Sam Altman Is the Christopher Columbus of Our Time

Hey guys, today we’re doing something special: I’m having a fellow Substack writer over at The Algorithmic Bridge. M. E. Rothwell is the author of Cosmographia, a newsletter that explores the world via history, geography, astronomy, and mythology. Right now, he is in the middle of an ongoing series about Christopher Columbus.

He asked me to cross-post his essay on Columbus and Sam Altman—where he draws some uncanny parallels between the two—and I immediately said yes. You guys are going to love it. I won’t spoil the surprise, but I’ll say it’s a magnificent example of that aphorism commonly attributed to Mark Twain (possibly apocryphal): History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes.

Paul Graham, legendary Silicon Valley investor and co-founder of Y Combinator, once said of Sam Altman, “You could parachute him into an island full of cannibals and come back in five years and he’d be king.” Such, according to Graham, was his “force of will”.

Graham’s description is reminiscent of another man with an iron resolution: the infamous Genoese explorer, Christopher Columbus, who in the early 16th century found himself in almost exactly this scenario. In 1503, on his fourth voyage to the Americas, Columbus became marooned on Jamaica after months of storms and woodworm had all but destroyed his ships. For an entire year, he survived that island, despite a mutinous crew and growing hostility from the native Taínos, who he claimed “ate men” (whether they were truly cannibals or not remains disputed). Such was Columbus’ unpopularity by this stage of his career that his fellow conquistadors on the nearby island of Hispaniola, upon hearing of the Genoese’s predicament, dallied for 12 months before sending a rescue party. Stricken with agonising gout and barely able to walk, Columbus survived two rebellions among his men and managed to thwart the Taíno attempt to starve him out. The locals did not make him king, but they came to believe him a servant of divine wrath after he used a lunar eclipse to terrify them into submission.

Since ChatGPT’s release in late 2022, and the ensuing explosion of interest and investment in artificial intelligence, much has been made of the man who has become the face of this emerging technology. But, as Alberto Romero has written, you cannot hope to understand Sam Altman, or any of the other AI builders, with an ordinary theory of mind. They are not ordinary people, motivated by ordinary concerns. Instead, they are more like Columbus.

The first and most obvious similarity between Altman and Columbus is that they are both frontiersmen.

Today, AI is the hottest field in the world, but a mere decade ago, when OpenAI was first founded, few could have predicted its takeover of the tech industry. Perhaps the most serious organisation operating in the space at the time was DeepMind, whose early successes training neural networks with reinforcement learning to play video and board games saw them get acquired by Google in 2014. At that stage, neural networks were little known outside of the space, and though promising as a domain of research, most of those in Big Tech weren’t sure how it could fit into existing business models. Indeed, Facebook passed on the opportunity to purchase DeepMind, and Google themselves were caught sleeping on AI less than a decade later, despite the fact that they had all the pieces necessary — the talent, the unfathomably deep pockets, the integrated tech stack — to emerge as the industry pioneer years ahead of the rest. Instead it was Altman who saw further than most when he pivoted OpenAI from a non-profit AI research lab into something more akin to a consumer products company in 2022, when he ushered in our era of generative AI tools with the release of ChatGPT.

In the years prior to this pivot, there were bold proclamations coming out of OpenAI about the possibility (and dangers) of developing superintelligence. These were, outside of the Valley and Rationalist community, treated with the same scoffs that greeted Columbus when he first proposed sailing across the Atlantic to Asia. The courts of Portugal, Spain, Venice, and Genoa ridiculed his plan and mocked the sailor as a crackpot. But both Altman and Columbus were proved right, if for the wrong reasons. Columbus never sailed to Asia, but he did open up the western passage to an entirely new continent. Similarly, while Altman has not yet come anywhere close to developing artificial general intelligence (AGI), he has with the launch of generative AI tools opened up an ocean of new horizons. Just as Columbus came to embody the European Age of Discovery, Altman has today become the face of the Age of AI.

Both men too were able to convince others to fund their far-fetched schemes. After nearly a decade of trying, Columbus secured the backing of the Spanish Crown for his voyage across the vast ocean sea, while Altman used his position at the centre of Silicon Valley’s venture capital scene to extract billions upon billions from a Who’s Who of Big Tech titans — Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, Reid Hoffman, AWS, Microsoft, to name but a few. To pull this off, both men showed a remarkable propensity for bringing others along with them, even on the most fantastical of dreams. To do so required an almost limitless well of self-belief, which both have in spades.

On his personal blog, Altman once wrote, “The most successful people I know believe in themselves almost to the point of delusion.” He might as well have been describing Columbus, who believed to the very depths of his being that God had selected him for a very special purpose. Altman again: “A big secret is that you can bend the world to your will a surprising percentage of the time.” If the phraseology had existed in 15th century Europe, Columbus would have undoubtedly been described as having the “reality distortion field” once attributed to Steve Jobs, and now to Sam Altman. The latter’s biographer, Keach Hagey, says one of the first things you notice about Altman “is the intensity of his green-eyed gaze, which he levels directly at you, as though he is speaking to the most important person in the world.” Columbus too had a blazing fire behind his eyes, which combined with his unshakeable conviction in the truth of his claims, enabled him to convince royalty that he might just be capable of achieving the impossible.

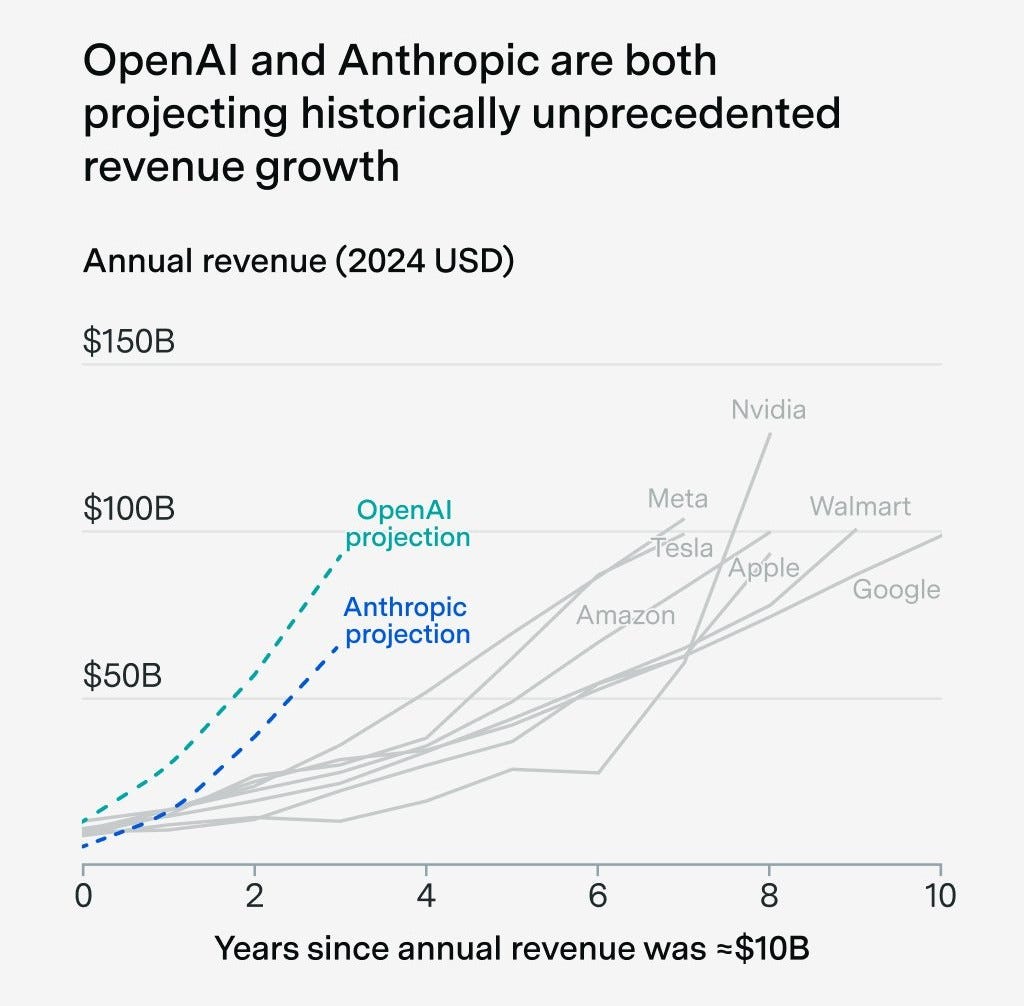

Likewise, in their respective adventures both men demonstrate an extraordinarily high risk tolerance: Columbus staked nothing less than his own life on his belief that it was possible to sail to Asia without a resupply, a feat everyone else at the time (correctly) believed physically impossible; Altman has committed OpenAI to over $1 trillion in future expenditure on the basis of a reported annual revenue of no more than $13 billion. The company’s entire future, and those of a myriad others now tied to the ChatGPT-maker in a complex web of deals, hangs on Altman’s ability to keep convincing the world that the speed of AI development will produce the fastest revenue growth in history. Neither do things by halves.

Columbus promised the Spanish Monarchs the riches of the East; Altman promises investors the greatest era of abundance in the history of humankind. Yet despite these assurances of great wealth, neither man is primarily motivated by money. Columbus was always driven by an overwhelming obsession with social status. His lowly birth, and the years spent being mocked by the nobility of the Iberian peninsula, made titles and prestige the lodestar of his ambition. He set sail for the East as a means of earning respect in the West (he found neither). Altman, meanwhile, has even less need for money. As he has said in interviews, he was able to take his position as CEO at OpenAI with no equity and a relatively modest salary because he was already rich – his previous investments have enabled him to accrue a net worth in the region of $1.9bn.1 Instead, he seems primarily driven by the desire to shape the future of humanity. He believes AI has the potential to be the single most important technology in the history of our species, and believes himself uniquely suited to usher in this vision of the future.2

But there’s a fine line between self-belief and a messiah-complex. Columbus was the sole survivor of a shipwreck in his youth. As he lay sputtering on the sands of a Portuguese beach, muttering prayers of thanks for his salvation, he began to believe God must have spared his life for some great destiny. In his later letters to the King and Queen of Spain, he assured them he would return from the East with enough gold to fund a crusade to retake Jerusalem. And in his personal cult of the Trinity, he believed himself — the Latin form of his name, Columbus, meaning “dove” — tasked with carrying the Holy Spirit across the sea.

Altman, meanwhile, is Jewish, though influenced by the Hindu Advaita Vedānta philosophical tradition. He once responded on X to the question, “What true thing do you believe that few people agree with you on?” with, “absolute equivalence of brahman and atman” — in other words, unity between the individual self and the ultimate reality of the cosmos.

In his communications as CEO of OpenAI, Altman doesn’t speak in terms which we’d ordinarily register as religious, but his belief in an imminent singularity — the moment technological growth accelerates beyond human control — suggests a deeply millenarian outlook. The singularity is heralded by “Doomers” like Eliezer Yudkowsky as equivalent to the Apocalypse, the Eschaton, the end of humanity. AI “Accelerationists”, meanwhile, prophesise that the coming runaway improvement in artificial intelligence will usher in a techno-utopia, an era of abundance where scientific progress is accelerated, diseases are cured, exponential economic growth becomes routine, interstellar travel is made possible, and perhaps even death itself is relegated to the pages of history. Regardless of which side of the debate is speaking, talk of the singularity reeks of the End Times — the same armageddon Columbus was hoping to usher in with the reconquest of Jerusalem — whence humanity will either be saved or damned, for eternity. Altman believes himself to be the one to lead us to the plains of Megiddo: “I think AI will… most likely lead to the end of the world, but in the meantime there will be great companies”. As the infamous Silicon Valley entrepreneur and investor, Peter Thiel, who has long been something of a mentor to Altman, told the Wall Street Journal, “We should treat him as more of a messiah figure.”

Some have suggested that Altman doesn’t actually believe all this to be true, but is speaking in such terms to ensure investors keep funding OpenAI’s infrastructure buildout, which when measured industry-wide ranks among the largest capital expenditures in economic history. Altman certainly has an incentive: if the money stopped flowing, OpenAI could well be toast. Detractors point to the accusations made by his fellow OpenAI co-founder, Ilya Sutskever, who claimed Altman exhibited a “consistent pattern of lying, undermining his execs, and pitting his execs against one another”.

Columbus too had a propensity to lie: on his first voyage he consistently lied to his crew about how far they had travelled — he feared they would demand to turn back if they knew how far they had sailed without yet sighting land. He only just staved off rebellion on that first crossing, but he wouldn’t be so fortunate on his third, when he was arrested, clapped in irons, and shipped back to Spain when his men grew weary of his inept management of Hispaniola. I’ve already mentioned the rebellions he later faced while marooned on Jamaica. This pattern of mutinies is reminiscent of Altman’s career too: engineers at his first startup, Loopt, at one stage called for him to be sacked; seven former employees of OpenAI walked out to found rival company, Anthropic, in 2021, over disagreements on AI safety; while most recently, OpenAI’s board of directors temporarily ousted Altman as CEO in 2023. Just as Columbus had troubles with fellow conquistadors Roldán, Bobadilla, and Ovando, Altman seems to have a knack for making powerful enemies. Among the many co-founders of OpenAI who have now broken with him, Elon Musk has attempted to sue Altman and his AI startup numerous times over the last few years. Overall though, Altman seems much better at surviving coups d’état than the Genoese navigator ever was.

One must wonder the degree to which these revolts were a result of the “by any means” doctrine that both men seem to share. Columbus was so determined to prove his discoveries were worthy of fame and celebration that his exploits on the islands of the Caribbean quickly turned dark. He enslaved the indigenous people, pressed them into delivering gold quotas, and mutilated those who failed to obey. Altman, of course, is not remotely guilty of anything so evil — there is absolutely no moral equivalence between the two’s actions. However, OpenAI’s alleged disregard for data ethics and copyright laws, as well as their form for having their voice-enabled chatbot impersonate a famous actor’s voice without her permission, does suggest a certain willingness to bend ethical boundaries in the name of progress. There is more than a whiff of the Machiavellian about the two men.

Of course, historical analogies are only useful up to a point. For all the similarities in ambition and spirit the two men share, there remain plenty of differences. Altman is far more competent a leader than Columbus ever was, far smarter, and far more adept at rallying people to his vision. But there is still one last comparison with Columbus that might be useful to consider.

The navigator never did concede that he hadn’t found Asia. His dogged persistence in his theories about the size of the earth meant he could not see that he had found something truly new in the Americas. He went to his grave blind to the truth staring him in the face. If, as some have suggested, AI progress is indeed slowing down, and it ends up acting as a fundamentally normal technology, will Altman be able to admit he was wrong about an imminent superintelligence? Or will he be like Columbus, and stubbornly cling to his vision of the future?

Columbus couldn’t see that he had found a New World; will Altman be able to see we haven’t left the old one?

In recent weeks, OpenAI has finally completed the convoluted process of restructuring from a non-profit into a more standard for-profit company. Altman doesn’t appear to have a major stake in this new entity either.

Superintelligence is not the only futuristic project Altman is dedicated too. He has also funded ambitious projects in nuclear fusion, life extension, and a cryptocurrency-based universal identity system.

I was recently listening to the rest is history episode on Christopher Columbus. They were comparing him to Musk which I think is really very apt. Altman has a sly human-intelligence that is unlike Columbus who wasn’t good with people in general.

A beautiful and informative essay...thanks for sharing. The only thing I'd add is that Sam, paradoxically, has a kind of humility. Despite being a trickster and a flawed human, he remains intellectually curious about the meaning and significance of AI. A lot of people miss that aspect. The ability to hold uncertainty is part of his gift...and helps him to bear the burden of being a pioneer. I didn't know he was into Advaita Vedanta, but it makes sense.