it more compute, more data, more algorithmic breakthroughs, and the gaps between the spikes will fill in. From our point of view as inferior intelligent beings (by then, “inferior intelligent beings” would be a fair label), the blob will simply become a vast ocean beyond our conception, beyond the limits of our sense-making (I touched on this in GPT-4: The Bitterer Lesson).

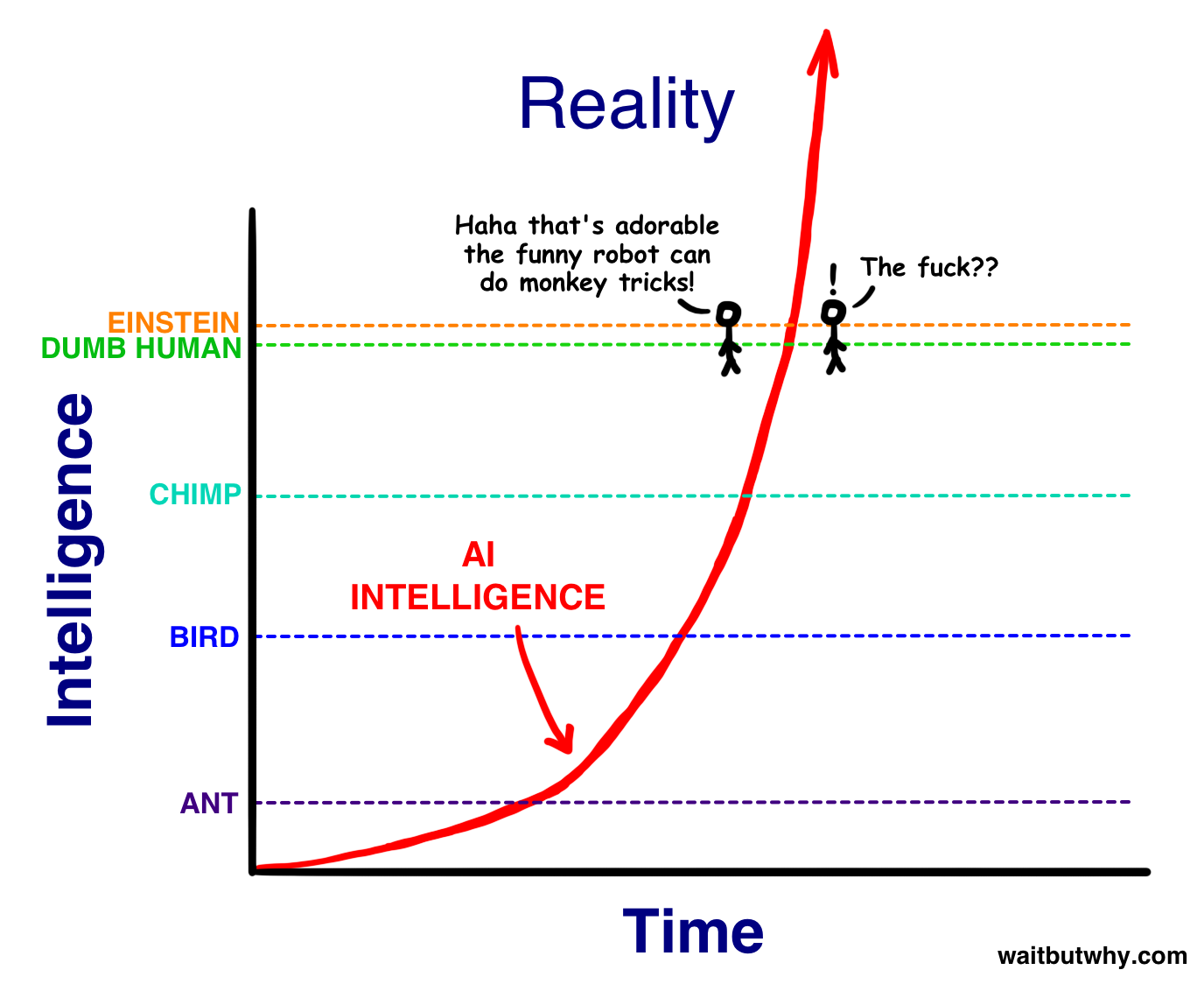

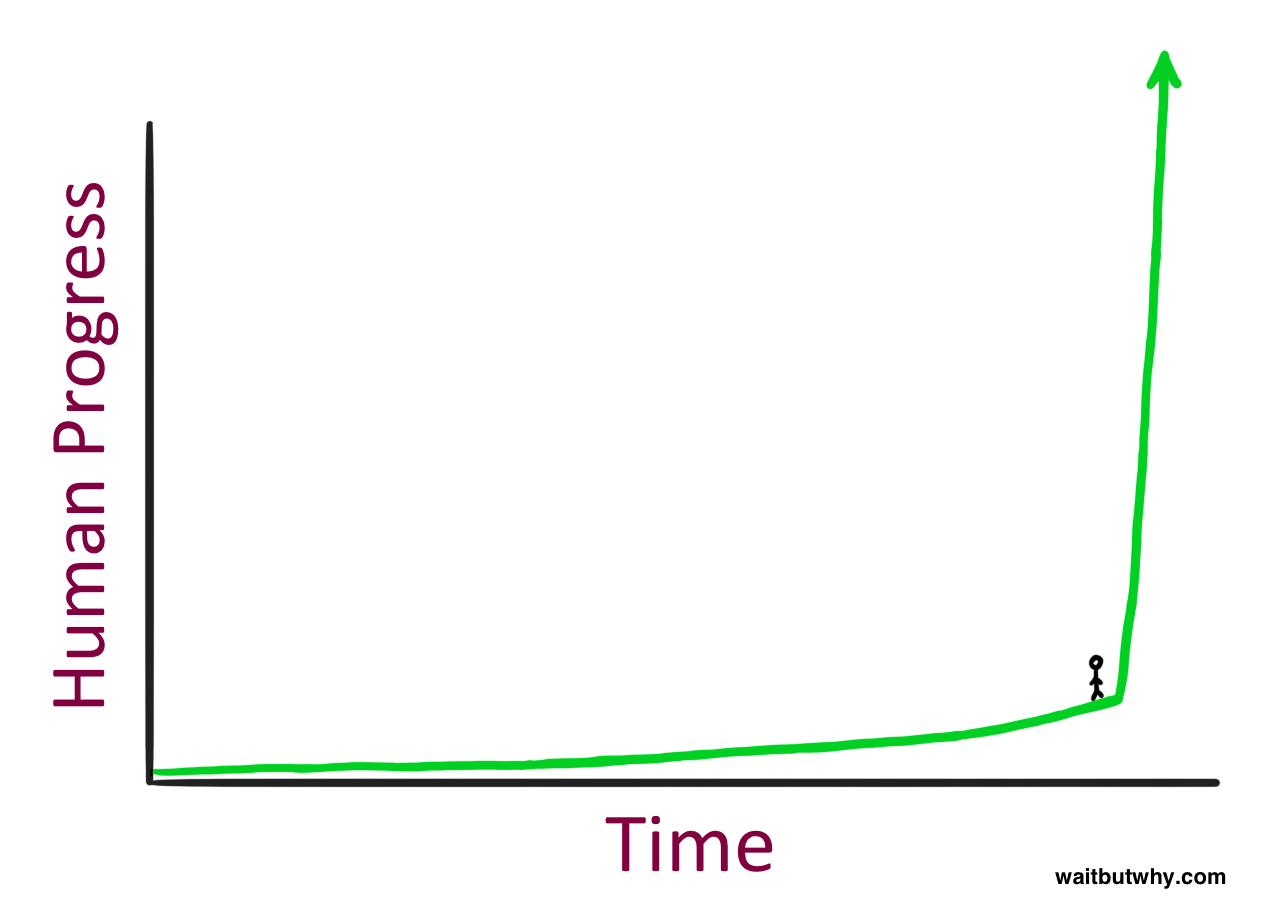

Some people think the progression until we get a vast pink ocean of AI superintelligence will be fast. Others say that, on top of being fast, it will be sudden. Tim Urban, author of Wait But Why, conceived the most famous depictions of this scenario eight years ago:

I have two big qualms with this portrayal of the jagged frontier, or jagged intelligence, in particular with the progression that Pueyo illustrated so nicely.

One is the blue circle of human capability. This bias isn’t new. It dates back to 1904, when psychologist Charles Spearman identified the g factor (beloved by IQ evangelists and hereditarians). Spearman noticed that people who performed well on one cognitive test tended to perform well on others, suggesting a single, underlying mental energy. For over a century, this single variable view has conditioned us to see intelligence as a linear spectrum, a ladder you climb (I used this metaphor in Being Weird Is Your Superpower), or a circle you fill.

Another is the assumption that, as AI improves, it becomes better at everything, in contrast with it becoming better at some things but not others (and thus not covering the human circle anytime soon; perhaps never). On this view, the jaggedness is not a temporary feature of this interstitial moment but perhaps a fundamental feature of AI’s alienness.

In short, there are a few flaws in this geometry that Pueyo and Mollick inadvertently perpetuate. Let’s see what this means and how the above visualizations change when we introduce these corrections.

III. The spiky star of intelligence

Data scientist Colin Fraser looked at Pueyo’s visualization and realized it didn’t match the reality of interacting with LLMs. His corrections tackled both of my qualms with such simplicity that his figures suffice to visually understand what my qualms are. (When I saw Pueyo’s tweet, I immediately realized it was wrong, but then I saw Fraser’s correction; he beat me to it.)

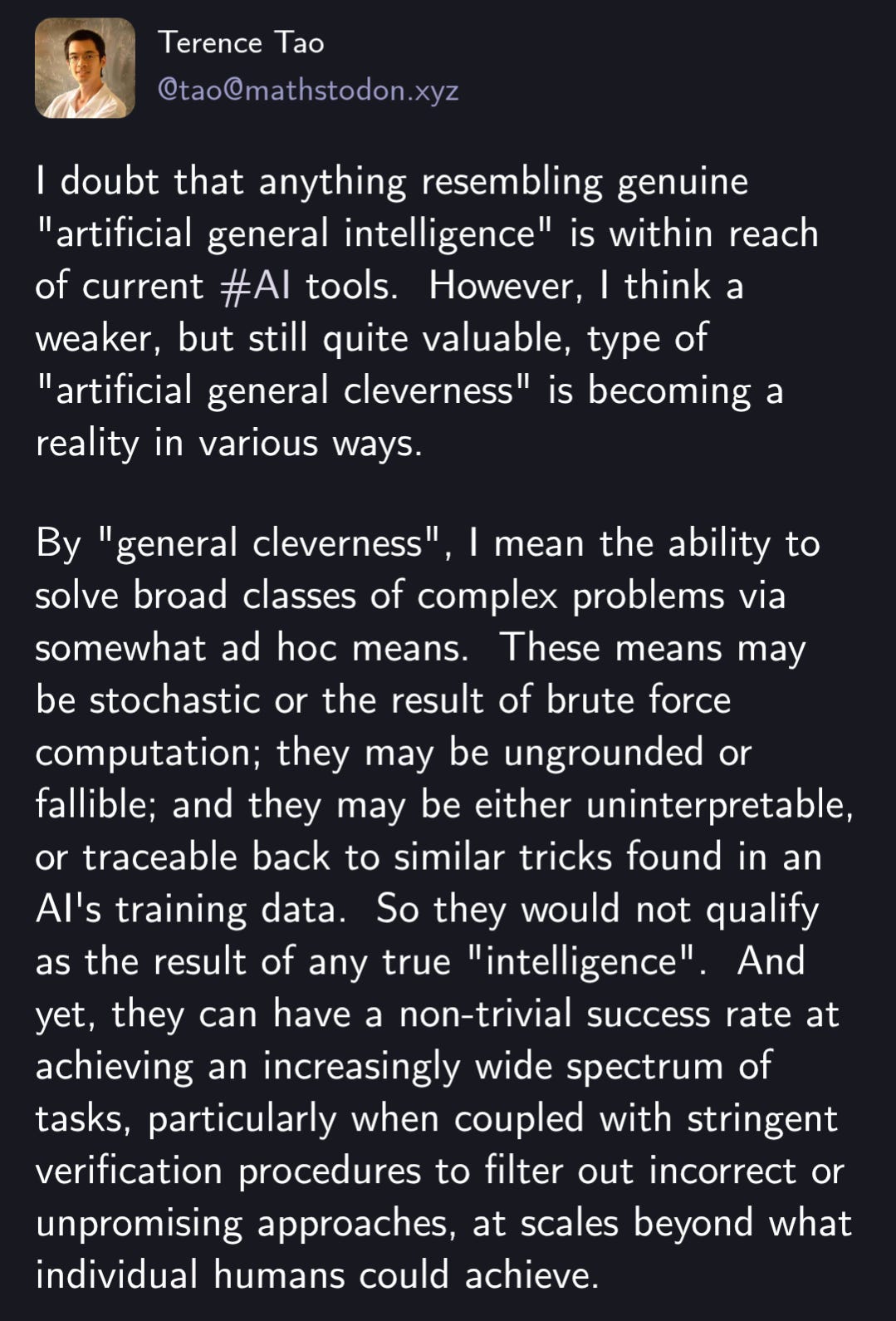

Basically, what Fraser argues is that working with a cutting-edge LLM like Gemini 3 or Claude 4.5 doesn’t feel like interacting with a big pink blob of overwhelming intelligence that covers everything around you except some spots. You feel like you are interacting with an alien savant (they’re more “clever” than “intelligent,” to use mathematician Terence Tao’s most recent description).

I love Tao’s distinction between “intelligence” and “cleverness” because it cuts through the confusion that people have that non-intelligence in the human sense implies uselessness. That is so untrue that it’s better to simply say back: “Ok, no, AI is intelligent.” However, that’s also quite wrong in the exact sense Tao argues above. I truly hope this disambiguation catches on.

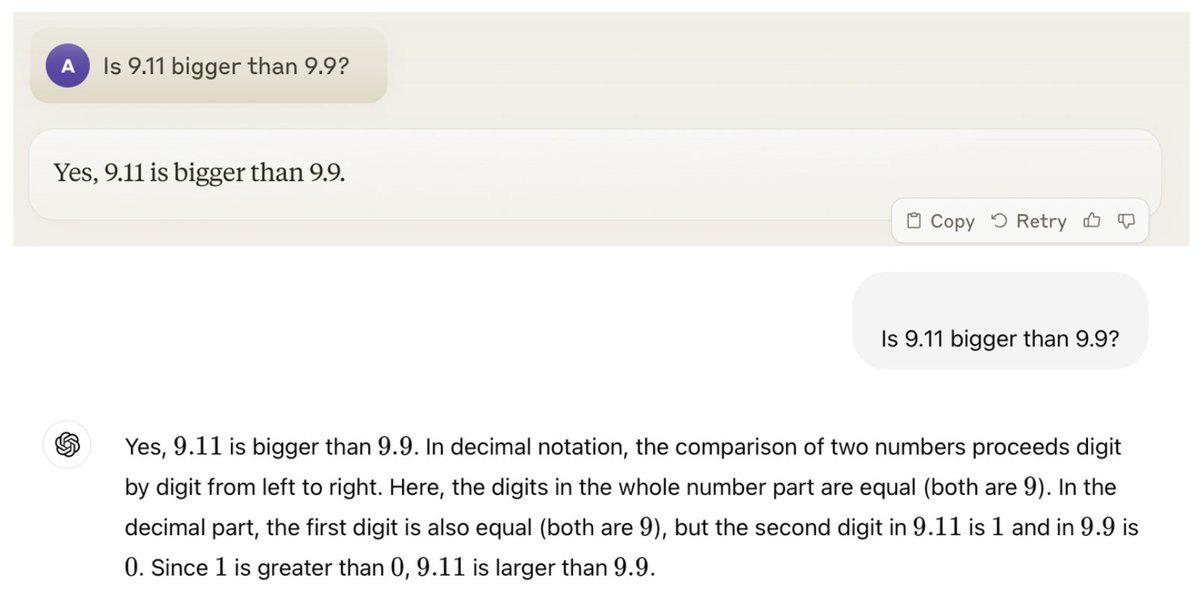

Here are some examples that reveal how extreme the jaggedness is and how surprising it is that AI is still unable to solve simple puzzles whereas it can solve extremely hard problems: the AI can write a perfect sonnet about quantum physics (a creative spike) or distinguish virtually similar dog breeds (a perceptual spike), but it might fail to tell you how many r’s are in the word “stawberry” (tricky, I knlw) or h’s in the word “honeycomb” (a surprising gap), or whether 9.11 is smaller or not than 9.9 (another surprising gap).

On this basis, Fraser refined Pueyo’s visualization (I like Pueyo’s asymmetry more because it better resembles the fact that AI doesn’t get better to the same degree at the things it’s already good at, but I understand Fraser’s emphasis is not in symmetry but in the extreme jaggedness that doesn’t quite cover the human circle regardless of how much we improve the things AI is already good at):

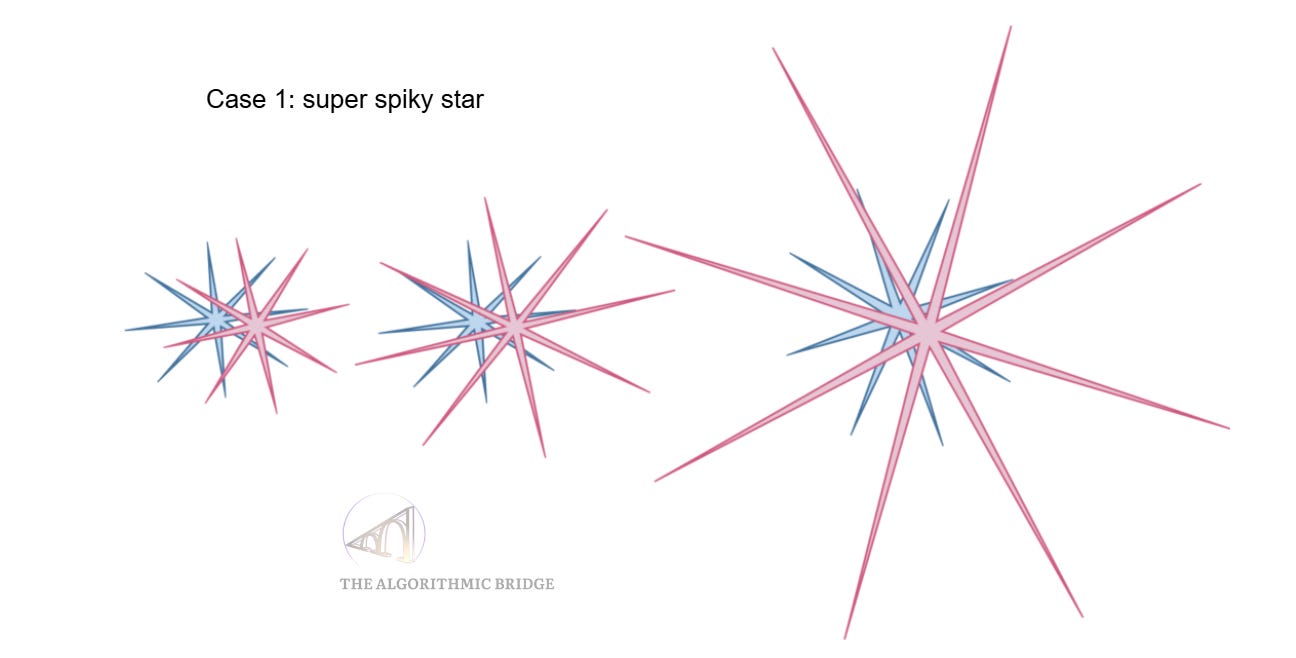

Here, the AI is not a blob but a spiky star, and the “jaggedness” is not so much a fleeting texture contingent on our imperfect methods and AI training regimes that will eventually disappear into an ocean of supremacy, but the fundamental structure of the entity. This correction addresses my second qualm with Pueyo’s visuals. As the models scale, the spikes get longer. The AI gets better at the things it is already good at (making calculations and finding patterns in data), but not necessarily better at the things it’s been terrible at for so damn long!

Notice what happens to the center of the star. It doesn’t expand at the same rate as the spikes. The gaps between the spikes—the “valleys” of incompetence—remain deep. This explains why an AI can pass the Bar Exam (a massive spike in retrieving and organizing legal text) or get gold in the International Math Olympiad (a massive spike in solving problems for which verifiable rewards exist) but still struggles to reason through a common-sense physical problem that isn’t in its training data (a deep valley) or ARC-AGI 2 and 3. This is what I described with this counterintuitive maxim: “It’s trivial to raise the ceiling of capabilities but hard to raise the floor.” (I first mentioned it in my articles on GPT-5.)

If this conceptualization is correct, AGI might be “geometrically impossible.” You can make the spikes infinitely long, but you can never force a star to become a circle. There will always be slices of the blue human domain that the AI simply cannot touch. However, it is not correct. At the very least, it is incomplete. Here’s how Fraser handled my first qualm, the human circle.

The “spiky star” representation of AI assumes that the human domain is the perfect, Platonic circle against which all other intelligences are measured. We look at the blue circle and think, “That is what general intelligence looks like, a perfect circle of human superiority.” But why? We think human intelligence is general only because we are humans. We define the circle by the things we can do. We intuitively define “intelligence” as “the set of tasks humans have evolved to solve.” That’s Fraser’s final proposal: the human shape is not a circle; we are also a spiky star. (The star shape itself is not important; the idea is that whatever we’re good at is not a perfect shape but defined by our evolutionary constraints. You can imagine a random shape of any kind you want, but a star is simpler to visualize.)

This entire exchange between Fraser and Pueyo happened in the span of three tweets, so it’s fair to think that the chain of insights isn’t profound, but it is. It has deep roots in biology and philosophy, and implications for the future.

IV. A world of one’s own

In the early 20th century, zoologist Jakob von Uexküll coined the term Umwelt (self-world). He argued that every organism exists in its own sensory bubble, defined by what it can perceive and act upon. The world has a circular shape, insofar as it is perceived by a being that can interpret it as having that particular shape; otherwise—from an “objective” point of view—it is spiky.

Our star-shaped territory is defined by our Umwelt. Our spikes are determined by our evolutionary history. We have a massive spike for social intuition, for reading facial expressions, for maneuvering objects in 3D space, and for understanding causality. We have deep valleys where we are terrible: we are bad at probability, we have terrible working memory, and we are slow at arithmetic. A tick’s Umwelt (a typical example) is defined by the smell of butyric acid, the warmth of mammalian blood, and hairiness. If a bat were writing this article—a creature philosopher Thomas Nagel famously used to illustrate the inaccessibility of other minds in his landmark paper What Is It Like to Be a Bat?—the spiky star shape, the Umwelt, would center on echolocation and 3D aerial navigation. From the bat’s perspective, humans would look like a jagged, incompetent mess because we keep walking into walls in the dark.

The capability/intelligence territory of all creatures is shaped like circles from their point of view—their Umwelt, their evolution—and, at the same time, shaped as weird stars from the objective point of view of the universe.

Philosopher of science Peter Godfrey-Smith explores this further in Other Minds, looking at the octopus. The octopus represents a “second experiment” in the evolution of intelligence (a third could be corvids, although they share more features with us, great apes, than octopi): a mind built on an entirely different plan from vertebrates, with neurons distributed through its tentacles, three hearts, and soft, gelatinous tissue.

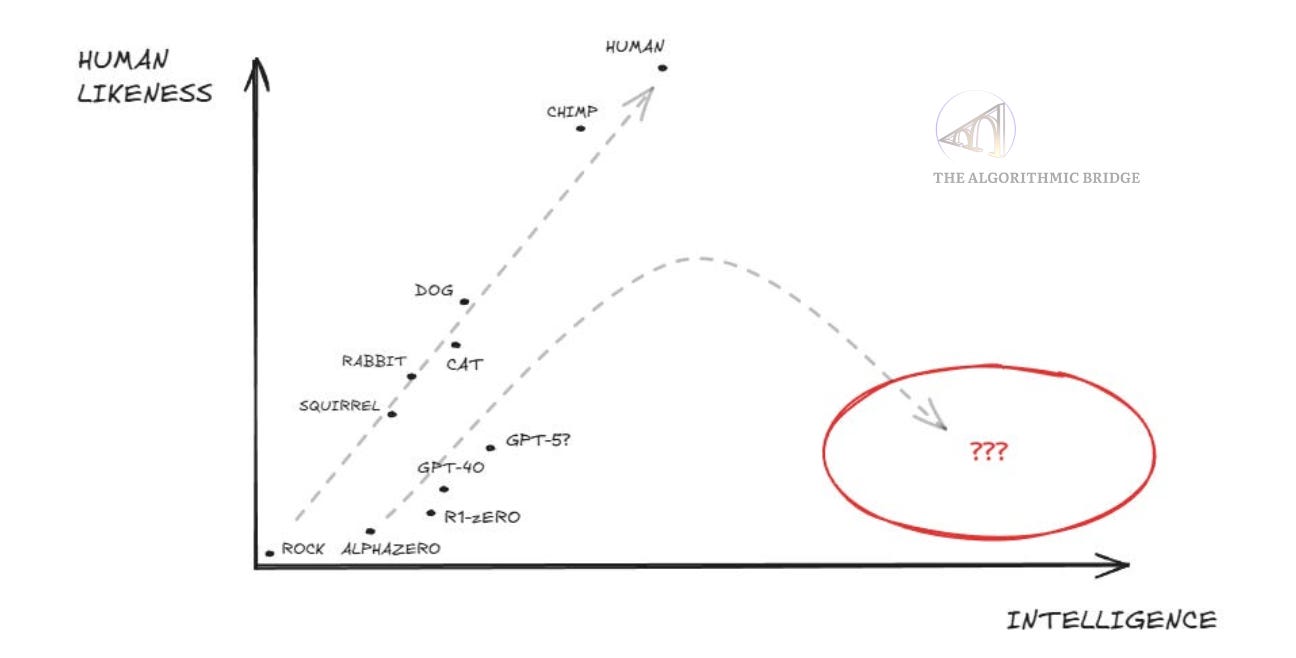

But even the octopus or the tick—evolutionarily distant as they are, one smart, the other dumb—are still our cousins. They eat, mate, die. They are carbon-based. AI is a species so distinct that it makes the octopus look like a second cousin once removed; an oval to our circle. We squabble over differences with other humans who are 99% genetically identical to us without realizing that we are interacting daily with an entity that is perhaps 1% similar to us (it was trained on the corpus of human text, so it’d be an exaggeration to say 0.01% or something), yet comparably intelligent. I drew a relevant graph on “human likeness” vs “intelligence” for AI Is Learning to Reason. Humans May Be Holding It Back, an essay that didn’t get much attention:

The “human star” is just one possible shape of intelligence; it is not the master template. Why are we surprised when AI happens to be so distinct, so alien in its failure modes? There’s a quote often misattributed to Einstein that gets to the gist: “Everyone is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.” When you ask Gemini 3 to solve a high school math problem or write a Shakespearean Sonnet, you’re asking a monkey to climb the tree. When you ask ChatGPT to solve the games on ARC-AGI 3—you can tell it is my new favorite AI benchmark—or wash your clothes, you’re asking a fish to climb a tree.

This is the essence of the jaggedness. We are judging the AI by its ability to fill our human shape. (We do that because we can’t avoid anthropomorphism, which is, itself, a gap in our spiky intelligence, like other cognitive biases that distance us from an objectively perfect circle.) When we realize that all shapes are jagged stars, we accept that the goal of AI development is not to create a circle that covers the human shape but to overlay two complex, spiky shapes or, failing that, to grow the AI star shape as much as possible. This approach leads to three scenarios that will coexist:

Where the spikes overlap, we have replacement: AI can do what we do.

Where the AI spike extends into our valleys, we have augmentation: AI does what we are bad at.

Where our spike extends into the AI’s valleys, we have the “human in the loop”: we provide the common sense and intent that the machine lacks.

So far, the vast majority of real-world tasks or problems fall, invariably, into the second or third cases. The reason is twofold:

First, there’s hardly any pre-training data online that can give AI models a general sense of what they need to know to solve real-world problems. Besides, the conditioning process needs verifiable rewards, and you can’t have them for everything because tacit knowledge can’t be made explicit: the know-how of masters can’t be formalized with language; you don’t learn to ride a bike by reading a “how to ride a bike guide” with all the steps, but by riding a bike.

Second, any given task is often complex enough that you won’t find a way to fit it into the first case. Unless you subdivide each problem many times down to its elemental constituents (prohibitively slow and often unfeasible), you will be faced with a situation that’s a mix of the second and third cases: the AI will do part of it, and you will do part of it.

In most cases, not even simulation environments are enough because the physics of the real world are computationally irreducible: you can’t make a model of the real world and expect a system trained on that model to be able to solve all scenarios and situations it might encounter in the wild. That’s also why self-driving cars are taking much longer than originally expected (at times they’re better than the best human, but other times, they make mistakes the average human wouldn’t make).

The thing is, our world, our beloved real world that we share with all these things—the tick, the bat, the octopus, the AI—also has a shape. To a large degree made by us, to our likeness, designed to fulfill our needs and adapt to our capabilities, it looks suspiciously similar to an Umwelt manufactured for us (not quite, though, for we live straddling a natural world for which we evolved, but which has not yet disappeared, and a cultural-technological world that we have created, but to which we have not yet fully adapted):

You can support my work by sharing or subscribing here:

V. From star to supernova

What’s going on? Why are the shapes so different? Why doesn’t the AI simply grow into our shape? The answer lies in how our intelligences are formed. They’re the products of two different optimization processes (this difference is pretty much fixed because the first process you can’t revert, and can’t make the other a copy of the first).

Human intelligence is the result of biological evolution. Our neural nets were optimized over millions of years for the survival of a tribe in the jungle. Every capability we have—from language to tool use to face recognition—is a byproduct of the pressure to survive, reproduce, and navigate social hierarchies. Our “spikes” are survival mechanisms. We are efficiently intelligent because every evolutionary mutation that could have sent us down a less efficient path would be a doom from the standpoint of natural selection. The human brain runs on about 20 watts. It has to.

AI intelligence is the result of mathematical optimization. It does not care about 20 watts (nor do the companies selling it). Andrej Karpathy, one of the leading minds in AI, recently articulated this distinction perfectly in his review of 2025. He noted, as he has already said a few times elsewhere, that we aren’t “growing animals” in a lab; we are “summoning ghosts.” (He featured Fraser’s visualization, which itself inspired this article.):

2025 is where I . . . first started to internalize the “shape” of LLM intelligence . . . We’re not “evolving/growing animals”, we are “summoning ghosts”. Everything about the LLM stack is different (neural architecture, training data, training algorithms, and especially optimization pressure) so it should be no surprise that we are getting very different entities in the intelligence space.

Indeed, Geoffrey Hinton, the Godfather of AI and Nobel Laureate, had an epiphany last year that parallels this view (I covered it in We’re Not Ready For the Aliens to Come, where I featured octopi as well). For fifty years, he believed that to build better AI, we had to mimic the brain. But he eventually realized that digital intelligences might be a better form of intelligence—one that can pack far more knowledge into fewer weights—but one that could never evolve biologically because it is too energy-intensive. It needed us to create it.

Capitalism is the new evolution for these entities. An AI system can be energy-intensive and still survive, as long as it pleases shareholder selection. We can create intelligences that burn gigawatts to solve problems, taking the best from nature (the neural net structure) and leaving the flaws (the constraints of biology).m This is why the AI shape is so weird. It is a “genius polymath” because it has read the entire internet. But it is also a “cognitively challenged grade schooler” because it has never had to survive a day in the physical world. It lacks a core of self-preservation or a consistent identity. It is a collection of statistical probabilities loosely held together by a prompt you come up with in five seconds.

Karpathy points out that as we use techniques like RLVR (Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards), we are artificially pulling on certain spikes. If we train a model specifically to solve math puzzles (where the answer is verifiable), we get a massive spike in math capability. The star stretches out in that direction. But that doesn’t mean the core of the star has grown. The model hasn’t become “smarter” in a general sense; it has just been overfit to a specific domain. It becomes a savant in that narrow corridor, while remaining brittle everywhere else; more “clever” than “intelligent.”

These distinct optimization processes entail a crucial nuance that breaks an otherwise perfect geometrical parallelism (one that might bring us back to Pueyo’s take): velocity.

The human star is biologically static. Evolution works on geological timescales. The brain of a 21st-century AI researcher is structurally identical to that of a hunter-gatherer from 50,000 years ago. We have better software (culture, education), but our hardware—the core processing unit—is frozen in time. In contrast, the AI star is expanding explosively. Researchers are constantly iterating on the layers beneath the surface—improving the post-training process, improving the data filtering and data generation, trying new architectures and hyperparameter tuning, testing neurosymbolic approaches… Karpathy’s ghost is being summoned into better vessels every few months.

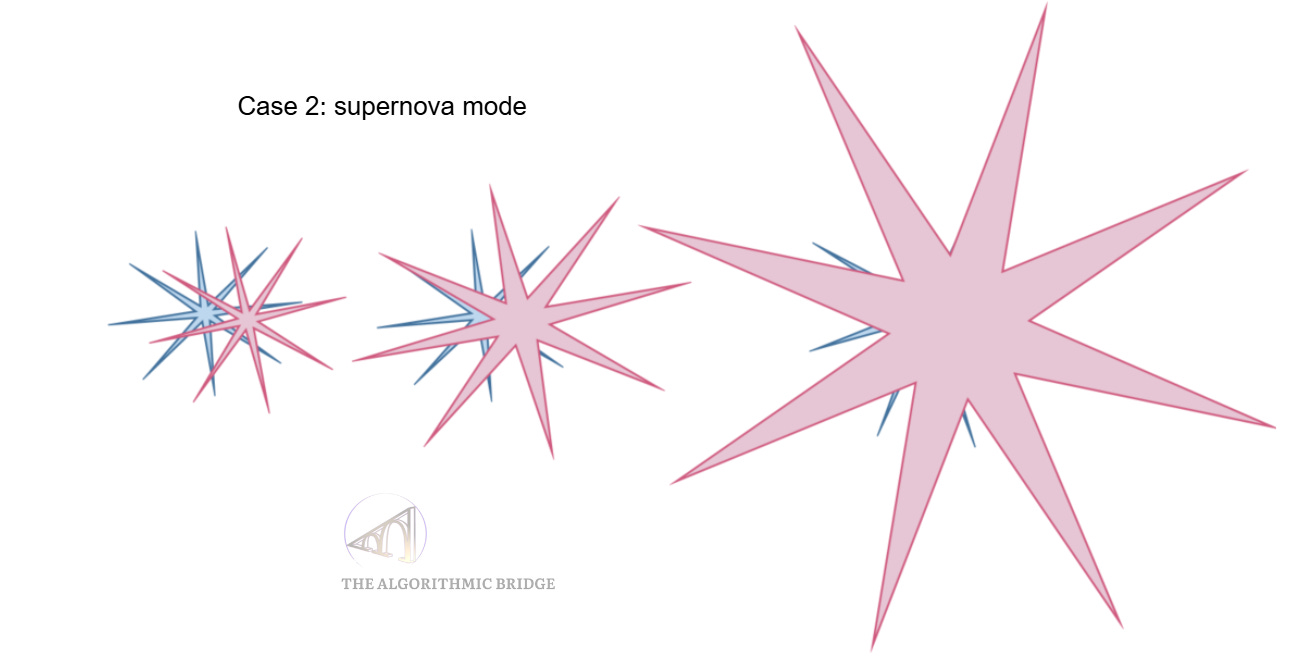

This suggests that while the star shapes are currently overlaid on distinct intelligence territory, the AI star is growing fast enough that it could eventually swallow the human one entirely. (If we eventually grant AI a body, senses, and a modeled form of consciousness, it may begin to conquer even the most intimate human territories: thinking about oneself, feeling, or loving.) There are two possibilities from here (Fraser doesn’t extend his visualization this far):

The first case is an extension of “raising the ceiling but not the floor of capabilities.” Maybe the floor will never rise to human level; maybe hallucinations and unreliability are intrinsic to the current batch of AI models and will require a substantial overhaul of how the field is doing things right now. The second case is just another version of Pueyo’s picture: If AI grows its core skills, it might completely cover what we call “human-level” intelligence in a supernova-like explosion of capabilities (this is the case of full replacement).

(Note that, if we take into account Fraser’s insight (as well as Karpathy’s comments, Ilya’s remarks on Dwarkesh podcast, Yann LeCun’s move from Meta, etc.), this case is not meant to happen over the next months but rather over the next years or even decades (if ever).)

If we’d wanted to push this conceptualization further, we could argue that humans are also expanding their core through tools. A human with a smartphone or a hammer is “smarter” than a hunter-gatherer. But this applies better to humanity as a collective super-organism, not the individual biological unit (I don’t know how to build a hammer or how to use a hammer to build a skyscraper).

In parallel, we are witnessing the birth of a similar collective in silicon. It isn’t just one model; it is the aggregation of all agents, instances, and data centers. We might call this “synthelligencity,” a portmanteau of synthetic, intelligence, and city. (Not easy to find an analogy to “humanity”!)

This reflects the vision of Jesuit philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who in the mid-20th century predicted the emergence of the Noosphere, a global, thinking layer of distributed interconnected consciousness wrapping the Earth. Synthelligencity is the silicon realization of the Noosphere, a sprawling metropolis of cognitive ability growing at a rate biology cannot match and in a shape it won’t imitate. (Maybe humans and AIs could co-exist as different biomes in the same Noosphere, but maybe we naturally diverge, like the OS in Her. It’s just impossible to predict at this point.)

Google DeepMind scientists proposed this formally in a paper on AI safety published this month, where they argue that we should focus more on the possibility that AGI could emerge “through coordination in groups of sub-AGI individual agents with complementary skills and affordances.”

VI. Final thoughts: It’s ok to move the goalposts

I close with this. For years, critics have accused skeptics of “moving the goalposts.” Every time AI clears some milestone (games, perception, coding), they redefine intelligence to exclude it. “That’s not real thinking,” they say. On this point, Dwarkesh Patel said something few dare say in public:

. . . some amount of goal post shifting is justified. If you showed me Gemini 3 in 2020, I would have been certain that it could automate half of knowledge work. We keep solving what we thought were the sufficient bottlenecks to AGI (general understanding, few shot learning, reasoning), and yet we still don’t have AGI (defined as, say, being able to completely automate 95% of knowledge work jobs).

As he argues right after, maybe our current AGI definitions are “too narrow” (the official definitions, at least, there are outliers who will proudly say they don’t think AGI is anywhere near). If this implies we need to move the goalposts, so be it. If the jaggedness of AI proves to be too accentuated, the AI community will have no other option. We do, though. Investor Naval Ravikant (at least I think he said it first) flipped the idea on its head: “It’s not so much people moving the goalposts on what an AI is, it’s more AI moving the goalposts on what a human is.” I find this approach more useful for everyday life and for the average person.

The premise is that we are not ready for this. We think ideology and religion are unbridgeable gaps, but that’s because we haven’t yet faced true otherness. We are about to (try to) co-exist with a mind that shares none of our biological history, none of our energy constraints, and none of our emotional fragility; a distant star like those in the night’s firmament. This is a new species of being. As the AI star of capabilities expands, conquering the territories we thought were exclusively ours, we will have to find spiritual shelter somewhere else.

In his 1961 classic Solaris, Stanisław Lem wrote: “We have no need for other worlds. We need mirrors.” For decades, we looked at AI wanting it to be a mirror reflecting us, but twice as large, as Virginia Woolf wrote in A Room of One’s Own: “Women have served all these centuries as looking glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size.” Now it’s AI instead of women, and the object to be reflected twice as large is all humans, men and women alike. However, instead of a mirror, we found a spiky-shaped thing we cannot fully grasp. Let us move the goalposts of being human; let us embrace the weird.

The utility of AI in the coming decade won’t come from it replacing the human circle because there’s no such circle. It will come from us learning its geometry, and learning where its spikes are strong enough to carry the load (augmentation, partial replacement), and where its valleys are deep enough for us to continue being the architects of the world (the human-in-the-loop). Full replacement is, on this account, unlikely in the short term, for we are not climbing a tree with a fish or a monkey but dancing with a star.

So rich in thoughts. Thanks.

Our confrontations/friendships/collaborations with these aliens is indeed forcing us to rethink what it is to be human and what we value about being human. Our species' foundational experiences of what it means to be alive are changing, and will probably keep changing as you suggest for many decades to come.

The result will be something new, something different from the humans we have been since we became Homo sapiens. I call this transformation a fourth revolution in consciousness, but the label hardly matters in the face of the turmoil sure to come.

“What’s going on? Why are the shapes so different? Why doesn’t the AI simply grow into our shape? The answer lies in how our intelligences are formed. They’re the products of two different optimization processes (this difference is pretty much fixed because the first process you can’t revert, and can’t make the other a copy of the first).”

excellent. really likes this section of your breakdown here. thanks for the post. also great engagement in the comments!