How AI Will Reshape the World of Work

The manager's apprentice

I. The vanishing threshold

We are witnessing the burning of the bridge behind us. For a century or so, the corporate social contract has been built on an unspoken agreement: young people—interns and juniors—would accept low wages and tedious grunt work in exchange for proximity to expertise and the possibility of climbing the career ladder. In journalism, for instance, the usual tasks were fact-checking, tape-transcribing, meeting summarizing, and coffee fetching; although low-stakes and low-value, they allowed juniors to absorb the “culture” and rules of their profession, and most importantly, implied a sort of career pipeline for the future. A paid onboarding into the labor market.

I write in the past tense because AI has torched this contract: we can debate what the world will look like in 10 or 20 years—whether by then innovation has created more jobs than it has destroyed and so on—but what the world looks like today is pretty clear and pretty unpretty.

Let’s do a quick review. SignalFire, a San Francisco-based venture capital firm, found that fresh graduate hiring by big tech companies globally declined more than 50% over three years, with only 7% of new hires in 2024 being recent graduates. In the UK tech sector alone, graduate roles were slashed by nearly 46% between 2023 and 2024. Entry-level hiring at the 15 biggest tech firms fell 25% also in the 2023-2024 period. CNBC reports that postings for entry-level jobs in the U.S. overall have declined about 35% since January 2023, according to Revelio Labs, with AI playing a big role. A 2025 survey sponsored by Hult International Business School found that 37% of employers would rather have AI do the job than a new grad. In March 2025, the unemployment rate for recent college graduates (ages 22-27) was 5.8%, considerably higher than the nation’s 4% overall rate at the time, according to the New York Federal Reserve.

The Wall Street Journal identifies the core mechanism: “The traditional bottom rung of the career ladder is disappearing.” In the past, technology hit the manual laborers first, but AI “presents a different challenge than past technological disruptions—in large part because it is eliminating the entry-level positions that traditionally served as stepping stones to career advancement.” Derek Thompson, a former The Atlantic staff writer, interprets the data similarly:

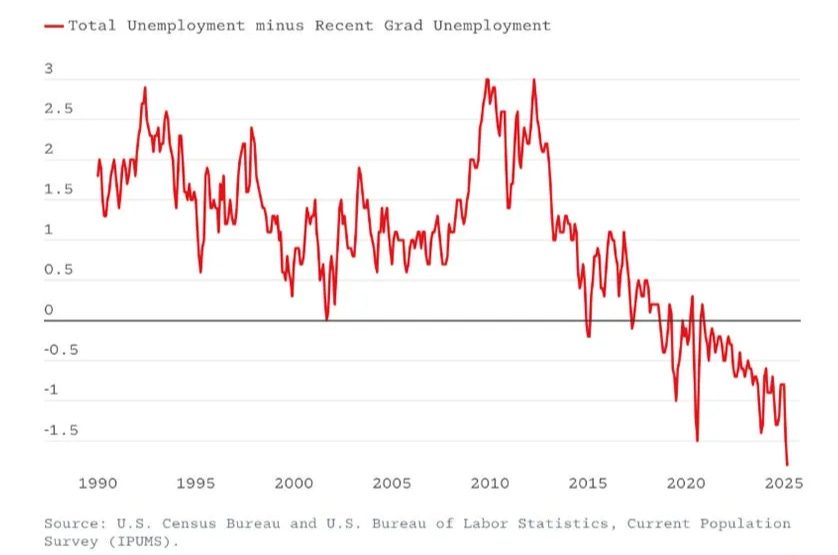

[The graph below] is exactly what one would expect to see if firms replaced young workers with machines. As law firms leaned on AI for more paralegal work, and consulting firms realized that five 22-year-olds with ChatGPT could do the work of 20 recent grads, and tech firms turned over their software programming to a handful of superstars working with AI co-pilots, the entry level of America’s white-collar economy would contract.

Corporate layoffs tell the same story.

Challenger, Gray & Christmas, the outplacement firm that tracks layoffs, recorded nearly 55,000 AI-linked job cuts in 2025 alone, a category that barely existed in their data two years ago. The scale is striking, but more so the candor: Amazon CEO Andy Jassy told Reuters that generative AI “should change the way our work is done. We will need fewer people doing some of the jobs that are being done today . . .” Of course, he’s not referring to seniors or executives like himself. IBM confirmed AI agents had already replaced hundreds of back-office roles. Chegg laid off 45% of its workforce as students turned to generative AI tools instead of traditional homework-help platforms. Microsoft cut 15,000 roles in 2025, which a company spokesperson described as “organizational changes necessary to best position the company for success in a dynamic marketplace.” (I bet writing that kind of corporate PR is part of AI’s job right now.) CEO Satya Nadella revealed that 30% of the company’s code is now AI-written while simultaneously laying off software engineers; Sundar Pichai says it’s 25% for Google. Anthropic CEO, Dario Amodei, predicted that, by March 2026, AI might be “writing essentially all of the code.” (That prediction might be far-fetched, but the intent is clear.)

I will admit that the layoff data is perhaps the data I trust less, for tech companies and executives have vested incentives to make up a story about how incredible AI is; the layoffs are real, as is partial AI replacement of boilerplate tasks, but the underlying motivations might be more prosaic. The pattern, however, is consistent across sectors beyond technology.

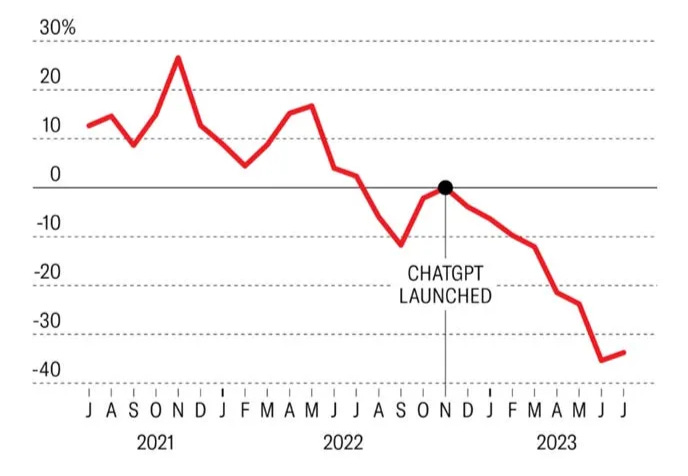

In creative fields, a study on Upwork and Fiverr found that writers, graphic designers, and translators saw job postings drop 21% for “automation-prone jobs” within eight months of ChatGPT’s release, with image-related work declining 17% after DALL-E and Midjourney launched in 2022 and writing-specific jobs plummeting by over 30%. Earnings followed the same pattern: writers lost 5.2% of their monthly income; image workers, 9.4%.

In the legal sector, Paul Weiss chair Brad Karp said “junior associates [will be] supplemented, if not significantly replaced, by technologists and data scientists for a broad portfolio of projects,” while a 2023 Goldman Sachs report estimated 44% of legal tasks could be automated by AI. Same thing in accounting. A professor told Fortune: “Accountants are not doing well . . . only the extremely senior people survive.” A Bloomberg analysis shows MBA placement at elite programs collapsing: at Harvard, 4% of graduates had no job offer three months post-graduation in 2021; by 2024, that figure hit 15%. As Fortune confirms: “MIT saw a similar change, with its share of offer-less graduates climbing from 4.1% to 14.9% in a matter of three years.”

More than a temporary trend, as some love to repeat, this is a structural breakage: the bargain was always exploitative, but at least it was available; now it’s neither fair nor there. I don’t think AI is the whole story—nothing is ever mono-causal—but it seems to be a large (and growing) factor, and workers, particularly new grads and would-be juniors, are raising their anxiety levels accordingly.

A Deutsche Bank survey conducted in the summer of 2025 (10,000 respondents) reveals that 24% of US and European adults aged 18-34 express high concern (8/10 or more) about losing their jobs to automation, compared to 10% adults aged 55 or above. A Pew Research Center survey conducted in October 2024 (5,273 respondents) finds similar levels of unease: “About half of workers (52%) say they’re worried about the future impact of AI use in the workplace, and 32% think it will lead to fewer job opportunities for them in the long run.” A survey by the Institute of Finance and Management (588 “accounts payable” professionals) found that 45% of AP professionals fear layoffs, up from 27% in 2024.

It’s no longer a debate whether worker disquiet is warranted. It is. But what are they replacing these juniors with in terms of output? Is the automation process cost-effective? Is it a reasonable long-term investment or is it a short-term gamble?

To respond to those questions at once, Harvard Business Review coined Workslop, which is “AI-generated work content that masquerades as competent output but is, in fact, cargo-cult documents that possess the formal qualities of substance yet entirely lack the conceptual scaffolding.” This might sound slightly dismissive (and in some cases it’s unfounded), but the bottom line is clear: AI can’t replace juniors even if companies remain convinced that it can.

Executives believe they are swapping a $40,000 junior for a $20/month subscription, but they are actually inviting what, in The Naivete of AI-Driven Productivity, I described as an “inflationary spiral of inefficiency.” Instead of training a human mind, senior staff now face a “cascading series of time-sinks . . . and the final, tragicomic time wasted in simply redoing the work from scratch.”

Here’s my take: Firing juniors (or not hiring them in the first place) will cut financial costs at first, but it enables a long-term hidden cost, a kind of tacit debt that replaces the learning curve with a curve of shortsightedness, waste, and eventual demise. This is a suicide model. When you replace kids who would eventually learn the know-how of any role with AI models that lack continual learning, embodiment, or a way to internalize those things you can’t read in a book, you’re signing your own death sentence. That’s a strong assertion, however, so let me make my case first before telling you the solution. You have the data, now hear the story.

II. The tacit dimension: what AI cannot replace

To understand why AI is not the solution we’ve been promised, we must confront a paradox that confuses even the experts: they have built models with god-like explicit knowledge (they can solve mathematics and coding challenges that surpass 99.9999% of the human population), yet the office remains stubbornly human. As podcaster Dwarkesh Patel recently noted,

If you showed me Gemini 3 in 2020, I would have been certain that it could automate half of knowledge work. We keep solving what we thought were the sufficient bottlenecks to AGI (general understanding, few shot learning, reasoning), and yet we still don’t have AGI (defined as, say, being able to completely automate 95% of knowledge work jobs).

He says the reason is that our definitions of AGI are “too narrow.” I say that the reason is that human work is far more complex than we’d like to admit. Our subsequent definitions of AGI will still fail because most tasks—especially those we take for granted—are solved with tacit knowledge.

In the 1950s, polymath Michael Polanyi introduced the concept with this maxim: “We know more than we can tell” (Polanyi’s paradox). Some information can be codified or expressed—that’s explicit information—but the tacit know-how is embodied, intuitive, and learned only through experience. Whereas AI is the emperor of explicit knowledge, it fails at tasks that require know-how because it lacks the friction of reality; you only learn this by interacting with the problem in the real world.

Consider this anomaly in the latest Hunger Games novel, likely an artifact of AI assistance, which I’ve cited before as a clear case of “explicit-tacit confusion” in AI-generated writing: the text describes a character rubbing a spiderweb between her fingers, calling it “Soft as silk, like my grandmother’s skin,” but this ignores the primary tactile reality of a spiderweb: its stickiness. The AI links “spiderweb” to “silk” to “soft” because it lives in a statistical labyrinth. But the problem goes deeper than sticky webs mistaken for silk robes. AI hasn’t replaced us because, in my own words, “the majority of human work is not the crisp, measurable deliverable but the intangible, fuzzy, and utterly essential labor of context-switching, nuance-navigation, ambiguity-management, and task-coordination.”

When they fire/not hire juniors and force seniors to manage AI, they fall into the “coordinator’s trap.” AI might take over tasks rather than entire jobs, but that’s hardly reassuring when this is a faithful portrayal of the state of labor: “By splitting work into fragments, AI forces us into the role of coordinators . . . it’s a kind of labor more exhausting and delicate . . . than the job we had before.” We are left with a system where “throughput is defined not by its strongest link but by its weakest.” We have the AI (blissfully ignorant of context) and the human (distractible, bored, and now exhausted by supervision). As I wrote back then, and I still believe: “Workslop” exists not so much because AI is incompetent as because humans are still human. This brings me to a critical realization that I shared in As AI Gets Better I’m Less Worried About Losing My Job:

It is so easy to romanticize the idea of trades and craftsmanship [yet] trades are not only often a sounder financial path than endless study, but may also unlock . . . a long-forgotten form of prestige. . . . It’s time for young people to take advantage of the circumstances; to reconsider the value, personal and societal, of pursuing a trade: there are way too many college graduates . . . and AI is a greater threat to office jobs, including my own, than any know-how-heavy manual trade.

I think I went over the top: pursuing a trade is great, but it can’t be extended to become a systemic solution; many people have office-targeted knowledge acquired over many years, and among them, most will want to pursue that career path rather than re-imagine themselves entirely. I’ve found a better solution: The solution is for the analyst’s job to start looking like the welder’s job. Companies should not replace everything with AI, but they shouldn’t reject technology either: they should rediscover the value of apprenticeship. AI will enable a hybrid mix of trade-like, guild-like tacit passing of know-how knowledge, combined with the comfort and reliability of office work.

Corporate jobs will become more and more like trades, either by choice or by imposition. The explicit part of the office job is now essentially free—tell me, how many medieval blacksmiths in the entire Middle Ages read a manual before starting to hit on the anvil with the hammer?—or should be taken as such by those enterprises that want to stay in business, presumably all of them. The tacit part—the craftsmanship of navigating ambiguity, the anvil-hammering—is what’s left.

Most enterprises won’t embrace apprenticeship-based dynamics that are traditionally typical of trade work; it’s hard to shift logistically and attitude-wise. But the alternative is obsolescence.

What I’m saying is not that every sector will become a guild but that those that fail to resemble one to the extent that AI requires them to do so will die. I’m talking about a survival mechanism, about the next stage in the evolution of capitalism: the survival of the fittest, and the fittest will be those who embrace AI but also learn to navigate around its failure modes.

III. A case study in AI-enhanced guild-like journalism

Journalism is the canary in the coal mine. It is an industry obsessed with facts (explicit) but defined by judgment (tacit). If you let AI write your news articles (as some outlets have unsuccessfully tried), you will end up with workslop that needs to be thoroughly fact-checked and audited by seniors. There are ways to introduce AI into the work of a writer, but you need to first know what you’re doing. For instance, will AI ever acquire taste, a fundamental skill to know which stories to cover, what angle to pursue, how to address the interviewees, etc.? I say, not in the short term. Taste is a crucial skill for the journalist, and yet it’s only acquired by developing a sort of intuition or instinct that’s beyond reach for AI models.

So, let me construct a viable model for a “new guild” newsroom that integrates AI without discarding the human future. Instead of replacing the juniors to augment the seniors, why not let AI augment both in the explicit dimension and allow workers to return to a tacit apprentice-master relationship? I have described qualitatively what that looks like in this section. In the next one, I have ventured a quantitative version, more speculative but also more tangible. Here’s what the current standard model vs. the “suicide model” vs. the “new guild” looks like for a journalist:

The old model (pre-ChatGPT): You hire 6 juniors. They spend 8 hours a day transcribing interviews, aggregating press releases, and writing police blotter briefs. They are exhausted, paid poorly, but they learn. Eventually. (Most of them will never go further than places like Futurism.)

The suicide model (current trend): You fire/not hire 6 juniors. You buy an enterprise AI license ($200/month, a bargain). The AI aggregates the press releases and writes the briefs and so on. The senior editors fact-check the AI or, in the worst cases, rewrite the thing entirely from scratch because AI’s tasteless choices are unpublishable. Costs drop immediately because you don’t have to pay any slow-learning juniors. In 10-15 years, the seniors start to retire, and the publication dies because AI has not managed to develop any taste in the meantime.

The new guild (apprenticeship): You hire 3 apprentices. You keep the AI. The AI aggregates the press releases and writes the briefs, doing most of the grunt work. On the other hand, the apprentices work with the seniors hand-in-hand, just like an electrician or a plumber would. They learn to hand over the explicit work for the AI and internalize the tacit knowledge by seeing how a senior journalist does things. Over time, they become seniors who know standard journalistic practice and know how to use AI.

Here’s how the workflow shifts to prioritize tacit learning while using AI for the grunt work. (Keep in mind this is a toy example; it’s the company’s responsibility to figure out how to adapt the existing workflows to the new tools and how to adopt this apprenticeship-based organization to reduce costs while dodging the disaster they’d incur if they don’t.)

09:00 AM. Task: A 50-page municipal budget report is released. In the old way, the junior would spend 6 hours reading and highlighting it. In the new way, the apprentice feeds the PDF into the AI. Example prompt: “Summarize key variances in public safety spending.” The apprentice is not “doing” the summary but auditing the AI. They are learning to spot what the AI missed. This turns a 6-hour task into a 30-minute or 1-hour task.

10:00 AM. Task: The senior editor is interviewing a hostile source, a politician accused of corruption. The apprentice sits in and does not speak; he observes the senior’s body language, watches how the senior uses silence to force the politician to keep talking, and sees the senior abandon the prepared questions when the source slips up. In the meantime, the AI records and transcribes the interview. The apprentice is focused entirely on the human dynamics.

02:00 PM. Task: Writing the story. The apprentice drafts the story using the AI-generated budget summary and the AI-generated transcript. They focus their energy on the lede (the opening hook) and the nut graf (the context). The senior editor sits with the apprentice. They fix tone and rhythm and ensure editorial standards (AI nails the grammar). Senior: “See how the AI phrased this accusation? It sounds litigious. Soften it to ‘alleged’ but keep the punch. Watch how I rewrite this sentence.” Over time, the apprentice learns judgment and taste.

This is, of course, a simplification of the current role of junior/senior journalists as well as how AI could be integrated into existing workflows, but it works as a quick illustration. As I wrote in Why Obsessing Over AI Today Blinds Us to the Bigger Picture, it’s impossible to predict how technology will change our ways of doing things. It’s an iterative, discovery-based process that takes a lot of time to standardize into manuals, habits, and customs.

You can support my work by sharing or subscribing here

IV. Calculating the ROI of apprenticeship

The moral and socio-political argument is strong—poor juniors, we’re leaving them a broken world—as is the qualitative framework, but the financial argument must be bulletproof: does this reduce costs? When? How? Executives are addicted to the immediate savings of firing juniors (certain cost reduction now < potential cost reduction in the future). We must show them the cost of Ignorance—the tacit debt—using a rigorous financial model that compares a no-junior AI-only “suicide model” to the “new guild” of AI-enhanced apprenticeship.

Baseline assumptions:

Senior journalists cost $117k/year (includes benefits, overhead).

Junior journalists cost $52k/year (salary only, minimal overhead).

Seniors stay 6 years on average; replacement costs 150% of salary.

AI subscription runs $200/month per user (e.g., ChatGPT Pro).

Baseline scenario (status quo): A mid-sized team with 6 seniors and 6 juniors. Annual cost: $1,014k ($702k for seniors at $117k each, $312k for juniors at $52k each). The juniors handle grunt work—transcription, research, document prep—freeing seniors for high-value tasks. Knowledge transfer happens informally. When seniors leave, juniors step up. The system works, but it’s expensive; AI offers a seemingly obvious cost-cutting opportunity.

Both scenarios below—A, the suicide model, and B, the new guild—eliminate this baseline structure, replacing it with different configurations that trade immediate savings against long-term capability. I explore how both of them compare to the baseline and to one another. (I use informed and realistic but ultimately made-up numbers. This section took me a lot of time to write, and I think it best presents the case to those who will make the decisions, whereas the rest is more informative for a general audience.)

IV.1 Scenario A: suicide model (all-in bet on AI)

Fire 6 juniors, give AI tools to existing seniors.

Year-1 savings: $312k minus $14.4k in AI subscriptions (6 seniors × $200/month). Net savings: $297.6k. This is why CFOs do it. But three costs that compound over time aren’t visible: