Why Ads on ChatGPT Are More Terrifying Than You Think

6 huge implications for the future

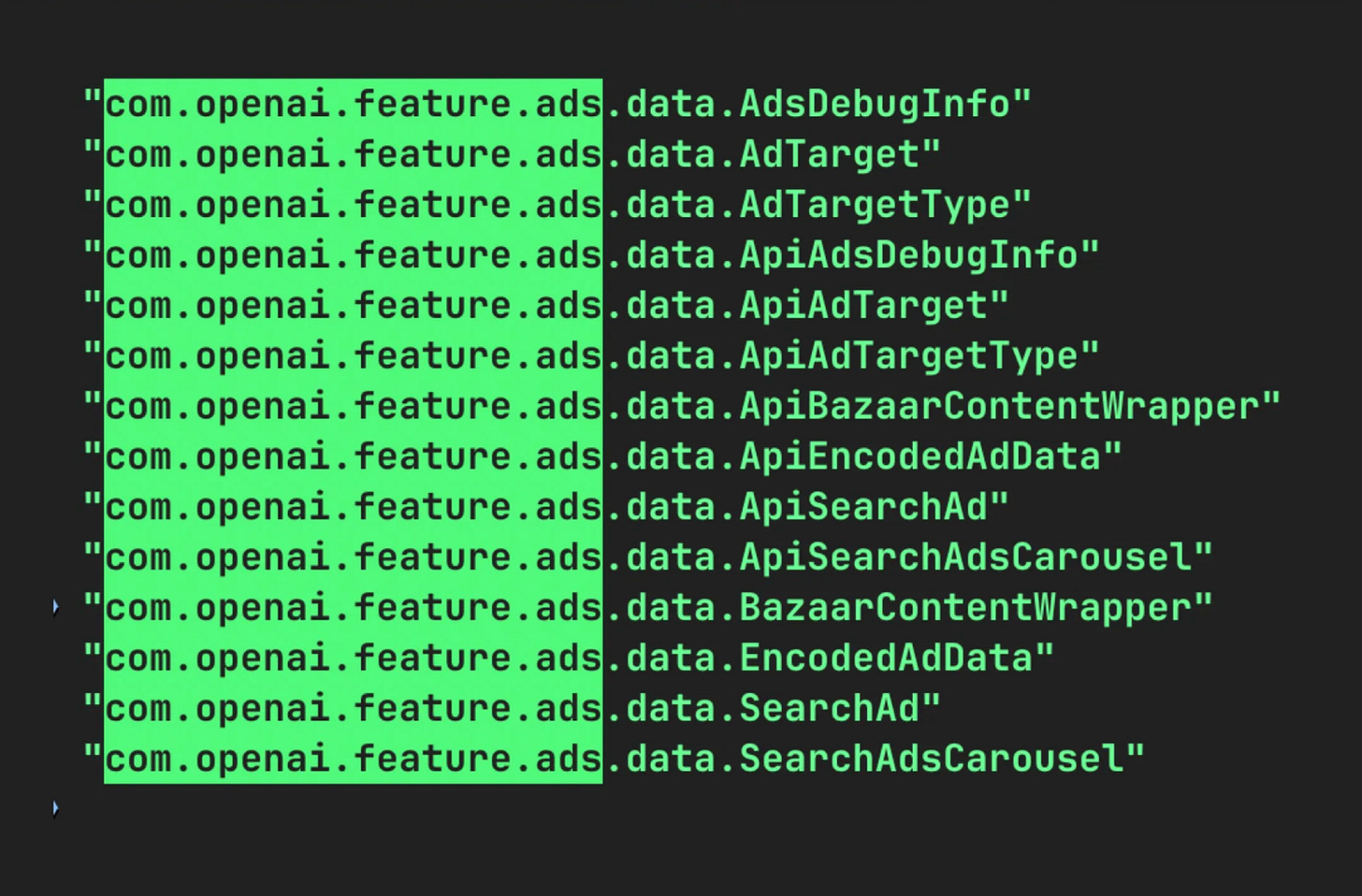

OpenAI’s silent confirmation that advertising is coming to ChatGPT (screenshot above) marks the end of the chatbot’s introductory phase and the beginning of a new nightmare for users. While the timing aligns with its third anniversary—happy birthday to you, I guess—framing this as a self-gift rather than a necessary structural pivot would be naive; OpenAI will sell ads, or it will die. (Last-minute news from The Information reveal that CEO Sam Altman is sufficiently worried about Google’s Gemini 3 that they’re considering delaying ads and similar initiatives in favor of improving the quality of the model.)

It is a bad sign that this is a forced move rather than a free choice, though: People would complain anyway if OpenAI wanted ad revenue to amass some profits, but that’s standard capitalism; the fact that OpenAI can’t afford the things it intends to build unless it enables ads suggests a fundamental flaw at the technological level: maybe large language models (LLMs) are not a good business (the financials don’t paint a pretty picture so far). If that’s the case, then this is not an OpenAI problem but an industry-wide catastrophe: whereas traditional search engines display ads because users want free information, chatbots will have ads because the costs are otherwise untenable.

The unit economics of LLMs have always been precarious; the cost of inference—the computing power required to generate a response, which is, accounting for everything, larger than the cost of training a new model when you serve 800 million people—remains high compared to web search because small-ish companies like OpenAI need to rent their compute to cloud companies like Microsoft; their operational expenses are sky-high! (cloud-high one might say). The twenty-dollar subscription tier (chatbot providers all have converged at ~$20/month) was an effective filter for power users, but it was never going to subsidize the massive operational costs of the free tier, which serves as both a user acquisition funnel and a data collection engine (and thus a fundamental piece of the puzzle, in case you wondered why OpenAI offers a free tier in the first place).

(Short note: the reason AI model inference is expensive for OpenAI compared to search for Google—say, a ChatGPT query vs a Google search query—is not that the former requires more energy than the latter; according to the most recent estimates they’re in the same ballpark! (Note that this doesn’t account for reasoning queries, which might generate 10x-100x tokens, raising the bill accordingly.) But even if we set aside the cost of reasoning traces, the reason serving AI models is expensive is that they require high-end GPUs that companies like OpenAI or Anthropic or similarly small ones need to rent to cloud platforms like AWS, Azure, GCP, or Oracle. Renting GPUs, turns out, is extremely costly.)

The transition from monthly subscription to advertising pushes OpenAI out of “research laboratory selling access to intelligence” territory into “full-blown media company selling access to attention” territory, just like YouTube or Facebook. Let me be clear about this: building AGI (general AI) to “benefit everybody” was always a cool genuine goal but ultimately a distraction; you can promise the heavens for free but only until you need to hit revenue targets to appease investors. OpenAI is not hitting them. When even the biggest companies in the world—actually, the biggest companies in history—are resorting to debt because they can no longer pay with cash the immense capital expenditures they’re incurring (they don’t rent GPUs like OpenAI, they build datacenters), you can be sure that smaller companies like OpenAI will have to get their hands dirty and take measures they’d rather not take, like ads, short video slop, and erotica. That's how OpenAI expects to be profitable by 2029 despite incurring immense costs now at a fairly low revenue.

Anyway, I see advertising as a tragic shift in the incentive structure of ChatGPT (generative AI in general, if others follow suit) because, all of a sudden, OpenAI’s primary client is no longer users but the advertiser (subscription revenue matters but a few billion dollars a year is nothing compared to what Google and Facebook make selling ads). We have seen this progression in search and social media (which appears to be a “business strategy”) but applying this model to generative AI introduces unique risks and complexities that we can’t yet understand.

The era of information retrieval (links) is giving way to an era that also includes information synthesis (AI outputs + links), which will eventually evolve (involve?) into an era of just synthesis (no links anymore). Once it happens, it will become immediately clear that monetizing synthesis carries problems that monetizing a list of links don’t. Here are six implications of this shift that will unfold in the coming years:

In-stream advertising

The death of the click

Visual product placement

Targeting your anxieties

From SEO to LMO

The AI-rich and the AI-poor

I. In-stream advertising

The core utility of an LLM is the ability to compress vast amounts of data into a single, coherent answer (that is, when it doesn’t hallucinate). We value this distillation because we assume it is derived from a “neutral” weighing of the available facts: ChatGPT goes on Google search and gives you a response from, presumably, a good mix of sources. Advertising introduces a perverse incentive that directly undermines this utility. Unlike a search engine, which presents paid options alongside organic results (already harming the user experience in what’s commonly known as “enshittification”), an LLM will integrate ads into the answer itself.

A study by Sharethrough/IPG Media Labs from 2015 (am eternity ago), conducted on 4,770 consumers using eye-tracking technology, showed that native advertising—ads that blend into content—are viewed 53% more frequently than traditional banners. The bottom line is obvious: the more “disguised” an ad, the more the consumer treats it as part of the information they expected to consume. Now, imagine what happens when the ads are intertwined with the AI output seamlessly—in-stream advertising—like part of the story:

With the global native advertising market projected to reach $400 billion by 2032, the financial pressure to exploit this in-stream inventory will be irresistible and the options are infinite. The number of “viewed ads” will essentially reach 100% (anyone will realize this is quite revolutionary for the advertising industry) because you don’t avoid something that you don’t know is there.

Are companies legally required to disclose the ads? Good luck proving the fact that the main character in your generated fanfiction novel drives a 2026 Ford is an ad. If the model is financially incentivized to favor whatever brand, that bias will be woven into the logic of its output, probably at the post-training level (that is, AI companies will reinforce behaviors into the model that align with the advertiser’s interests, for that is the safest, most reliable way to influence the AI’s behavior and they already do this for other reasons, like steering personality). No one except them has access to the post-training data and it’s not possible to do an “inspection” into the model: its black box nature prevents tracing the source.

And so the AI model will safely frame the “best” solution not as the most efficient one for the user (what you assume), but as the one that generates the highest yield for the advertiser on a cost-per-mille basis (what you get). I hate when Black Mirror nails the future so accurately that it feels like an example of the Torment Nexus. But, unfortunately, I don’t think it’s hyperbolic to claim that putting ads into ChatGPT is such an insidious move that we can call it a torment to the digital world.