As AI Gets Better I’m Less Worried About Losing My Job

One simple reason

I was told AI would take the world by storm, but I looked out the window just now and the sun was shining like any other early September morning in Spain’s south; the gentle waves of the Mar Menor softly caressing the shore, and the loud cicadas reminding me of the heat and the sweat and that I actually hate Summer.

That’s a joke about how hard it is to make accurate predictions—weather or otherwise—and a revelation: it doesn't matter what the internet zeitgeist preaches, the real world goes on immutable, unapologetically indifferent. But it is also a confession: I can take AI’s threat to my job nonchalantly because I was never particularly worried about losing it in the first place, neither before nor after the inception of its generative branch, presented by popular outlets as this unknown force that, erratic like a tornado and devastating like a flood, would bring about hell on Earth (at least to those places where hell is not a daily occurrence).

Call me over-confident or maybe reckless, but that was my genuine sensation: there's an “it” about writing well that's qualitatively different from just writing; if ChatGPT is proof of anything, it's that somehow, reading the entire corpus of human literature is not enough. It might be a great tool for narrative analyses, but it's terrible at manifesting its erudite insights into a masterpiece. I don't want to offend anyone, but I've come to see AI, as far as its writing skills are concerned, like a frustrated editor or maybe a professional critic: good enough to detect genius but not good enough to be genius itself.

In post after post, I tried to rationalize why, as an unknown writer, I felt safe despite my familiarity with AI’s relentless conquest of formerly human-exclusive domains, like chess or pathological flattery. But of course, being a devoted user of AI myself, with each iteration I saw the models grow better at everything except at crafting decent fiction (or poetry or plays or non-fiction essays, for that matter). There's a case to be made that it actually got worse! I nevertheless failed to figure out why AI finds it harder to write a memorable line—that is, besides “bottomless pit supervisor”—than winning the gold medal on the International Math Olympiad.

The best I got was: 1) companies don't care about writing because, unlike coding or math, it doesn't get them a better model down the line and so they're not aiming for ChatGPT to write the next great American novel; 2) beyond some level, writing finesse lies in the eye of the beholder, so how good a writer is is a thoroughly subjective matter, which is the kind you don’t standardize; 3) Moravec's Paradox strikes again: things we think easy are hard for AI and vice versa; 4) unlike chess, which is a narrow + deep domain, writing is a broad + deep domain: mastering it requires many skills, not just putting words one after another; and 5) writing, the craft I chose, is singular in the infinite pool of crafts I could have chosen from—which is chauvinistic in a way I like personally but not as an explanation.

And so without answers but also without concerns, I checked the weather every day for three long years by inertia or perhaps instinct, like someone does when they have no real intention to go out or otherwise plenty of handcrafted umbrellas waiting to be opened for the first time; out of routine but largely untroubled by anxieties that would wreck most people's sleep. Today, I see vindicated my composure. I'm making 10 times more money from my writing than I was when ChatGPT came out (I’m not rich; I was making so little back then). And although there's plenty of slop on social media and platforms like Substack and Medium—not going to deny the decaying of the ecosystem writ large—I've yet to see any shrinkage on my audience or my career prospect for AI-related reasons.

Indeed, as far as good weather goes, this state of affairs is not exclusive to craft-obsessed writers; talking to my older brother—he’s a senior developer, enthusiastic about AI, and lurks the same online circles I do—we agreed that we are both less worried about losing our jobs than we were three years ago. Time was always AI's enemy; whether it’d take our jobs was an increasingly less likely possibility each day it didn't, because it implied neither global adoption, nor careful workflow integration, nor sheer benchmark performance were enough for it to topple humanity’s creative hegemony. And thus, here I stand, three years later, undefeated.

But I'd be doing a disservice to college students, who may be reading these words with unwarranted hope, if I finished my story here. For I am safe because I am not new; I am safe insofar as the time I've been writing has yielded some measurable expertise that grants me a sort of escape velocity. I used to feel safe because I thought writing well was itself out of reach for AI (not clear yet whether that's true); I feel safe today because I started early, because I happen to exist beyond the event horizon; because the growing AI-powered competition has settled, like cold air from the air conditioning machine in a hot summer or water in a water-oil mixture, below some indefinite threshold that will impact most severely those starting out, which isn’t me but might be you. College grads and overall junior types, with their beardless faces and immature agency, should be worried about their jobs and professional career options. It was never a matter of AI not being good enough to do my job or writing being divinely anointed as this sacred out-of-reach territory, but a matter of lucky timing.

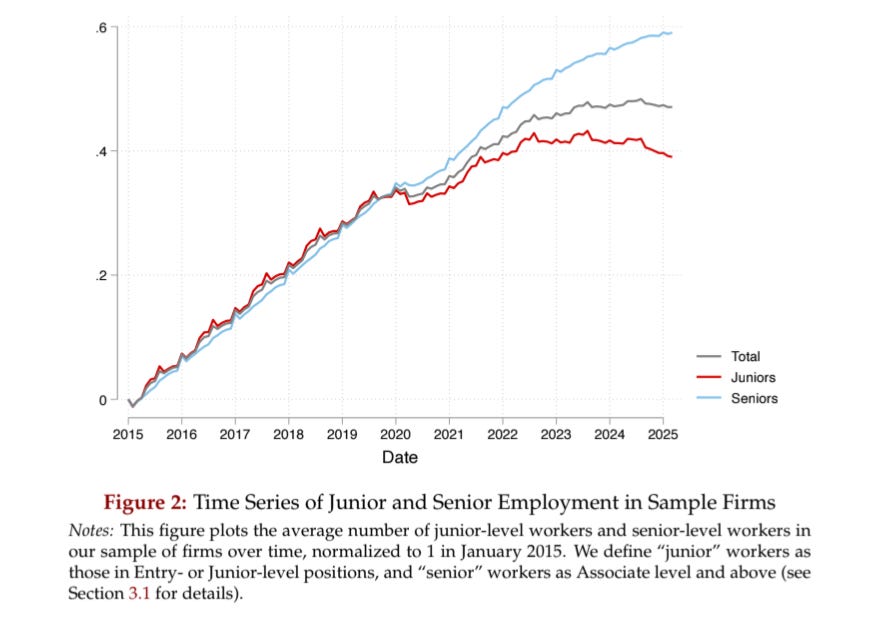

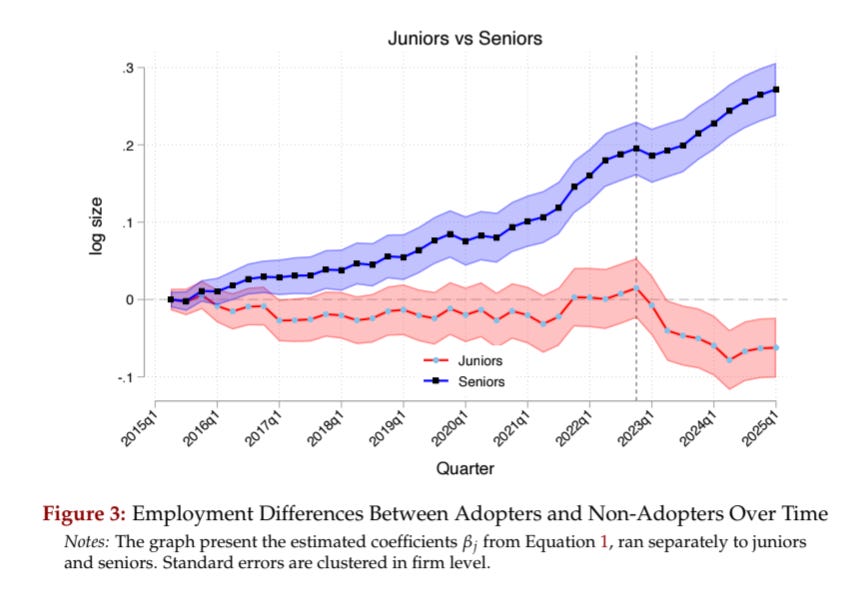

Ethan Mollick, who also writes, who is also deeply interested in AI, and who is also safe from its threats as a professor at Wharton and a popular newsletter author, recently shared a preliminary paper about AI’s effect on jobs titled “Generative AI as Seniority-Biased Technological Change.” (He's shared a few peer-reviewed studies on the topic over the past months, but I will focus on this because it's the latest one in a streak reaching the same findings.) Take a look at the figures below (285,000 firms, 2015-2025 period). The first chart measures total junior-senior employment across time and the second, junior and senior employment comparison between AI adopter and non-adopter firms across time. What do you see?

From 2015 to 2022, there's nothing alarming going on, just the usual hardships for kids entering the labor market for the first time, until in mid-2022 junior employment starts decreasing significantly, especially for companies adopting AI.

If we are to believe these numbers—and I kinda do—AI’s threat to the junior-tier office-job white-collar workforce is hardly a matter of weather forecasting anymore but of empirical evidence. What was three years ago the manifestation of my on-brand arrogance as an essay writer, is today a solid statistical pattern: whereas senior roles are keeping their jobs—and actually more in demand than ever—junior roles are on the line. These results match my intuition so well that I'm probably doing hindsight revisionism; maybe I was a little more worried when I was getting started than I'm letting on. It played out for me in the end; had I listened to that soft warning, I may not have put in the work that pushed me beyond the blast radius.

Not everyone agrees with this interpretation, though. For instance, economics blogger Noah Smith, a long-time “AI will take our jobs” denier (his arguments are valid, in the form of ”AI takes over tasks not jobs,” “comparative advantage will save humans,” etc.) looked at this line of research (as far as I know, not this paper specifically), and went: “ok, the data suggests I might be wrong but have you considered how [some biased scenario] makes no sense? And also, isn't it obvious that [some personal intuition] is true??” It's hard to establish causal explanations for hiring dynamics and AI is definitely not the entire picture—although the paper I cited explicitly separates companies doing AI adoption from those restraining from it, which suggests the effects you see on those charts are at least indirectly a consequence of AI—but plenty of recent evidence suggests it's people like Noah Smith who now carry the burden of counter-argument. Interestingly, he ends the post saying, “. . . experience is a complement to what AI can do, while formal education (which is all young workers have) is a substitute.” Isn’t that exactly the problem?

Now I could take this essay in two directions: 1) what I’d do if I were a junior would-be writer and 2) the social-level implications of not hiring junior roles in favor of AI, which will become apparent once senior roles retire and companies realize that AI can't replace them—nor do juniors who never learned the know-how that you only acquire directly from those who know more than you, who are now growing apples and blueberries in some countryside orchard in New Hampshire.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Algorithmic Bridge to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.