MIT Study: Using ChatGPT Won't Make You Dumb (Unless You Do It Wrong)

A nuanced AI study, you've got to love it!

MIT has published a study on how using large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT affects your brain and your cognitive capacity. It’s 200 pages—I’ve read it, so you don’t have to.

The findings are relevant and surprisingly nuanced. The authors’ criticism of LLMs—because this is a paper criticizing the abuse of LLMs in educational settings—is supported and qualified by the findings—there’s no black or white here.

The most salient aspect of the study is that it uses a brain monitoring method (electroencephalography, EEG) that directly measures brain activity. This is critical because it doesn’t depend on behavioral data or self-report (what people say they think or feel), which generally suffers from dubious validity.

This is your brain telling you what happens when you abuse ChatGPT.

I. Experimental design: essay writing

To give you a mental image of the study, let me start with the experimental design.

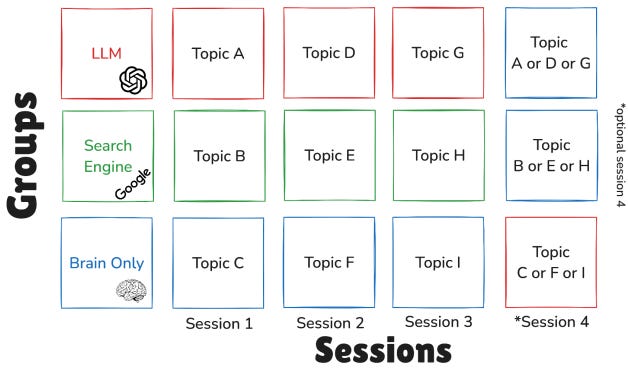

The authors gathered 54 people and put them into three groups: LLM group, search engine group (I will leave them aside), and brain group. Each participant was allowed to use the materials assigned to their group, meaning the brain group had no access to anything except their knowledge and skills.

The study was spaced into four sessions of 20 minutes each over the course of four months. In the first three sessions, each participant had to write an essay from a prompt like this (from the SATs):

Many people believe that loyalty whether to an individual, an organization, or a nation means unconditional and unquestioning support no matter what. To these people, the withdrawal of support is by definition a betrayal of loyalty. But doesn't true loyalty sometimes require us to be critical of those we are loyal to? If we see that they are doing something that we believe is wrong, doesn't true loyalty require us to speak up, even if we must be critical?

In the optional fourth session—the most important—the authors swapped the LLM and brain groups: those who had used an LLM to write during the three previous sessions now had to use only their brain, and vice versa, those who used just the brain now had to use an LLM. 18 people came back for session four and were instructed to take a topic they had familiarized themselves with in any of the previous sessions. These groups are called, respectively, LLM-to-brain and Brain-to-LLM.

Here’s a visual diagram of the study:

II. Five limitations for future research

Before I analyze the findings, here are five limitations of this study (the authors acknowledge there’s more work to be done on these aspects):

The sample is small, meaning the study may lack the statistical power needed to reliably detect small or moderate effects; a much larger sample would be required for that. The sample is also homogeneous: people in the vicinity of MIT surely don’t reflect the distribution of people around the globe: they’re all higher education, high socioeconomic status, Americans, young-ish people, etc.

They used ChatGPT with GPT-4o. They mention you should not extrapolate the results to other LLMs, but I think they’re being overly cautious. I don’t think there’s any reason why this wouldn’t apply to any other LLM (including reasoning models like o3). In any case, more research in this direction would be welcome.

They focused on a writing task for an educational setting. These results may not apply to work activities or real-life settings and may not hold across tasks (writing an essay is highly specific). They also didn’t divide “writing an essay” into subtasks to analyze whether LLMs hinder performance in a subset of them and help in a different subset.

They used EEG, which allows them to measure brain activity, but this method has a low spatial resolution, meaning it’s hard to pinpoint exactly where things are happening. The temporal resolution is high because the bioelectrical signals travel fast. A study that used a more powerful neuroimaging method, like fMRI, with great spatial resolution (worse temporal resolution), could provide key insights.

Cross-sectional study: The authors observed three groups in four sessions, but didn’t conduct a longer follow-up to assess the long-term impact. A longitudinal study (measured over long periods) would provide adequate information as to whether the effect of using LLMs is temporary or permanent.

III. Linguistic and EEG analysis: LLM-only group

The authors divided their analysis into the natural language processing part (I will call it linguistic analysis for simplicity) and the EEG part. Although the EEG is arguably more revealing, I found the linguistic analysis rather insightful, so I will share both. Here’s what they found about the LLM group. Brain group in the next section.

Linguistic analysis

In sessions 1-3, participants got progressively better at writing varied prompts but eventually (session 3) approached the task in a “low effort copy-paste” manner, resulting in essays one could label as “ChatGPT-type essays.” Participants didn’t bother to distance their essays from what ChatGPT would write by default. (Side note: it’s hard to discern how much the variance between sessions 1, 2, and 3 responds to an LLM-induced reduction of cognitive engagement vs tiredness.)

Low perceived ownership and low ability to quote the essay: ChatGPT co-wrote the essay, which made participants feel detached. This is a good thing. The alternative is to feel as yours something that is not. Their inability to quote something that had their name attached to it is, in contrast, a bad thing. This implies shallow memory and semantic content encoding, which translates to “you don’t remember or understand what you co-wrote.”

Human judges noticed little distance between essays across participants (they didn’t know who wrote them a priori). This means, as expected, that people using ChatGPT were writing pretty much the same stuff in terms of structure and approach. This is in line with the widespread idea that LLMs take you to the center of the distribution of words but also of meaning, style, structure, etc.

Longer essays: The LLM group writing longer essays is trivial because LLMs are much faster than humans at writing, are overly verbose by default, and never tire. 20 minutes for them to write something about loyalty or art is an eternity for us. (Humans still had to do the integration, but compilation is easier than creation.)

EEG analysis

Participants showed a decreased cognitive engagement over time due to a familiar setup, meaning “you waste no mental resources if you don’t need to,” which makes using AI appealing from a “cognitive budget” standpoint.

However, there are consequences to this: The authors found ~50% reduced connectivity patterns (which parts of the brain you’re using) and also reduced neural activation overall (how much you’re using them) compared to the brain group. This means that the LLM group engaged their brains less in general. The authors call this an “Automated, scaffolded cognitive mode.”

In session 2, there’s a spike of “integration flow” activity, meaning that LLM users (also search engine users) engage in the activity of integrating large amounts of information that’s been handed to them. Like asking an intern to organize a bunch of papers without having to find and curate them previously or understand them afterward.

There’s a critical detail with the time limits of the experiment that I want to mention here as an aside.

Having 20 minutes to write an essay implicitly pushes participants in the LLM group to focus on copy and paste instead of incorporating their thoughts and challenging ChatGPT. One could think that, given more time, people wouldn't use LLMs mindlessly. However, I hypothesize that this experimental design mimics well the natural constraints of real life. 20 min is a good proxy for: “The deadline is tomorrow,” or “I have to do the laundry,” or “I'd rather be playing videogames.”

This “automated, scaffolded cognitive mode” is how people naturally use ChatGPT when they’re constrained by the duties and responsibilities of real life. ChatGPT acts, first and foremost, as a cognitive unloader.

IV. Linguistic and EEG analysis: Brain-only group

Linguistic analysis

The essays of the brain group were shorter overall (naturally) and also more diverse. This holds across sessions 1, 2, and 3. The perceived ownership and ability to quote remain high across the study for this group.

This means that participants who use their brains take inspiration from their knowledge, their opinions, their experiences, and their identity in a way that people using LLMs don’t (at least under critical time constraints). The brain is also available to this latter group, but ChatGPT acting as a cognitive unloader prevents them from tapping into the rich source that is their lives, and they instead tap into the homogeneous and soulless source that is a compressed internet.

EEG analysis

The brain shows constant high neural activity (intensity of the engagement) and connectivity patterns (scope of the engagement). The brain remains “involved in semantic integration, creative ideation, and executive self-monitoring.” And they add: “The Brain-only group leveraged broad, distributed neural networks for internally generated content.” If you only have the brain at your disposal, you have to do the hard work yourself. You keep your native tools sharp.

V. Session 4: LLM-to-brain and Brain-to-LLM

18 participants took part in the fourth session. This part is the most relevant for those of you who want to approach AI practically and usefully, but still not hinder your cognitive capacity.

Remember: LLM-to-brain are people who used LLMs during the first three sessions and now should use only the brain. Brain-to-LLM, the other way around. They were instructed to write an essay about a topic they were already familiar with from the previous sessions (this is key to remove confounders).

LLM-to-brain

They “Used N-grams from previous LLM sessions.” This means that having used LLMs before engaging the brain biases your vocabulary and expressions to resemble that of an LLM. This is terrible news for people using ChatGPT to learn to write. In a way, they’re becoming stochastic parrots of a stochastic parrot.

Surprising finding here: They “Scored higher by human teachers within the group.” Within the group means that these people, who came from using LLMs for an hour, scored better in the eyes of the teachers than those who used their brains alone in the previous three sessions. This is critical for the education system. It means that a non-professional writer’s brain may not be the best writing tool for them, so they’re incentivized to use ChatGPT. This increases their reliance on an external tool, getting substantial gains in the short term (higher grades) at the expense of a long-term cognitive deterioration (lower mental skill).

The authors put it like this: “Original LLM participants might have gained in the initial skill acquisition using LLM for a task, but it did not substitute for the deeper neural integration, which can be observed for the original Brain-only group. Educational interventions should consider combining AI tool assistance with tools-free learning phases to optimize both immediate skill transfer and long-term neural development.”

Brain-to-LLM

This is huge: “Better integration of content compared to previous Brain sessions. . . . More information seeking prompts. Scored mostly above average across all groups.” It means that using ChatGPT after having written an essay and having engaged with it—participants didn’t know what session four was about, so their engagement in the previous three sessions was serious and honest—is better than just using your brain. Integration is better, prompts are better (engagement with the task > having previous LLM experience), and quality is better. (Note that this applies to non-professional writers, who would benefit much less, if anything, from using ChatGPT at all.)

AI isn’t harmful but helpful if you engage your brain often enough and hard enough: “AI-supported re-engagement invoked high levels of cognitive integration, memory reactivation, and top-down control. By contrast, repeated LLM usage across Sessions 1, 2, 3 for the original LLM group reflected reduced connectivity over time. These results emphasize the dynamic interplay between cognitive scaffolding and neural engagement in AI-supported learning contexts.”

In a way, these findings reinforce my thesis of the golden rule of AI use: “AI is a tool, and like any other, it should follow the golden rule: All tools must enhance, never erode, your most important one—your mind. Be curious about AI, but also examine how it shapes your habits and your thinking patterns. Stick to that rule and you'll have nothing to fear.” Saying “AI is bad” is simply wrong. Context, scope, personal effort, etc., matter when assessing the value of using AI tools.

VI. General conclusions

As I said, this study is not black or white (whatever influencers say). There are many interesting findings, including how using LLM alone is harmful, how using your brain is good, and how combining them in the right order and to the right extent can be a great choice. Some additional general conclusions here selected from the paper:

Brain-to-LLM >>> LLM-to-Brain: “Brain-to-LLM participants showed higher neural connectivity than LLM Group's sessions 1, 2, 3 This suggests that rewriting an essay using AI tools (after prior AI-free writing) engaged more extensive brain network interactions. In contrast, the LLM-to-Brain group, being exposed to LLM use prior, demonstrated less coordinated neural effort in most bands, as well as bias in LLM specific vocabulary.”

Using AI alters brain engagement not just task performance: “Collectively, these findings support the view that external support tools restructure not only task performance but also the underlying cognitive architecture. The Brain-only group leveraged broad, distributed neural networks for internally generated content; . . . and the LLM group optimized for procedural integration of AI-generated suggestions.”

If you rely heavily on AI, you’ll get dumber: “AI tools, while valuable for supporting performance, may unintentionally hinder deep cognitive processing, retention, and authentic engagement with written material. If users rely heavily on AI tools, they may achieve superficial fluency but fail to internalize the knowledge or feel a sense of ownership over it.”

There might be an optimal sequence of tool use: “From an educational standpoint, these results [session 4] suggest that strategic timing of AI tool introduction following initial self-driven effort may enhance engagement and neural integration. The corresponding EEG markers indicate this may be a more neurocognitively optimal sequence than consistent AI tool usage from the outset.”

You should avoid incurring cognitive debt: (Preliminary conclusion, more research needed.) “When individuals fail to critically engage with a subject, their writing might become biased and superficial. This pattern reflects the accumulation of cognitive debt, a condition in which repeated reliance on external systems like LLMs replaces the effortful cognitive processes required for independent thinking. Cognitive debt defers mental effort in the short term but results in long-term costs, such as diminished critical inquiry, increased vulnerability to manipulation, decreased creativity.”

That’s all! This was super fun. I hope you found it useful. I surely did find it useful writing it (I didn’t use ChatGPT to unload the cognitive burden).

I'll keep an eye out for any studies like this I come across, especially if they include neuroimaging methods (fMRI) or if they are longitudinal (we'll have to wait for this).

If you liked this post, don’t hesitate to subscribe using the offer below.

GENTLE REMINDER: The current Three-Year Birthday Offer gets you a yearly subscription at 20% off forever, and runs from May 30th to July 1st. Lock in your annual subscription now for $80/year. Starting July 1st, The Algorithmic Bridge will move to $120/year. Existing paid subs, including those of you who redeem this offer, will retain their rates indefinitely. If you’ve been thinking about upgrading, now is the time.

Here's what I'm thinking. This is a brilliant paper. It demonstrates the asymmetrical effects of AI. And as you have aptly put it, the social media influencers may be jumping at attention-grabbing words only because that is how they achieve online engagement.

But as you have mentioned, that there is an optimal situation for using AI, I don't think it can become feasible for us to continually use it optimally. I'm reminded of Kahneman's book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, where the author confesses that his deep understanding of biases does not stop him from falling victim to them.

Our brains were not wired to reason, but to budget. If AI allows us to reduce the budgetary costs, we will take that option. Few people hope to improve their cognitive power. Heck, a good number of your subscribers do. But that may be a small tail in the distribution. As Gurwinder has previously mentioned in his correspondence with Freya India, the smart will acceleratingly get smarter, although I prefer to use the word high-agency individuals. Same for the low agency guys. That split may continue to widen.

"stochastic parrots of a stochastic parrot" - love it!