Why There Are No AI Masterpieces

So much for having scoured the entire web

I.

Nando de Freitas, ex-Google DeepMind, now at Microsoft, asks an important question:

AI has generated tons of text, billions of images, video and songs. I feel however it has never generated a song worth listening, a book worth reading or a movie worth watching. Why?

This is the artistic analogue to the scientific conundrum that keeps podcaster Dwarkesh Patel awake at night (asking Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei here):

What do you make of the fact that these things have basically the entire corpus of human knowledge memorized and they haven't been able to make a single new connection that has led to a discovery?

Both deserve deep inquiry (Google DeepMind may have solved the latter; will publish a write-up on AlphaEvolve soon), but I will restrain myself to the artistic version here, for I tend to be a bit of a dilettante. Alberto, remember: one idea at a time!

I believe the answer has a lot to do with the fact that few things created by humans with artsy aspirations are worth anything in isolation. Their worth comes from what surrounds them, from the human context that birthed them and the human lives that were impacted by them. That's how masterpieces are judged as such.

Scientist and blogger Adam Mastroianni talks about this fundamental element of art in his “28 slightly rude notes on writing” (in points 14, 15, 20, and 21). “Maybe that’s my problem with AI-generated prose:” he says, “it’s all necklace, no neck.” I don’t think you need the full reference to understand what he means, but just in case:

Some people think that writing is merely the process of picking the right words and putting them in the right order, like stringing beads onto a necklace. . . . The beauty ain’t in the necklace. It’s in the neck.

The neck is the context that gives the necklace its raison d'être.

And he adds:

[AI-generated prose] has no context—or, really, it has infinite context, because the context for its outputs is every word ever written.

It's not just the existence of context that matters, but its specificity. Things are only to the extent that they are not other things. That’s why writing about the smallest thing is much more powerful than trying to encompass the entire universe in an essay. You end up being nothing when you try to be everything.

Moreover, the context doesn’t need to be historical or personal, even materialistic differences matter. Journalist Max Read of Read Max—such nominative determinism—expands on this point in response to Scott Alexander’s AI art Turing Test. He says,

. . . the materiality of painting is not some accident of its being; its form, its texture, its size, etc. all carry with them meaning and effect.

I agree with both Adam and Max.

II.

Let's take one of the most famous paintings ever made: Pablo Picasso's Guernica.

So here's the big question:

What do you think would be your first reaction if Picasso had painted the Guernica in secret and decided to never tell the world and abandoned the painting in the middle of a forest and then, eighty years later, during your routine morning hike, you found it standing there, behind some big pine—dusty, yet as wonderful and ominous as it looks today, hung in the Museo Reina Sofía?

Do you think you'd admire its profound reflection of a human tragedy? Or you'd perhaps notice the subtle brush strokes and the deconstructed style? What about the people in apparent agony and the black and white tonalities? Perhaps the texture or the size? Or, conversely, you'd ask yourself:

What the hell is happening here?

Where did it come from?

Who created it?

What story inspired it?

What’s the neck for this necklace?

You would seek, first and foremost, the context. Because neither the name “Guernica” nor the giant canvas would mean much to you had Picasso kept it a secret (unless you’re a Spanish Civil War historian, that is).

In the case of AI, all of that context is not inaccessible but nonexistent. (Or, like Adam says, infinitely generic.) There are no questions to ask the AI about whatever painting it makes. It can have some impact on people, though; I Ghibli-ified my girlfriend and she liked it. Is that enough to call something a masterpiece? Perhaps not.

But I have a counterpoint in favor of the AIs (in case they read this): I’m limiting the analysis to art itself, but what about art that's about art?

The meta art.

III.

The times I’ve seen something made by AI that I thought “ok, that's good” have been when the art emerges at the meta level. That's when you go: “look what this AI model did and how it affects the cultural zeitgeist,” instead of just “look how good this is.”

It is only in this art-is-also-created-when-something-incites-us-to-talk-about-art sense that the product of AI has some resemblance to human context—the existence of AI itself is a historical event sufficient for this—and thus could eventually be judged as a masterpiece.

One example is the image that X user “DonnelVillager” created from Keith Haring’s Unfinished Painting (below the original and the AI-generated version):

In “Toward a shallower future,” economics blogger Noah Smith comments on the (understandable) backlash of art appreciators at the AI version and why DonnelVillager's prank can be considered a work of art itself:

DonnelVillager’s post—perfectly calculated to simulate ingenuousness, while actually poking fun at art appreciators—was itself a masterwork of internet pranksterism. It was instantly condemned by tens of thousands of angry Twitter users for “desecrating” Haring’s art. Defenders responded that DonnelVillager’s trollish tweet was itself a work of art, and that the furious response proved that AI art has the potential to be transgressive and to tweak the cultural orthodoxy’s tail.

People got mad, but more at the affront (clearly ragebait) from the prompter for insinuating that a machine could finish the work than at the work itself. That’s art—both the prank and the image—even if solely of the annoying kind.

Unfinished Painting is an especially interesting case because it is already a form of human meta art: what’s beautiful is not the painting but its absence. The canvas being left unpainted reflects that death reaches us all, sometimes tragically, and sometimes suddenly. The AI-finished version is, thus, a rare example of meta-meta art.

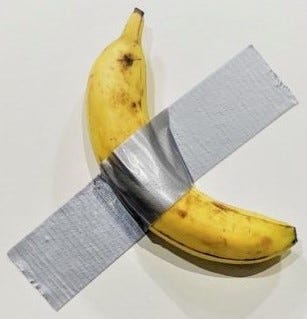

But I don't want to overcomplicate the argument with too much meta, so let's take a simpler example. Like this image:

It would be cool if a human had made it, but no more than that. Cool is not the adjective you use to describe a masterpiece. Good taste keeps me from superlativizing the qualifier—it’s just not that good.

But, at the time this went viral, once you realized it was made by an AI, you understood you were not looking at the artistic decision of a human painter but a specific method for achieving this superposition of shape (a spiral) and landscape (a medieval Mediterranean village). That’s perhaps more than cool. It’s surprising. It’s novelty. It's the creativity of the technique that deserves praise as art and could be, if perhaps done better than this, judged as a masterpiece.

Nonetheless, M. C. Escher was already playing with shapes and landscapes and the defiance of physics that only the artist dares make manifest half a century ago. His art—below Waterfall, 1961—is more impressive and captivating than this anonymous AI-generated piece.

No AI, no nothing except pure imaginativeness. A neck so special that no necklace could make it prettier.

So humans win again, saved, as always, by the best among us.

Or do we?

IV.

Despite everything I’ve said in favor of my preferred tribe—humans—I do believe someone will eventually create an AI masterpiece. Here’s how I think we’ll come to accept what now feels almost blasphemous to even suggest.

Some human artists—the ostracized, the open-minded, the best among us, as judged by distant future generations—will lean on AI (they have already). They will attempt to make something unique in itself, not trying to be human art, but as a contrast to it. They will escape forward, embracing an untapped world of creativity.

At first, all interesting attempts will indeed fall into the meta category of “this is worth it insofar as it presents some opposition to human art.” Humans themselves have done that in the past; duct-taped a banana to a wall (Comedian by Maurizio Cattelan) or exhibited a physical urinal (Fountain by Marcel Duchamp). The main difference is that in the case of AI, the context wouldn’t be just historically meta-artistic but also technologically meta-artistic.

But eventually, artists focused on AI will need to grow beyond meta art, like they grew beyond mimicry. For one simple reason: meta art has a short shelf life. Once you make the meta popular, it stops being valuable as meta and becomes the norm. If you start to use AI to finish all unfinished paintings or repeat that mesh of shape and landscape for all landscapes and shapes, or Ghiblify the entire internet, it gets boring.

It produces, as writer and neuroscientist Erik Hoel says, semantic satiation. Only the first one ignites debate. Then the copycats kill the value of the original. If the merit of a piece on artistic grounds ends there, it just won't last. It happens with human art as well; that's why no one thinks of that urinal or the duct-taped banana except through their historical value as meta art.

So the question will morph again, one last time: will artists manage to use AI to create a new form of art? Something akin to photography or digital art. Neither by copying humans nor by opposing them. Art in its own right. No one called a photograph artistic unless it proved to be deserving of that merit. One example of how AI artists could embrace this approach is what designer and blogger Celine Nguyen calls “aleatory art”:

I’d like to propose that we think of generative AI as a technique for producing aleatory artworks. Much of the angst around AI, to me, comes from observing the stochastic, indeterminate, unpredictable nature of it—and framing these things as flaws. But in aleatory art, these qualities are useful and productive: They invite the artist to produce works through different processes, which lead to different aesthetic outcomes.

This is something only doable with AI because the idiosyncrasy of the technology—not knowing fully how it works, its biases, its statistical nature—is what gives birth to what we interpret as randomness of output. This is just one idea of many. I won’t try to predict all the things people will come up with.

The bottom line is that AI, like all other technological innovations before, has features that manifest the idea that the “medium is the message.” If there’s a sense in which AI masterpieces could exist, it won’t be by reinventing the brush. And, circling back to de Freitas’ question, the only reason there are none yet is that no one has dared go far enough.

I’ve read your essay and find myself agreeing with much of its anatomy of “neck vs necklace,” yet still questioning the conclusion you draw from it. You’re right that great art needs a thick, particular context, and your Guernica-in-the-woods thought-experiment makes the point vividly. But the essay treats generative systems as if they stand alone, when in fact every non-trivial AI artwork already arrives encased in multiple layers of human meaning: prompt, curation, framing, display, reception.

You also grant, late in the piece, that “someone will eventually create an AI masterpiece,” yet most of the argument reads as though this were impossible in principle. Photography offers a useful timeline check: in 1841, barely two years after Daguerre’s first public demonstration, it would have been premature to pronounce the absence of photographic masterpieces; Stieglitz’s The Steerage and Atget’s Paris were still half a century away. Declaring a deficit now, when generative tools have been publicly available for scarcely three years, risks repeating the same snap verdict critics made about early “mechanical” cameras.

Finally, the essay often equates “AI art” with raw, unedited machine output, then measures that output against canonical paintings. Yet the most serious practitioners work exactly where you say meaning is made: they choose or even shoot the training data, design prompts as scores, iterate, crop, print, mount, title and tell stories around the images. In other words, they restore the very specificity you claim is missing.

So I share your intuition that the first undisputed AI masterpiece will arise when an artist harnesses the medium’s native properties like stochasticity, scale, recursion rather than using it for mimicry. I just doubt we’ll recognise that moment if we decide in advance that no such work can yet exist. The history of new media suggests we’re still far too close to the invention to make that call.

A lot of what makes art art is intention, including expression of ideas and feeling. It’s makes the artist feel something, or the viewer feel something, or both.

A problem with AI generated outputs and their proliferation is the Bach faucet problem, which has been ongoing for sometime in generative imagery:

https://x.com/jasonbaldridge/status/1591783325303177217?s=46

The ghibli effect was the most recent instantiation of this.

Overall, I think a mistake many people make, both AI fans and AI skeptics/haters, is that the end state is that we can make the standard images, movies, music. Instead, we need to broaden the aperture to new forms of artistic expression, storytelling, etc, that taps into these tools to bring new visions and experiences to life. Think: truly generative stories and experiences, branching narratives, interactive mysteries, and who knows what else.