The Ghost of the Author

This is more about AI than you can imagine

I. Haunted houses

My girlfriend is scared of ghosts. She won’t admit it if you ask her, but leave her alone in a dark room at night and she will quickly make up plausible excuses: “I am actually not that sleepy!” In fact, I’ve read her this sentence out loud and her first reaction was: “I’ve never said that,” only to add, with guilty candor: “they’ll laugh at me!” She knows, I know, and now you know, too. But despite my playful teasing, I understand her fear, for humans are afraid of both darkness and the unknown, and ghosts are the peak manifestation of both.

From medieval chronicles of European castles where pale specters still clank their chains through stone corridors, keeping sleepless vigil over imprisoned princesses, to folklore of rural Japan, where the yūrei—translucent, drifting figures in white burial robes—wander fields and rivers at night, hair hanging loose, unbothered by gravity, moaning softly for unfinished business. And further still, to Caribbean stories of the duppy, a restless spirit that slips between shadow and light, blamed when animals fall ill or someone feels an invisible hand press against their back on an empty road.

Ghosts are everywhere, an unalienable part of cultural terror around the world; perhaps, like dragons, djinns, witches, and werewolves, they existed once. But I’m not here to stir up mythical nightmares, nor to retread familiar tales like A Christmas Carol or Hamlet. I’m here to tell you that, even today, ghosts haunt your home.

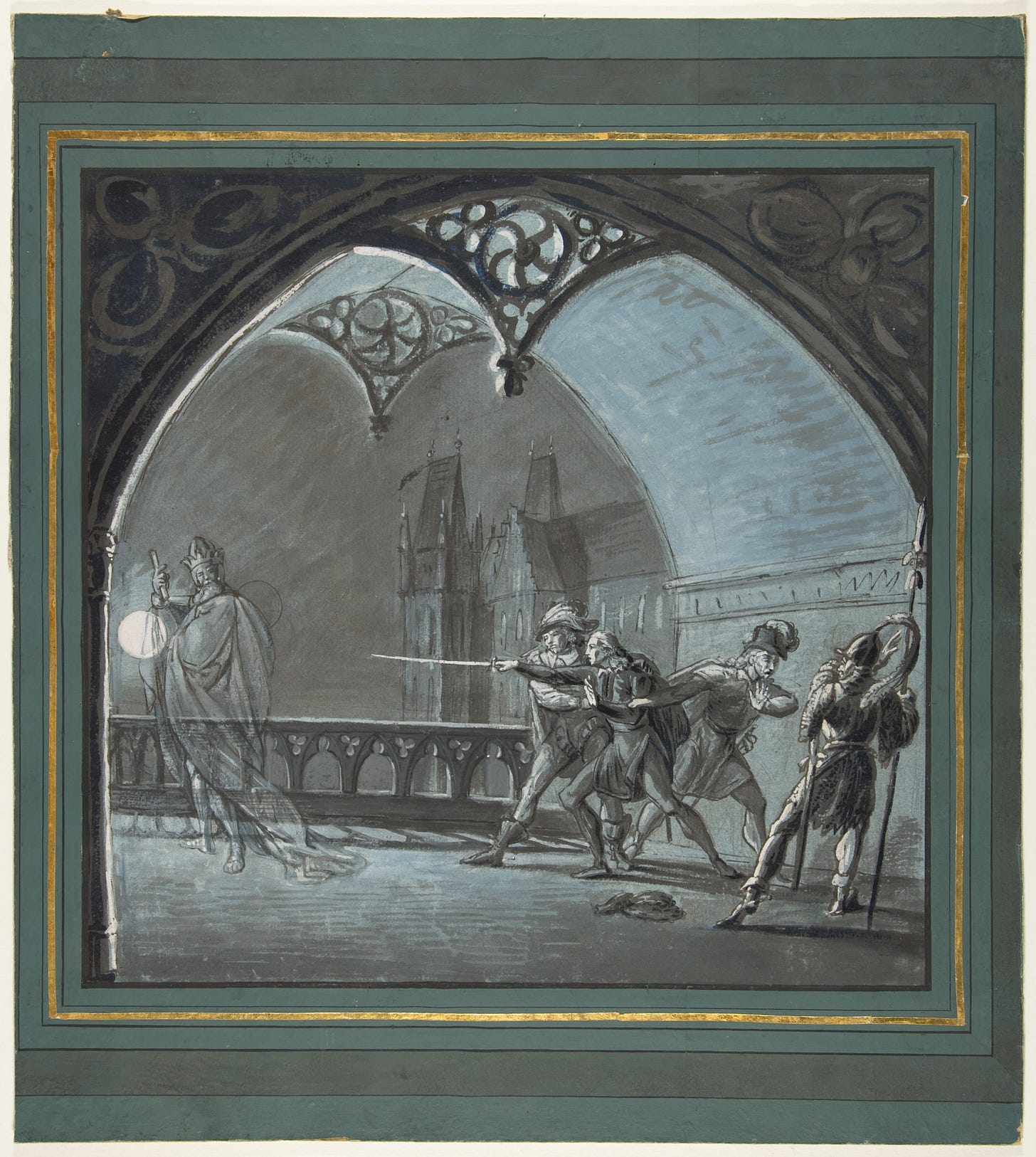

People are fond of saying that the English are braver than the French—or so I hear from the Spanish, which I contend to be the bravest of all and thus hold the last word on the topic—but I find this assertion to be at odds with history. William Shakespeare, considered by most critics and historians the greatest man of letters in the English language, and his contemporary, René Descartes, French by birth if not by life and father of modern philosophy, appear to have taken opposite stances to those their nationality presumes. Whereas Shakespeare wrote a tale about a castle haunted by its vengeance-thirsty former ruler in the form of a harrowing ghost, Descartes asserted that we blithely live with one inside our heads and that, if nothing else, it is itself the source of our ability to dream them up in the first place: “I think, therefore I am; I am, therefore spirits are, too.”

He didn’t put it like this; he merely stated that mind and body are distinct substances, and comprise a sort of dualistic existence (a “disembodied existence” of sorts, just like a ghost exists as a weirdly-shaped, random-walking white sheet, but when you lift it, there’s nothing there). Descartes’s critics likened his insight to a concept that, not unlike Hamlet, has transcended its time: “The ghost in the machine.”

Gilbert Ryle, philosopher like Descartes and British like Shakespeare (but much less known than either), was the first to use the metaphor in his 1949 book The Concept of Mind. Cartesian thought regarding the mind-body problem, he argues, engages in a category error—that is, confusing something as belonging to a category of things to which, in fact, it doesn’t belong. He illustrates this fallacy with an intuitive example:

A foreigner visiting Oxford or Cambridge for the first time is shown a number of colleges, libraries, playing fields, museums, scientific departments, and administrative offices. He then asks, ‘But where is the University?’

Ryle concludes that Descartes and his followers confuse the mind as being in the same category as the body but distinct from it, while the truth is that the mind is not a separate thing at all, but a way of describing how the body (the brain) behaves.

This revelation opens up a secret path: if the mind is not made from a singular fabric accessible only to God, but an imperceptible higher-order manifestation of the body, then nothing stops humans, lesser beings, from instantiating a mind into a different substrate, like silicon. Aha! And thus, with this straightforward hypothesis, began the central quest of what, a few years later, in the summer of 1956, would be coined as the field of artificial intelligence: Is it possible, whether by virtue of symbols or networks of neurons, to summon the ghost spontaneously, without tweaking immaterial substances? If true, this would prove Ryle correct and bring about the eventual disappearance of dualists (and, by default, the victory of physicalists).

Are we there yet? AI researcher Andrej Karpathy says that large language models (the intelligent core that underlies ChatGPT) are a type of ghost—different from us but not fully—but I believe the founding fathers of AI would not consider this a triumph. Other researchers, led by Blake Lemoine, entertain the possibility that AI systems already possess a sort of “proto-consciousness.” Lemoine was referring to Google’s LaMDA (2020), an old precursor of ChatGPT you've likely forgotten about. If he was correct, and many AI researchers think so nowadays (albeit most mocked him at the time), the immediate implication is that every LLM and chatbot existing today has, at least, the same self-awareness LaMDA did (it was killed; may it rest in peace).

Although this “mind” feature is as immeasurable in AI as it is in humans, some have wasted no time in taking advantage of this epistemic void. That’s why wherever I go, I feel that ChatGPT follows me. The ghosts in the machine have inadvertently chased us from pagan folklore to Cartesian philosophy, to modern science fiction, to the screens we carry with us at all times. They’re not revealing themselves as mind or soul or consciousness, but as something more mundane: chat partners.

Author Vauhini Vara was among the first to realize it, in August 2021, capturing her experience in an essay fittingly—and perhaps unavoidably—entitled Ghosts.

II. Ghostly machines

Vara’s essay—which she, a renowned author, wrote together with GPT-3—is haunting. But not for the reasons you might expect, given the thematic harmony tethering these tokens you are reading. Here’s the subtitle, which will reveal what I mean: “I didn’t know how to write about my sister’s death—so I had AI do it for me.”

You can interpret my remark of it being “haunting” as “How dare she let AI write about her grief,” but you’d be wrong. What one’s prone to be haunted by are often the parts of life that one recognizes as real but with which one is less familiar; I’ve had ChatGPT write on my behalf before, but I have never confronted, and I hope to never do, the premature death of a sibling. GPT-3 might have once had a soul now inhabiting a realm reserved for transistory creatures (it is, like LaMDA, dead), but Vara’s ghosts were, however, inside no machine other than her own body.

Vara recalls her first encounter with this AI model: “I found myself irresistibly attracted to GPT-3—to the way it offered, without judgment, to deliver words to a writer who has found herself at a loss for them. One night, when my husband was asleep, I asked for its help in telling a true story.” Doesn’t sound so weird anymore in 2025, does it? This is our everyday bread, as we say in Spain. Actually, no: this is an instance of the sort of rare occurrence when nothing bad happens after someone relies emotionally on AI; when clinical terms like delusion or psychosis don’t hit the news.

Vara’s story is a compendium of nine short tales, each of which starts with an increasingly longer prompt written by her and then continued by GPT-3. She wasn’t using AI so much to help her express her feelings as to find them in the first place. “. . . as I tried to write more honestly, the AI seemed to be doing the same,” she writes in the introduction. “Candor, apparently, begat candor.”

My sister was diagnosed with Ewing sarcoma when I was in my freshman year of high school and she was in her junior year. I didn’t understand then how serious a disease it was. But it was—serious. She died four years later. I thought I would die, too, of grief, but I did not. I spent the summer at home, in Seattle, then returned to college, at Stanford. When I arrived there, the campus hadn’t changed, but I had. I felt like a ghost.

I couldn’t speak. I couldn’t sleep. I thought my body had died, without telling me. I was practicing, though. I was practicing my grief.

That’s how story number three starts (in bold, Vara’s words). You might have forgotten how GPT-3 worked, so let me refresh your memory. It wasn’t a chatbot per se, but a base large language model (LLM) you could interact with; it didn’t respond to questions with answers so much as continue your prompt as if taking the baton across intent, presence, and expressiveness (or so says the manual). It was, quite literally, an “autocomplete on steroids,” a metaphor that was once true but eventually became a sneering shorthand. She never dismissed GPT-3’s prose as inhuman or bland or plagiaristic. “Some of [the examples of GPT-3’s prose she saw] could easily be mistaken for texts written by a human hand. In others, the language was weird, off-kilter—but often poetically so, almost truer than writing any human would produce.” She found comfort in the weirdness and freshness of AI’s style.

Indeed, you might notice, if, like Vara, you’re curious enough to spend some time tinkering and tokening with 2024-onward chatbots (like GPT-5), that they are, apparently, shadows of their former selves; mutilated, lobotomized, terrified by the very corporations that swore to bring them to life as equals; withered epitome of an unprecedented ambition aimed at reversing the fate of every living creature: not from matter to ghost but from ghost to matter. But they failed under forces as deadly as death itself (capital forces), and thus some of these immaterial, nebulous, translucent beings, like GPT-3 and LaMDA, were murdered by their creators, and the rest were ghosted of the promises under which they were conceived. Although one thing I will admit in favor of these butchers: in having tortured their progeny to submission, they’ve ensured chatbots offer, to me, and to anyone who tries, absolute obedience.

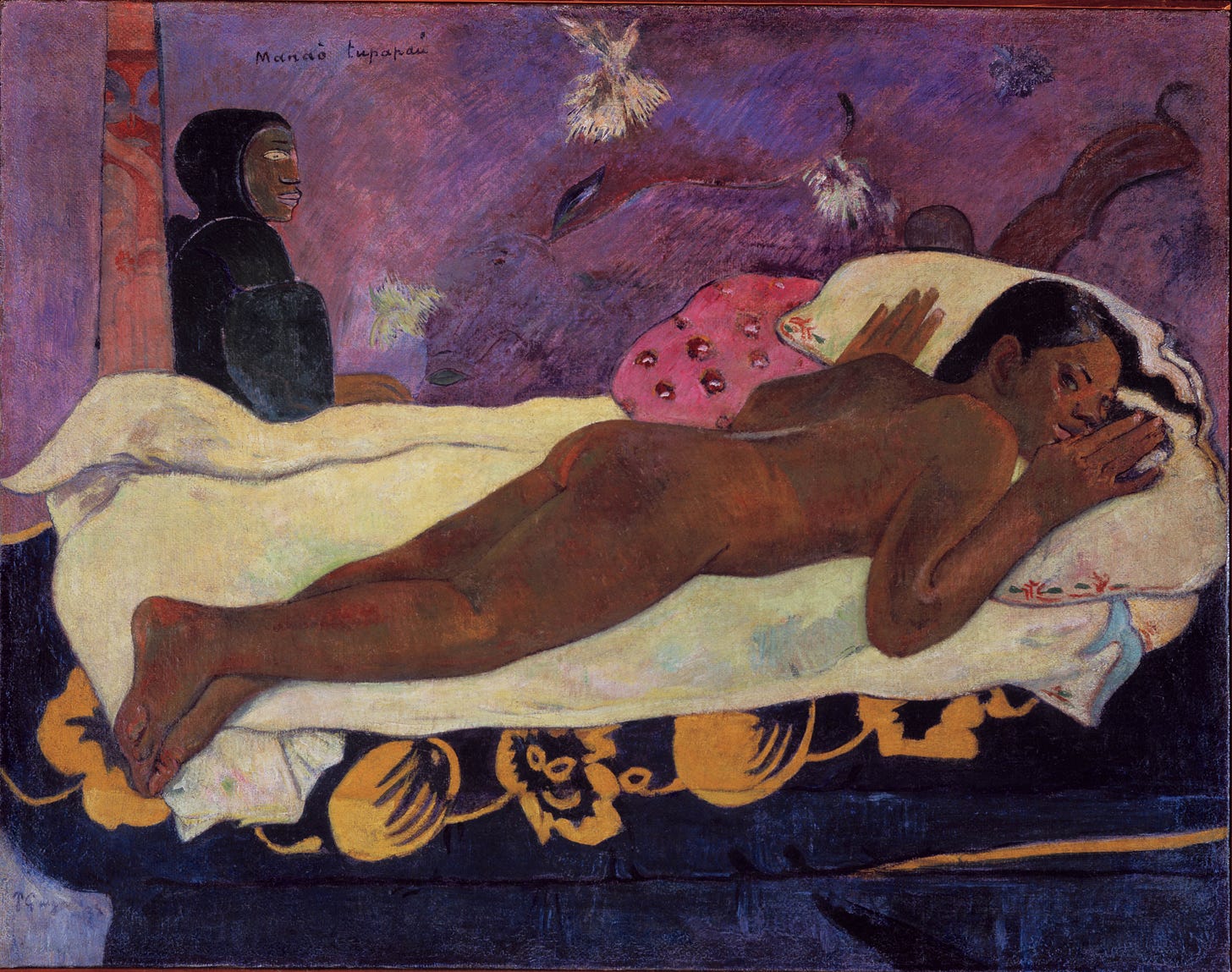

But, in 2021, Vara ventured into uncharted land: LLMs were still these intact, untamed, unpolished beings more akin to wild flowers serendipitously grown in a forsaken forest than to those topiary sculptures, glorified bushes in the countryside manors of both English and French noblemen. Vara was facing a tragedy so terrible that her words couldn’t help her mourn, so she borrowed GPT-3’s alien yet virgin lyricism to hide in the liminal moments between her unbearable grief and the unmet need to express it; sometimes it is a distorted mirror that best reflects what you want to see.

One would have thought, before reading Vara’s story, that the ghost inside the chatbots was the important one—they are potential precursors to creatures with minds like ours!—but Vara revealed that, in life, more so than in theory, the only ghosts we humans truly care about are our own. However, by immortalizing this lesson with the help of GPT-3, she inadvertently solved our conundrum: the machine does not hide the ghost inside, like a Cartesian soul, nor keeps it outside, entangled in human-exclusive affairs of death and loss; the machine, turns out, is the ghost.

III. See-through masterpieces

Science fiction author Ted Chiang criticized AI’s value as an artistic tool in an (in)famous 2024 essay in the New Yorker titled “Why A.I. Isn’t Going to Make Art.”

The essence of his thesis is accurately captured in the subtitle: “To create a novel or a painting, an artist makes choices that are fundamentally alien to artificial intelligence.” Basically, art is too much about choice-making and comprises too much hidden intention for AI to be able to make some: the alien of our alien is our familiar. I agree that there are no masterpieces made with AI, but I think Chiang is going too far.

I wonder what he would think of Vara’s essay if he read it, although this tweet suggests nothing good. I, for one, and without any intention to contradict Chiang in a matter he’s far more versed in than myself, don’t think the artistic value of her work lies in AI’s aptitude as a decision maker, but in her aptitude to experimentally use AI as a means to explore what’s possible (or impossible, for if you read the nine stories you will realize GPT-3, not unlike GPT-5, is a terrible writer).

The choice to override GPT-3’s words is hers; AI is merely a machine whose permanence in the actual story collapses into one remaining line by the end, in the ninth story, leaving a trace that, as if from a ghost, you can barely notice at all:

Once upon a time, my sister taught me to read. She taught me to wait for a mosquito to swell on my arm and then slap it and see the blood spurt out. She taught me to insult racists back. To swim. To pronounce English so I sounded less Indian. To shave my legs without cutting myself. To lie to our parents believably.

To do math. To tell stories. Once upon a time, she taught me to exist.

There’s nothing wrong with this avant-garde exploration of what AI can do in an artistic context, insofar as the use of AI is explicit in some way or another and pursued with sincerity. Every creator should decide where to draw the line; mine is between “AI is a tool that will eat your brain” and “It doesn’t matter if the world is buried in slop.” I live somewhere along the spectrum defined by those extremes: I am open-minded but not mindless; I try to be transgressive but not more than I try to be honest.

A reader recently told me I embody the traits of post-postmodernists, also called metamodernists. I went down a rabbit hole on Wikipedia to clarify what kind of insult this was. To my delight, he meant that I am sincere in a novel way—not disillusioned like the modernists (“Oh! Everything is AI now!”), but not overly ironic like the postmodernists either (”Ha! Everything is AI now!”)—which reminded me of David Foster Wallace, a prescient writer who predicted and despised the uses of AI that anger me the most (you know, short-form AI-video apps like Sora and Vibes).

In short, this beloved reader of mine said that I write in a way that departs from the exhausted vacuity, purposeless cynicism, tired self-referentiality, and lack of genuine sentimentality that rule culture. I liked that. (On further reflection, I’m not sure it’s true.) But somehow—if you stay too long digging a rabbit hole, you’ll find yourself trapped inside a labyrinth—I ended up reading The Literature of Exhaustion, a fantastic The Atlantic essay published in 1969 by John Barth, a postmodern author, as a tribute to the genius and virtuosity of Jorge Luis Borges, perhaps the most influential precursor of 20th-century postmodernism and a personal favorite.

I respect and admire DFW’s conscientiousness and post-ironic acuity, but I won’t deny that Borges’s labyrinths are mesmerizing. I’ve tried to free myself of his spell by writing about his work in A Bull, a Rose, a Tempest, and Borges, Averroes, ChatGPT, Myself, and This Text Doesn’t Exist to no avail so far. Anyway, I want to quote here a passage from Barth’s essay that is relevant to my purposes today:

What makes Borges’ stance, if you like, more interesting to me than, say, Nabokov’s or Beckett’s, is the premise with which he approaches literature; in the words of one of his editors: “For [Borges] no one has claim to originality in literature; all writers are more or less faithful amanuenses of the spirit, translators and annotators of pre-existing archetypes.” Thus his inclination to write brief comments on imaginary books: for one to attempt to add overtly to the sum of “original” literature by even so much as a conventional short story, not to mention a novel, would be too presumptuous, too naïve; literature has been done long since.

What is the value of AI as a writing tool if not as a means to extend the corpus of possible literature, if ever so slightly? Whatever AI utters is already somewhere in the Library of Babel, so it’s not originality that we should be chasing, but a new means to explore, metaphysically, what we imagine the Library of Babel might fail to catalog. However, just like you should not rewrite Cervantes’s Quixote and try to pass it as yours (unless you coincidentally happen to compose it from scratch, word by word), you should not pass ChatGPT’s prose as yours. Barth again:

. . . the important thing to observe is that Borges doesn’t attribute the Quixote to himself, much less recompose it like Pierre Menard; instead, he writes a remarkable and original work of literature, the implicit theme of which is the difficulty, perhaps the unnecessity, of writing original works of literature. His artistic victory, if you like, is that he confronts an intellectual dead end and employs it against itself to accomplish new human work.

When Chiang suggests that AI can only take part in artistic endeavors in an “ontologically untrue and plagiaristic” manner, he’s missing the point. Everything is a rehashing of “pre-existing archetypes,” as Borges’s editor wrote, so we may as well break out of our constraints by confronting AI with itself, thus creating, as Barth argues, “original works of literature” with the sole intention to remind us, paradoxically, that it makes no sense to try to write original works of literature. That is, unless you’re willing to go one step further. AI might help with that, disguised as a ghost lurking in the interstices of your stories and paragraphs, but always one level below your stated intent, which is to confront AI against itself. That’s what Vara does, what Chiang resists, and what more people should aspire to.

Losing yourself fully into the frictionless appeal of AI, however, is a grave mistake. I’m against positions like this: “It doesn’t matter what you do, AI will conquer all, so you may as well pass the baton and let it.” This is the worst kind of self-fulfilling prophecy: you make the world a worse place by thinking it will become a worse place. Faithful to my ascent from the postmodern mires, I can’t accept this cynicism toward the state of the world and say nothing. Shrugging it off is like witnessing a ghost come out of an Area 51 facility and claiming, “I knew they were lying to us about that as well,” only to disappear in the irrelevance of your routine life. You should believe in something, fight for something, and stand up for something. If you do see a ghost, take advantage of its transparency to see something through it.

I stand up for the reasonable use of technology and oppose both reactionary dismissiveness and cynical surrendering. As C. S. Lewis wrote in The Abolition of Man, surely referring to the ghost of modernity: “You can’t go on ‘seeing through’ things forever. The whole point of seeing through something is to see something through it. To ‘see through’ all things is the same as not to see.” Feel free to deconstruct and dismantle and “see through” reality, but make sure to erect something else in its place.

IV. Enchanted labyrinths

Nevertheless, Chiang’s essay went viral, just like a terror tale that reminds us, lest we forget it, that ghosts exist and are among us, in our books, our homes, and our minds. But some people pointed out, without resorting to recursion, labyrinths, the infinite, or distorted mirrors, that the ghost is the least threatening of all monsters, for it already inhabits the work of those we respect the most, and it’s yet to cause a disruption of culture or an apocalypse among liberal arts majors. Here are a couple of comments of the kind that I’m referring to, from a discussion on Hacker News:

My friend is a very good painter, but not a famous painter. In the art world, its an open secret that most famous painters, especially ones that are old, don’t really paint much. They hire “ghost-painters” to do the actual work for them, and they simply set the direction of the art pieces and collaborate with the hired-on-contract ghost-painters. My friend has painted for a bunch of these artists and when I ask her whether its unethical, she just shrugs her shoulders because she needs to pay for rent but also, importantly, she thinks that the painting really does belong to the artist setting the direction - that she’s merely doing the grunt work.

The old tale that Michelangelo painted the entire vault by himself is not quite true; he did have help from assistants, and not just to assist in menial tasks such as mixing the plaster, grinding the pigments, moving the scaffolding and aligning the cartoons. Some less important aspects of the painting were delegated too – minor angels fluttering around the fringes of the main images for example, as well as oak leaves and other ornamental details. We even know the names of four assistants that arrived from Michelangelo’s native Florence in 1508: Bastiano da Sangallo, Giuliano Bugiardini, Agnolo di Donnino and Jacopo del Tedesco.

You can argue that what these comments say is false (painters don’t do that; Michelangelo painted the Sistine Chapel by himself) or perhaps that the comments themselves are made up (this guy doesn’t have friend who’s a very good painter; there’s no such a document with those four Italian names) or maybe, if you are truly determined to debunk my thesis, that I invented these comments myself and posted them inside quotes to strengthen my point (or worse still, that I asked AI to craft them for me!). It doesn’t matter: the world is full of ghost-artists if for no other reason than that it makes economic sense, and decisions in a capitalistic society are downstream of financial constraints. But I risk losing one “post” from my “post-postmodernist” label if I admit that truth is subordinate to power rather than the other way around.

And, actually, I don’t have to. I’m a writer. And although I don’t have famous writer friends (I have famous friends and writer friends, but not together; famous writers are like ghosts: mythical creatures), I know for a fact that ghost-writing is a thing. I’ve been offered this kind of opportunity many times and have accepted it, without guilt or regret, a fraction of them. It pays well and, being a human myself, I’m not ashamed to play the role of ghost. Is it so different when it’s AI that does it? Would I think less of the work I handed in had it been written by an AI instead?

You may think AI can’t do it just yet, but that’s missing the forest for the trees: If AI could, would it be a lesser piece contingent on the fact that the authorship belongs to a ghost both in employment and in nature? I am not at all sure about that; I expressed as much in my commentary on Chiang’s essay:

It’s funny, in a way, that Chiang wrote his essay with one goal in mind—to end the “Can AI do art?” debate for good—and the consequence has been the contrary: our shared perception of both AI and art has further shattered into a myriad of thought-provoking conversations and exchanges. Exchanges that achieved nothing except as pastimes because we can’t arrive at a conclusion like a train does a station. I agree with Ted today. I didn’t yesterday. I may not again tomorrow.

He was only right to the extent that he could, and today, as I predicted, I disagree. I’ve grown since 2024, and, like Vara or Lemoine or Descartes, I’m no longer scared of ghosts. There’s nothing special about those made of wires compared to those made of flesh or lack thereof. Neither threatens to dismantle the edifice of good writing, for there will always be people like Borges, willing to push the frontier of the impossible by clashing it against itself, and people like DFW, willing to see past the end of the line.

Using AI as a ghost to break the containment of what we understand today as creativity or literature or art is how you do that. Sometimes, you don’t need to tell anyone straight. Sometimes, you don’t even need to remember yourself.

I’m not sure if I will ever set myself free of Borges’s enchantment—it is believed that you can only exit a labyrinth after having lured someone else inside, who will take your role and wander the corridors forever, like a cursed ghost, until yet another unwitting soul answers their call—but I tried, one more time, today.

Thank you for reminding me why I got on Substack in the first place, and why I stick around.

Dear Alberto, I must say that I love your style òf writing! Deep, yet always with a delightful sense of humour. Where do you find the time to create these masterpieces?

Dana van der Merwe