The Human Toll of Waiting for AI to Take Over

More robots, please

So much time thinking about AI has changed how I see people. I notice the workers I used to overlook, doing the jobs no one wants to think about. Living in Madrid, that doesn’t mean miners or fishermen, but warehouse staff, delivery drivers, supermarket stockers, and cleaners. Like the worn landscapes of a city you’ve walked a thousand times, they fade into the background, part of the scenery. They blend in like mundane noise we drown out with premium headphones. They’re the subservient cogs in a system that feeds from them without giving back.

They’re everywhere, wheels of the world. They always were. I wasn’t looking. And that’s what unsettles me most: Not the shame of having ignored them blinded by the unspoken privilege of being a writer, but how unsurprising it feels that I did—does anyone ever think about them?

I do now. Or, at least, I do today.

I took a trip to the beach with my parents and my siblings in early December last year. It's the best time for that: empty shores, the cold softened by the tempering effect of the sea, and a sun that won’t dare scorch my skin. On the way there—five hours from Madrid, far by Spanish standards—we passed through one of the road tollbooths that separate the capital from the rest of the Iberian Peninsula.

No space is more liminal than a tollbooth. No worker is more forgotten than the one who sits in those cabins, idle. Pure in-betweenness. The perfect subject for my newfound habit of noticing.

Sure enough, there he was our tollbooth man, standing in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by nothing except abject indifference. He was waiting for us. He was waiting for anyone. That’s what I thought when I saw him lift his head toward the only car in sight for miles. We said hello. He responded, “Hello, it would be 13 euros,” with the detached politeness of someone who needs you but needs even more to keep his emotional distance from the quiet, heavy loneliness of his job.

We handed him the cash. As he counted it—at least twice, only to be sure—I took a glance at his office: a computer screen with no movie playing, an uncomfortable-looking chair, a photo of three people in a frame, a few illegible post-its. He also had some extra change he had pilled up within reach, more a sign of the wish that another car would pass by soon than a carefully designed approach to conduct his Danaidean mission with efficient diligence.

The barrier lifted and we drove on. One last thought crossed my mind: this is his life. Day after day, hour after hour, minute after minute. Dark sonder. The pure desolation of it all overwhelmed me. Thank goodness the beach awaited us, with the same balsamic power we had granted, just for a moment, to the wretched tollbooth worker.

During the rest of the trip, I did not give him another thought.

Until now.

Why does that man have to be there? Why aren’t all tollbooths unmanned by now? Wouldn’t he be better off doing something else less isolating and more fulfilling? Or would he resent the idea, seeing it as yet another case of automation stealing a livelihood? I don’t know. In a few years, it won’t matter—he will be automated.

Thinking back to that framed picture in his tiny office—him and two kids smiling ear to ear—I’m certain that our tollbooth worker will welcome his fate.

Or am I? It is easy to rationalize the immense value of automation from my dispassionately comfortable chair at home, typing away on a computer where I can watch a movie if I want to—whenever I want to—while I make money from delicately placed words. It's not so easy when it’s you that automation is coming for.

Perhaps my worst sin is believing that I know him just because I have taken the trouble to write this. Aristocratic condescension.

Automation is, coincidentally, like a trip to the beach: before it happens, it feels great looking at the holidays approaching on the calendar and, after it happens, it feels great swimming in the warm waters of the Mediterranean. But it's a hassle having to go there by car, for five hours, and queuing in front of the damn tollbooths.

The transition is terrifying; the uncertainty, irritating; the pressure to adapt and reorient plans that took decades to build, burdensome.

I’m safe today. My grandchildren will be even better off in 50 years. But what about the in-between?

No one cares about the in-betweens like no one cares about our tollbooth worker. You and I do today. We won’t tomorrow. He lives in liminality, a passageway to all possible vacation destinies. He’s a fleeting protagonist at this moment but will be gone the second you close this page. He’s forever trapped, unable to find peace at either end of the road; unable to enjoy that empty shore.

I was grocery shopping with my girlfriend earlier this year, picking up something for Valentine’s dinner along with other stuff like toilet paper.

No one ever writes about toilet paper yet we all use it every day. Isn’t that one of life’s little ironies? It becomes strange indeed that it hasn’t taken its place, as Virginia Woolf would say, with love and battle and jealousy among the prime themes of literature. Or maybe not so strange. After all, it’s just a liminal object. A transition between sitting down and standing up. As George Orwell once wrote, novelists have a knack for ignoring the things that make the wheels go round. Like toilet paper. Like tollbooth workers.

Anyway, as we walked through the bathroom aisle to grab some pH-neutral detergent—I have atopic dermatitis, which I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy—I saw a worker on a ladder, unpacking things from a big brown box. Bottles of detergent. Dozens. One after another, she was placing them on their corresponding shelf. It was hypnotic. Perhaps even more to herself than to me.

I looked at her face. I wanted to see her expression. Just as I expected—more neutral than the detergent we were shopping for. A blank stare. Mechanical movements so standardized I’d swear they had been measured with a tape. She was almost a robot in human skin Except she wasn’t. She was a real woman with feelings and everything, probably long crushed under the unbearable irrelevance of her task.

For her sanity’s sake—if there’s any left—she has surely forgotten this moment I’m recalling in painful detail here. That aisle worker, like the tollbooth worker, was another hidden link in the chain of unsuspecting convenience that underpins modernity—the kind of convenience science fiction only hints at, more interested in grand visions than the quiet ease of a stocked store. Futurist cinema reflects just one possibility from the countless counterfactuals we brush past every day. We expected moon colonies, cybernetic implants, and flying cars. We got aisles full of detergent, 24/7. And barriers that lift, as if by magic, so that you can go to the beach.

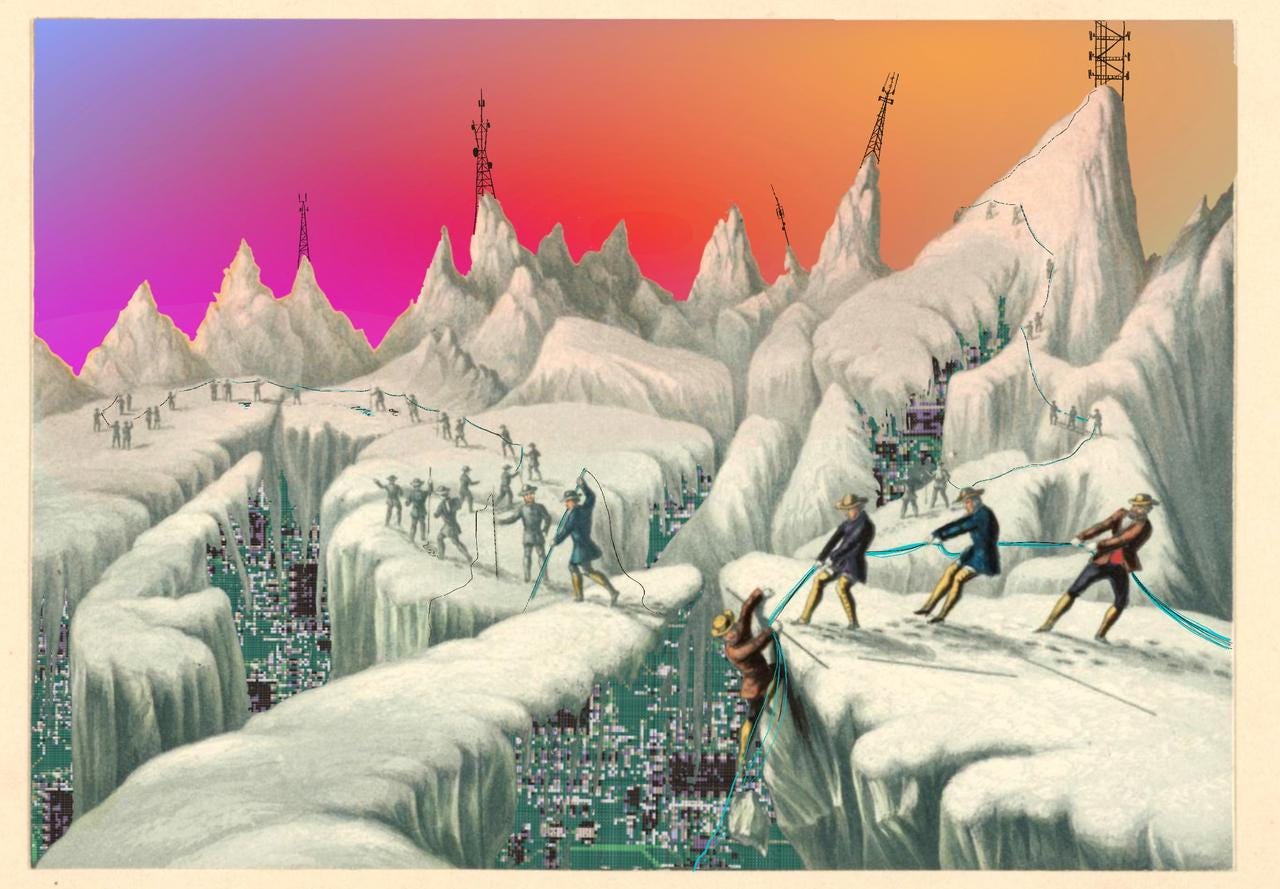

In this universe of iPhones and ChatGPT, automation has not reached every corner. It remains unevenly distributed. So for now, she and he will stay in their jobs, impassive, invisible to a society that needs them yet ignores them. And waiting, whether they realize it or not, for the promised robots that never seem to arrive.

This is not the future that Isaac Asimov predicted fifty years ago. It is but a heavy toll they unknowingly endure.

I came back yesterday from a quick trip to León. Two hours by high-speed train. A dream. No cars, no tollbooths. But—bourgeois as we middle-class workers have become—I still found myself cursing the traffic on the way home from the station, grumbling in the back seat of an Uber. The train had arrived at the worst possible time: the end of the half-day work shift, when the whole city floods the streets to go home for lunch. A trip that should’ve taken 15 minutes dragged into 40.

Isn’t it strange that, despite all the comfort of the 21st century, traffic still grinds to a halt? Like everyone else, I feel that phantom jams haunt me. Every slow crawl through a packed avenue sparks the same exasperated thought: Why are there so many people on this planet? Can’t they all just go on vacation to the beach and leave me alone?

No, they can’t. The tollbooths would clog, choked by the annoying insistence of tollbooth workers to drag out—whether by chance or by need—the inevitable farewell of their transiently pleasant visitors. And the market aisles would be empty, leaving those otherwise tranquil coastal villages looking like a scene from the peak days of the COVID pandemic.

But I won’t curse anymore. When I find myself stuck in traffic, caught between a bus full of tired faces and an Amazon delivery truck with more haste than an ambulance, I’ll take a long breath and thank them. All of them. They—whom I will only briefly cross paths with in a traffic jam to never meet again—are also lost links in the proverbial tollbooths and aisles I take for granted.

The convenience of taking long beach trips, buying pH-neutral detergent, and riding high-speed trains only exists because there are this many people on the planet. We seldom notice them except when they’re blocking us from getting to our destination, either as a tollbooth worker who isn’t handing the cash quickly enough, the aisle worker who’s placed the products on the wrong shelf, or the car in front of us, unnecessarily changing lanes.

The rest of the time, when we don’t bother noticing, they make it all run as smoothly as it’s humanly possible. But, as conscious humans, they are also the kind of cog that wish it wasn’t a cog.

So I dedicate one more instant to him and her: Wherever you are, I hope you are robots now. I hope all the people who were stuck with me yesterday in that traffic jam are robots, too. That's the least I can wish for you.

That’s the least I can wish for myself. I like to do this work of mine that’s not so distinct from that of a medieval alchemist: I take either black ink or null RGB pixels and by placing them in inscrutable patterns on paper or a screen, I turn them into money. The other Isaac, Newton, would be proud of me. But, as grateful as I am for having been born a wizard, I still have to do this for money.

Why can't I just scribble some contemporary hieroglyphics for pleasure and live, as Asimov wanted, like an aristocrat? Why can’t the tollbooth worker become a painter drawing inspiration—not melancholy—from his two young boys? Why can’t the aisle worker regain her smile by becoming a sculptor who, like the market shelves, seeks each item to find the perfect place but, unlike those sterile shelves, does not pursue optimized repetition but craftsmanship?

So, having noticed what I now tell you, how could I be angry at the people building robots and intelligence imprinted into silicon when they are, however selfish their motivations, the ones trying to automate the world into something resembling an earthly utopia? I can’t. They, too, are overlooked links in the chain. Working in research, development, design, and distribution. But unlike the others, they’re leading a revolution. A revolution that you too will welcome, once it forces you to see what, in the absence of a habit of noticing, you have long ignored.

I only ask these aspiring revolutionaries to pay attention and deep consideration—not just today, like I do, but always—to the transitory, liminal spaces. And the ones who dwell there.

It’s amazing how you mix philosophy and mundane things—altogether with AI. Good one!

I’ve been doing a similar thing all the time when “out in the world”. My thoughts are always questioning similar things. Are they aware of what is coming? Do they realise how much the world which change soon? Where do they think they will be in 5 years time? Do they realise that they could access a super smart assistant at anytime anywhere right now?

These are peculiar times, and it really does feel like we are all at a toll booth waiting to see if we will continue towards our next destination…