It’s an easy trope to say the internet is dead or dying. That it’s mostly garbage in the form of cheap entertainment or that life is better in the real world so we should all go out a little more. The truth is that online land is too complex, heterogeneous, and layered for any of those descriptors—those that reflect its deplorable state and those that emphasize how any alternative is preferable—to make it justice.

Facebook is dead, but that doesn’t mean Substack is. TikTok is mostly brain worms but some accounts are funny. Sometimes. Authors of the best books in your local store often write online blogs, hosted in some WordPress you can easily google. And, unless you’re all bots (which you can prove, to give you an idea, by liking this article), the internet is very much alive to me.

So if we’re going to argue there’s an impasse and the incoming massive logging-offs are real this time (as I will do here) we need an equally multifaceted set of reasons that could explain such shocking collective behavior. Leaving our terminally online lives behind requires strong justification.

It’s always risky to give it another shot at a topic that’s been touched upon to the point that the very sight of the headline makes our eyes roll up. I can fail terribly and end up adding to the pile of internet garbage about how the internet is garbage (making the article, in a way, more true in the process).

But I may succeed at convincing you that there’s something novel and special going on: Three ingredients—all big enough for themselves to scratch the status quo but none, alone, capable of changing it—are converging at this singular time.

The great digital exodus is cooking in the cauldrons of history and this is the recipe.

The first ingredient is the lack of available jobs that happen on a computer

Whatever it is that studies say now—I’ve read all kinds of predictions and analyses and mixed reviews (some of them backing up this observation)—one thing is universally acknowledged: AI will take many people’s jobs.

The analysis is rightfully mixed because AI will also create new jobs (as previous innovation waves have). The issue emerges when we realize that the people who lose their jobs (or stop having access to new opportunities) aren’t always the best prepared to take on the novel roles (or is a carriage rider automatically a good fit to fix cars?).

The factors at play are multiple.

There’s timing: A job requires a background of many years of preparation. How can students predict what’s changing in eight years (the approximate duration of senior education) so that they can benefit from fast technological change?

There’s location: Are poor people in poor countries the ones that OpenAI, Google, and Meta will hire to maintain their robot fleets for a high salary or will they become, perhaps, part of the “tasker underclass” of thankless laborers who quietly keep afloat the companies?

There’s flexibility: Go tell a 45-year-old office clerk that ChatGPT will take over and she needs to learn nursery or advanced software engineering, or perhaps farming or steel bending. (It’s arguable that people should keep a minimum level of awareness and ability to adapt to changes, but that works as an individual solution to a social problem).

The people who happen to be unlucky in timing, location, and flexibility—which is, by the rule of the power laws that govern these things, the vast majority—won’t survive thanks to AI, but despite it.

The mixed analysis also responds to an optimism-inducing fact that doesn’t sell well on press headlines: AI doesn’t take over jobs but tasks. I like this catchy maxim by economics blogger Noah Smith: “Dystopia is when robots take half your jobs. Utopia is when robots take half your job.” I’d be compelled to agree with his appealing conclusion if I agreed with his premises. Don’t get me wrong, enhancing people instead of replacing them (not what everyone is doing) is great.

But we live under a socioeconomic system where profits rule and supply value depends on a ceiling set by demand, which means that my enhancement can be your replacement.

Smith (Noah, not Adam) says our comparative advantage as humans is the way out of this mess. Even if AI systems could do our work—both standalone tasks and entire jobs—better than we ever could (to picture that, take DeepMind AlphaZero and extrapolate it to everything else), it wouldn’t affect us too much as long as computing power, a resource specific to AI systems, is finite. That’s the counterintuitive property of comparative advantage (not to be confused with competitive advantage): We can always do what we’re best at, even if there’s some AI system that could, in theory, do it better. For instance, facing a GPU shortage, tech companies would allocate AI productivity increases to coding but not to writing novels. We’d write the novels.

But even Smith is not so sure anymore. Humans and AI systems both depend on a resource more basic than computing power: energy. What if a company like Microsoft decided, I don’t know, that taking water from the Arizona desert to cool down data centers was better than letting some poor farmers quench their thirst and irrigate their fallow fields? Or if OpenAI thought that using an amount of electricity that could power 50,000 homes for ChatGPT to fail at commonsense reasoning tasks regardless of how many versions they release, was an affordable opportunity cost?

If companies decide that energy is better allocated to building AI systems even when their utility is still rather limited, we’ll carry a heavy burden. No comparative advantage could save us from that fateful tragedy.

But let’s not be unfair. Software and hardware get more efficient over time (how else did OpenAI manage to make GPT-4o twice as fast and twice as cheap). Likewise, energy supply, like wealth, grows over time, and as it grows it cheapens. That’s good. Is AI helping it grow, though? Does it grow fast enough? Is energy distributed fairly? Let me answer with another question: When is anything in this world not distributed fairly, right? Let’s accept, as Steven Pinker says, that inequality is an inevitable feature of technological progress. That’s fine because the tide rises for all—in the long run.

But in the long run, we’ll only see what AI made possible, not what it made obsolete. Except for those left behind, who will remember the ships the tide sank.

The hard truth is, however mixed our current analyses appear to be, that, directly or not, sooner or later, many digital workers—creative or otherwise—will be forced to make a profound career change because of AI. Be it because they lost their jobs to AI right away, or their employer wants to cut expenses and a smaller AI-human tandem team is enough, or the newly created jobs don’t fit their skill set, or their comparative advantage couldn’t save them, or, funnily enough, their boss made the wrong decision moved by empty promises and overhype.

No one working on a computer (or whose main revenue streams require the internet) is fully safe. Writers, like me, are of course a target. ChatGPT is already taking the jobs of freelancers who now have to “walk dogs and fix air conditioners.” Staff writers aren’t in a better situation as newsrooms shrink for factors that inevitably include generative AI tools. Translators have been under attack since Google Translate became “good enough” and now are one of the most vulnerable groups.

This dark prospect also applies to artists and designers, developers and software engineers, teachers, human resources workers and other back-office staff, lawyers, bankers, social media influencers, porn stars… If I were to enumerate the entire list of affected careers that depend directly or indirectly on creating information, knowledge, art, and entertainment on or through the web, I might lose my job before I’m done.

The white-collar half of the world—those who at first dismissed (or at least relegated to a secondary issue) the threat of automation because they weren’t targets—are all marked now. Blue-collar workers (dedicated to manual labor) aren’t free of danger, but if AI automation feels like an extremely urgent problem today, it’s primarily because those who write job loss stories—like this one—are the ones losing their jobs.

AI’s disruption of internet-based jobs is doubly tragic. When companies realized the World Wide Web was where we’d spend most of our working time, people were forced to log in as their jobs digitalized. It was a mere proceeding for some. For millennials like myself—the OG digital natives—it was a blessing (or I wouldn’t be writing this). Yet for others, it meant saying goodbye to a lifetime of work. Who were the targets then? The very same people who now, due to AI, are logging off to walk dogs and fix air conditioners.

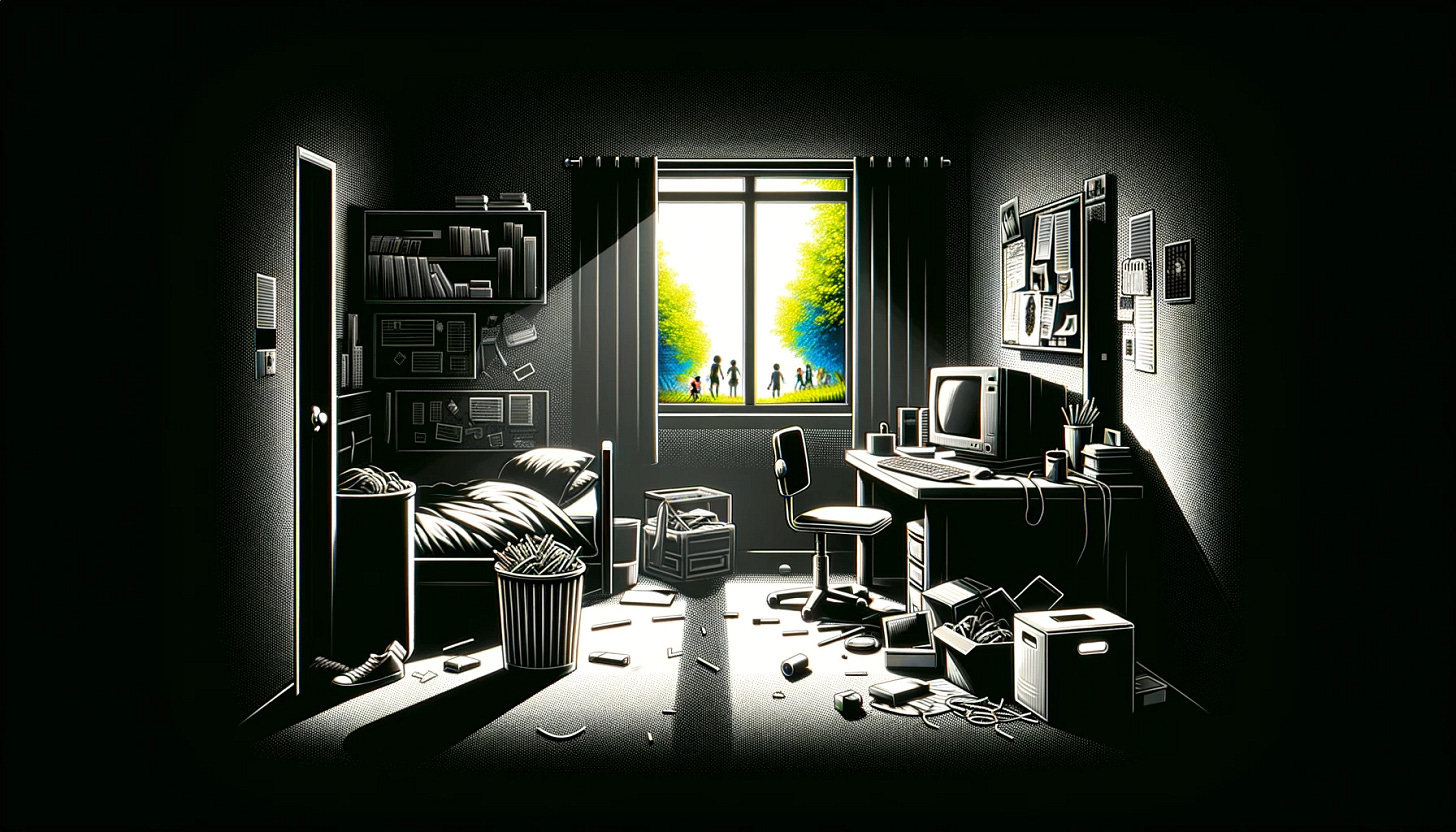

We’ll have to go back to the physical world—which, believe it or not, is still out there—to find a new life.

In a sort of reverse rural exodus (people left villages in the countryside to join the masses in bigger industrialized cities to find better financial opportunities), now netizens, who although distributed geographically all belong to the virtual land of silicon, will have to go touch some grass in an unprecedented digital exodus.

The internet dragged us in thirty years ago and now that we’ve grown comfortable living inside this unnatural environment, it’s kicking us out.

The second ingredient is the quality degradation of the online information ecosystem

I can say without a doubt that the internet is the tool that has provided me with the highest ROI in my life. There’s a variety of reasons for that. One is that I can find almost anything I want that I couldn’t otherwise—books, movies, music, but also people, news, and entertainment. I studied AI thanks to online courses. I met the most interesting and insightful people I know thanks to blogs and social media. I’m a writer thanks to writing platforms that didn’t exist 10 years ago.

Except for the people, who hopefully still have a physical presence, all the other stuff I get from the internet lives in the form of stored and processed bits and bytes of data. Information that’s transformed into knowledge or leisure. That information is precious, but it’s only as valuable as its source. If the source is low-quality or if it’s unknown, the info becomes unreliable and not worth my investment. Both, the provenance and quality of data and information on the internet are now under attack.

What happens when you no longer know where the information you consume comes from? When you can’t trust your eyes anymore? When text, images, voice, and even video are generated under your awareness? When some breaking news about the president or some controversy of the hottest celebrity happens to be a deepfake?

But wait, I’m overreacting. There’s evidence that the “epistemic apocalypse” we’re terrified of may not be such. We’re not so easily deceived, says historian Daniel Immerwahr. Deepfakes “are not reality-bending in the way most people believe,” as I wrote in a piece about OpenAI’s Sora. Immerwahr adds that we could even “take comfort from the long history of photographic manipulation, in an ‘It was ever thus’ way.” Are we overreacting?

Kevin Kelly asks why we expect to retain a “trust first, check later” mechanism forever when we’ve lived most of our history as a species with the exact opposite: “check first and trust later”? As I wrote for that Sora essay: “Generative AI is merely returning trust to its rightful place, conditioned in our individual ability to ascribe it correctly.” A past history of successfully neutralized assaults on the information ecosystem—like knowing that photographic manipulation was always a common practice—is no reason to get our guard down.

So it’s not an overreaction or even panic—I’m just angry and sad: We had a superpower of trust we loved and relied upon (that we took for granted) and we’re giving it up. Should we be content for the time we had it because it was always going away? That’s dumb. Just as dumb as we are for allowing this to happen. Why can’t we have nice things?

We had a mostly unspoiled internet, with mostly reliable sources of our mostly healthy info diets, but we broke the chain of provenance. It’s gone.

In case that wasn’t enough, it’s becoming apparent that generative AI is being used, first and foremost, as a Bullshit-as-a-Service technology; a machine of low-quality content; a deadly pollutant. Why? Because it incentivizes aggressive capitalistic practices that damage the commons but benefit the infractors—for a short time. It’s the engine of a race to the bottom—someone does a bad thing first to win something, then everyone’s doing it to not be left behind and soon we’re all in the same relative situation as when the first infractor started but much worse in absolute terms because “the sacrificed value is gone forever.”

These dynamics can only be contained with coordination efforts we don’t seem capable of enforcing—or willing to—fast enough in the age of AI.

Let’s say one guy decides to use a GPT-like tool to conduct an SEO heist and steal the traffic of his competitor—which is something only a terrible person moved by the wrong incentives would do—in turn dumping into the internet a ton of AI-generated garbage. Now multiply this by all the terrible people (i.e. unscrupulous) with the wrong incentives (i.e. seeking money at all costs). Now scale it to 100x (because 1,800 articles, like that guy did, are rookie numbers) and the problem has suddenly swallowed the internet.

It’s terrible that we had, for a brief moment of a couple of decades, an epistemically robust, deservedly trustworthy, global, and decentralized information ecosystem that was for the most part high quality and we have to see it get destroyed by a few dumbass users who want to make a buck quicker than the rest.

But let’s be real for a moment. Is it so bad? Not that many people evaluate the trustworthiness of their sources, assess the provenance of the information they consume, or are worried about the trust flip that Kelly embraces as an ironic twist of destiny.

Most people open their platform of choice and engulf as much as they can—news, entertainment, gossip, even the new practice of “quick learning”—while scrolling as fast as they can. Well, that was always a dubious habit but it’s an actively harmful vice now that malicious generative AI users can create low-quality information and pass it as high-quality using the platforms we thought we could trust—they’re sending tainted messages that leave intact the medium to the detriment of the most naive and receivable—our young and old.

It’s much worse when the most powerful tech companies integrate half-baked tech at scale in their suites of ubiquitously used products for fear of losing yet another race to the bottom. Here’s what Wired’s Lauren Goode says about Google’s revamping of search with AI Overviews in an article appropriately entitled It’s the End of Google Search As We Know It:

Google's search overhaul comes at a time when critics are becoming increasingly vocal about what feels to some like a degraded search experience, and for the first time in a long time, the company is feeling the heat of competition, from the massive mashup between Microsoft and OpenAI. Smaller startups like Perplexity, You.com, and Brave have also been riding the generative AI wave and getting attention, if not significant mindshare yet, for the way they’ve rejiggered the whole concept of search.

If that doesn’t sound like a race to the bottom, I don’t know what does. And it’s not like Google has seen good results with previous versions of this new generative AI-enhanced search feature. When a consumer service used by more than two billion people worldwide doesn’t know that Kenya starts with “K,” we’re on the edge of a kataklysm.

It’s not just search. Perhaps a parent wouldn’t trust a random TikTok of Kim and Kanye teaching math or a suspicious YouTube science channel but what about their kids? What about the youngest of all, now exposed to disinformation in the form of YouTube videos for toddlers designed to attract them but intended to make money fast without any consideration for quality? AI tutors are coming but aren’t we rushing them a bit? I, a rather tech-savvy person, wouldn’t buy a book from Amazon from a random author or a random book from an author I know, but what about old people who log in on Google to search for “Google”?

Learning to use the internet was the highest ROI of my life but today, the ROI of spending one hour on the internet has been lowered to the point that it’s almost better doing anything else offline.

The AI flood might not drown us completely—at least not those who know how to surf the web—but it’ll spoil everything by soaking it in bullshit, which includes the vast majority of surface sites and big platforms most people frequent, where info is passively fed via recommendation algorithms. The eventual result of distrust, unsearchable provenance, and low quality is an unusable internet. One we don’t want to be part of.

One we don’t even know if we’re being part of.

This has taken different names that refer to slightly different forms of uselessness. I like the Dead Internet Theory and the Boring Apocalypse.

The DIT says the internet is mainly bots. You are mostly alone, like an island in an unfathomable ocean of meaninglessness. Everyone else you think to be real people are just bots. It was one of those conspiracy theories you laugh about because you’re sure it’s intended as a dark joke, then you see this:

Bots making AI pictures that deceive swarms of boomers on Facebook—except those swarms of boomers commenting with single-word compliments are also bots. This is the norm now (sometimes it’s not bots commenting, which is even sadder).

The Boring Apocalypse is the same thing except the focus is on the Ballardian picture of empty production and consumption. Imagine an engineer and his manager, who work for Ianepo. They communicate weekly over mail for an important project, an innovative AI tool that promises to increase productivity 10x. The engineer writes daily reports that he sends over to his manager religiously before every meeting, who, carefully goes through the emails to make suggestions. Except the engineer quietly and cleverly uses the tool, still a prototype, to transform his bullet points into entire documents and his manager, in turn, uses it to summarize them back into bullet points.

Jokes on you because their productivity increase is, as they claim, 10x.

You might think: Nothing of this matters because people who don’t realize they’re witnessing a chatbot zoo, who don’t care about sources, and who are more than willing to consume garbage all day, won’t leave in the first place. Even if they’re forced out by the waning job prospects, they will come back for entertainment and distraction—and to avoid boredom at all costs.

That’s why we need a third ingredient.

That’s why we need a good reason to leave.

The third ingredient is the social awareness that our mental health is in jeopardy

I remember conversations with my friends and my family about this around 2015. I used to say: “We will understand just how much damage the internet and especially social media has done to our brains when our young—social media native teenagers—grow to become adults and have to face the hardships of the real world.”

It’s happening.

We always knew that the internet, particularly smartphones and social media platforms, was addictive, not as an unavoidable feature of its nature but by design: Our inability to take our eyes off the screen or keep the phone out of sight, the dopamine hits from likes and comments, the endless scrolling tied to intermittent random rewards, and, well, the explicit admission from the pioneers that the earliest work in the social media space was built with a specific goal in mind: “How do we consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible?”—all of that are design decisions made by people who didn’t care about our mental health or cognitive development as long as we stayed online.

Now, it isn’t fair to say big social media and smartphones are all there is to the internet (or even that anything you can do with those things is bad for you). But most people use it that way because it is easier, because it’s what everyone else does, and because it works; it’s truly addictive. Not every addiction is equally harmful to you (you can consume heroine which destroys your body or read a lot of books which, well, doesn’t) but, as it happens, scientists have discovered that internet-related addictions are behind some of the most harmful, most pervasive effects to our mental health in the last decade.

We were always intuitively aware that the internet could be problematic. Now they’ve gathered the data and the prospect is dark.

Perhaps the highest profile scientist working on this is Jonathan Haidt, who also writes on Substack. Two of his most popular posts are Social Media is a Major Cause of the Mental Illness Epidemic in Teen Girls. Here’s the Evidence and Kids Who Get Smartphones Earlier Become Adults With Worse Mental Health. In March, he published an essay on the same topic in The Atlantic, entitled End the Phone-Based Childhood Now, and launched a book, The Anxious Generation, that covers all this in depth.

That’s just a tiny snapshot of his latest work on the relationship between phones, social media, the “great rewiring of childhood,” as he calls it, and the mental illness epidemic. I think you see the pattern. Here’s one excerpt from his The Atlantic piece, just to choose from the latest I’ve read from him:

I think the answer [to: “What happened in the early 2010s that altered adolescent development and worsened mental health?”] can be stated simply, although the underlying psychology is complex: Those were the years when adolescents in rich countries traded in their flip phones for smartphones and moved much more of their social lives online—particularly onto social-media platforms designed for virality and addiction. Once young people began carrying the entire internet in their pockets, available to them day and night, it altered their daily experiences and developmental pathways across the board. Friendship, dating, sexuality, exercise, sleep, academics, politics, family dynamics, identity—all were affected. Life changed rapidly for younger children, too, as they began to get access to their parents’ smartphones and, later, got their own iPads, laptops, and even smartphones during elementary school.

If there were doubts about the causal link between this pervasive and pernicious manifestation of online life, they’re crumbling down under the weight of vast amounts of evidence. I guess my hunch—as that of many others who saw this coming—was right: Social media and smartphone natives are becoming adults in shape and size, but are having a very hard time doing so in self and substance.

The anxious generation, as Haidt appropriately calls them, doesn’t want to be here. Teenagers no longer want to be on TikTok and Instagram. As Haidt writes about this study, “they would prefer that TikTok and Instagram were never invented.” They report both a profound aliment and a comparable impotence to get away from it. They scream inside as a result of this mind poison but they don’t get out—only tears filled with impotence, anger, and anxiety do.

Given the rising numbers of social media platforms and the absolute success of TikTok and Instagram among the youngest, I thought this had no solution, but Haidt’s work could help turn the tide. He and his team have set an ambitious goal that seems now more possible than ever before:

“By the end of 2025, we will roll back the phone-based childhood.”

That’s what makes this—the addiction and the anxiety—which has been historically perceived as the very reason why people stay logged in on social media when they don’t want to, the third ingredient of this recipe. Because the one thing that can destroy collective addiction and revert anxiety, depression, and suicide rates back to normal, is the kind of collective awareness and collective decision-making (which are possible now for the first time in a decade) that could push us to do something about this together, everywhere all at once.

It’s what could make us log off the internet.

If I were to ask my old teenage self—who had Facebook, Instagram, and an already dead Spanish social platform called “Tuenti”—why I remained online when I was feeling bad inside for doing so, my response couldn’t have been simpler: because my friends do. That’s the force that retains teenagers inside these deadly traps, that a significant part of their social lives happens online. You can’t cut ties with Instagram—even if it’s no longer a place to connect with your friends, as it was marketed in the beginning—without incurring an unaffordable social cost to yourself.

Back in 2015, if everyone in my circle had decided to delete Instagram when I did, I’d have been much happier.

Decisions of the kind “I’m getting off this poison for my own good at the expense of not spending as much time with my friends and, as a result, degrading my social connections possibly to the point of disappearance” are rare. Because they’re dumb. At least at that age, and because, until now, they were based on intuition. We have powerful evidence now at our disposal. Teens will still do what the group does (“find new friends” is terrible advice). Peer pressure is the strongest force at that age and if the dilemma is in choosing between relationships or sanity, we surely can say goodbye to our brains for a while.

This is what Haidt wants to change and the most powerful effect of his work: That dilemma, the entire conversation that surrounds it, is no longer internal—a silent monologue of guilt, shame, and anxiety. It’s a collective debate about the emotional and mental consequences that being terminally online inflicts on teenagers and about what carefully defined set of policies, norms, and actions we can collectively take and implement to reverse this grave mistake we made a decade ago.

If the group of friends you don’t want to lose by logging off is also aware of that debate, then you’re no longer a pariah for taking it seriously. You may, in fact, become a leader; a pioneer of a better life that others are, suddenly, ready to pursue instead of making fun of and ostracizing you.

This could create a top-down snowball effect; a positive social force exerting its blessing onto the individuals that would feel otherwise helpless to take action in the direction they already know is the better one.

How the three-part recipe comes together

Let’s put it all together in reverse order.

First, we’re now collectively aware that our mental health is terrible due to smartphones and social media and given the wealth of evidence of the negative effects of social media we agree we should do something about it.

Second, generative AI is degrading the provenance and quality of online data and information to the point that the ROI of being online isn’t worth it anymore.

Third, AI systems will cause a generalized reshaping of the computer-based job ecosystem with a growing lack of options and an anxiety-inducing uncertainty about employability.

What emerges from these three ingredients is a unique cocktail of reasons—pushing us out from the inside and pulling us out from the outside—to log off for a long time.

The internet was an amazing idea that, over time, redefined society in a way that made it hard to relate to pre-internet times. It turned out to be even more amazing than its creators could have predicted. But it seems we can’t have nice things. Thirty years is not a long time. We feel there won’t be a future without the internet because it’s all there is now. But we lived without it once.

We like to say tech only improves lives but not all innovations do so to the same degree. Some innovations we think are cool are discovered to be very harmful in retrospect (like cigarettes). The physical world, with all its flaws, is feeling much more appealing now. The early days of the internet were beautiful. It was posited to be an escape from the harsh, crude real world for non-fitting people. It was a place to hide from our monsters. Now the monsters have followed us here. And they’ve had children. And their children have had children of their own.

Now the real world is the escape. It’s where we go to find calm.

It could very well be that the internet, for all its indubitable value, and as seamlessly integrated as it is today, won’t be a piece of our future. The great digital exodus might not happen as cleanly and clearly as I’m describing here, but we’re no longer lacking reasons to disconnect, perhaps forever.

One of your best, Alberto. I enjoyed it tremendously. Perhaps you were closer to home in the opening, though. Even though the internet is largely corrupted it is difficult to see it disappear altogether. What we are seeing is further fragmentation and evisceration where much of the internet lays is ruins but other parts can continue to exist in isolation: like Substack and like some useful things you can still do online even when so much of the original communal aspect is gone

This was a beautiful, nostalgic, painful read. But in a way, it makes me more angry. I assume that although there could be a Great Logging Off, there will still be enough fondness or utility to use social media sparingly. Even if not, the infrastructure will still exist, and if either DIT or Boring Apocalypse is correct, it means that we are wasting obscene amounts of resources that we can't afford to waste, all on a demented simulacrum that is kept alive likely because economists will decide it still Generates Value. Plus, the infrastructure will still allow corporations and governments to monitor your every move, even if you no longer participate to any extent - not playing does not turn out to be a winning move in this case. Ceding that territory, however toxic, feels just as much a mistake as holding ground there.