How to Want Things Again

We all live in a perpetual state of unwanting

Sam Kriss wrote a fantastic essay on streaming platforms and zombies. Don't ask me how he managed to combine those topics, and go read it. It's… special. His basic thesis is powerful: We no longer consume algorithmically-sorted content, we consume the sorting algorithm itself.

At first I thought, “What the hell is he talking about,” and then I thought, “yeah, he’s definitely right.” I found the simplest example that verifies Kriss’s hypothesis: We don't say, “What are you watching on TikTok?” We use the verb scrolling. Why? Because the watching part is not relevant. The video itself is only interesting insofar as it belongs in the middle of an infinite chain of videos. Your brain doesn’t yearn for you to consume content but for you to scroll past content.

The real reason why you waste your life on social media is that your brain wants to consume the liminal space—the transition—between content. The highest high is not at the beginning of a video, not even at the end—when have you last watched an entire 60-second clip?—but at the moment your finger taps the screen, the current video is already halfway gone, slipping off the top edge, while the next one creeps up from below. It is at that fleeting instant, barely noticeable, that you see the infinite chain: the physical boundary that connects one video and the next.

The chain is what your brain feeds on. Haven’t you noticed that whatever you're watching at any given moment in an algorithmic feed is the least interesting thing ever? Think about it: When it begins, your brain immediately begs you to scroll. It wants the high from randomized rewards; will the next video be good or not? But it doesn't want to know the answer, just a reason to ask the question.

Don’t get me wrong, I say TikTok, but the entire digital culture is like this. Kriss, for instance, focuses on Twitch and streaming services, but it’s everywhere. The “current thing”—whatever is driving the cultural conversation for the chronically online at any given moment—plays the role of placeholder for the feeling of the existence of a “next thing.” It’s not the freshness of a current thing but the promise of a next thing that we so eagerly seek. Yes, we are that sick.

This week’s meme, gracefully and accurately capturing the zeitgeist for the extremely long period that is 72 hours, is only interesting insofar as it's the one that precedes the next meme in the infinite chain that is the meme cycle.

This is also why AI video content works so damn well and why I believe it is the ultimate form of social media platforms: endless chains of AI slop.

Unlike human-made TikTok videos that scream, “hey, care about me, I'm also important,” AI slop doesn't try to convince you; it’s just there, sufficiently satisfied with its role as space-occupier in the infinite chain. It’s pure placeholder essence, pure liminality, pure in-betweeness. AI slop’s ridiculously huge success entails the subconscious acceptance that, in a world of digital abundance and perpetual change, things only matter insofar as they embody prior-ness. No pretense of self whatsoever. No pretense of meaning. No pretense that watching matters, only scrolling.

AI slop videos are the perfect appetizer for a generation of zombies that, having been conditioned by the sorting algorithm, have ended up like Pavlov's dog, salivating at the ring of the bell.

Ok, that was the preamble.

My question today, a question I want to desperately answer for myself because, like Kriss, and like every single one of you, I’m in “my zombie era,” is how the hell do I overcome the drastic deterioration of my brain? How do I stop myself from turning into Pavlov’s dog, eating bells for breakfast? How do I stop my brain from seeking the sorting algorithm? How do I reverse-zombify myself into a human again?

Which, to use a more practical lens, is another way of saying: How do I want things again? I will give you 3 ideas I have personally used with much success.

I. Hack your brain back

Unfortunately, the brain is extremely adept at avoiding being hacked out of the things that give it pleasure. You got brain-rotted by the sorting algorithm? Good luck unrotting it. But it's possible. The brain is better at only one other thing than resisting giving up an addiction: getting addicted to a new thing.

Indeed, you will notice how thematically appropriate this is: the brain rots by feeding on content whose sole purpose is to give way to more content in an infinite chain—and it's only capable of escaping that vicious cycle by entering a new one.

However!—and this is the only reason why this can work as a solution instead of aggravating the issue—it becomes vulnerable to your conscious hijacking while it's busing giving up one vice for another (for nerds, it's like hacking a computer while it's doing an OS update). It is in the liminal space between videos that we get hooked on TikTok, but it’s also in the liminal space between vices that habit can blossom.

This requires careful planning. You have to find something else your brain can get hooked on that is actually good for you. (People take up vaping when quitting smoking, which can be even more harmful—don’t do that, kids.) Reading? Taking walks? Exercising? Hanging out? Sex? Singing? Knitting? You just have to choose.

Then comes the hard part. How do you actually, in daily practice, transform your behavior? What has worked best for me is to simply take awareness every time (or as often as you can) you indulge in your vice and say out loud: “Wait, let’s do this other thing I want to want to do.” And then you throw away the phone and pick up a book. It doesn’t matter if you read more than a couple of pages. The goal is to teach your unconscious brain to think of books when picking up the phone.

At some point, you will notice that your brain is switching gears; it no longer asks you for vice 1 but for vice 2. By then, the tight yoke vice 1 had over your mind is pretty much broken. You’re free to direct your volition toward vice 2. Except vice 2 is a virtuous habit in disguise. Your conscious brain would never fall for it, but your unconscious brain—which is in charge of your wants—is dumb.

This is a vegetable-dressed-as-candy type of trick that even a 3-year-old could detect. That’s why it needs to be a self-deal. You tricking yourself is the only way this works. In case you feel bad, remember that your unconscious brain tricked you into scrolling TikTok or whatever all day; the least you can do is repay in kind.

In my experience, this is the safest and most replicable way to hack a way into your wants, which are otherwise beyond your control. I did this when I was addicted to playing video games in college. A few months later, I was spending my mornings fixated on solving differential equations for my calculus II exams. It felt genuinely thrilling. By making the jump between vices conscious, I opened an opportunity for virtue. Willpower became substitution, which became interception. A life-changing trick.

And remember: opportunity for change only arises in the interaction with the problem itself. Ruminating about how bad you did today while trying to sleep at night won’t get you an inch closer to your goal. Accept defeat and prepare to try again tomorrow.

II. Nurture your will

This is the brute force equivalent to the above. You can will yourself into things.

(This is the powerful meta-version of “you can just do things.” While “doing things” operates at the conscious level of action, “willing to do things” operates at the unconscious level of wants, which is inaccessible through normal means, and so it requires special treatment.)

Likewise, you can will yourself out of things. In rare cases, both things are the same thing: You can wake up one day and will yourself out of your zombifying conditioning and into whatever craft you've wanted to try all your life but have always found excuses to not even start. Reading, taking walks, exercising, and blah blah blah. The hard part is not having a “to-do” list that’s actually a “will never do” list, but making it into an “I will do” list. Will and will are not the same word by accident. You will do X because you will will yourself into doing X.

Now, transforming “will” (determination) into “want” (desire) requires an almost mystical mindset change, and I cannot help you with that. But I can summon two big names in the literature canon to do it for me: Scott Alexander and William Blake.

Alexander argued, earlier this year, that the framing of the semantic apocalypse—nothing has meaning anymore because we have too much of everything—only makes sense socially but not individually. “Where is your agency?!” he asks, dumbfounded by how deeply people get swept by the feeling that they can’t move the entire world at once without realizing they can move it, grain of sand by grain of sand.

Paraphrasing G. K. Chesterton, Alexander writes, “If you were really holy and paying attention, then the thousandth sunset would be just as beautiful as the first.” Which is another way of saying: will yourself into seeing the sunset just as beautiful every time, and you won’t want to pick up the phone last thing at night ever again.

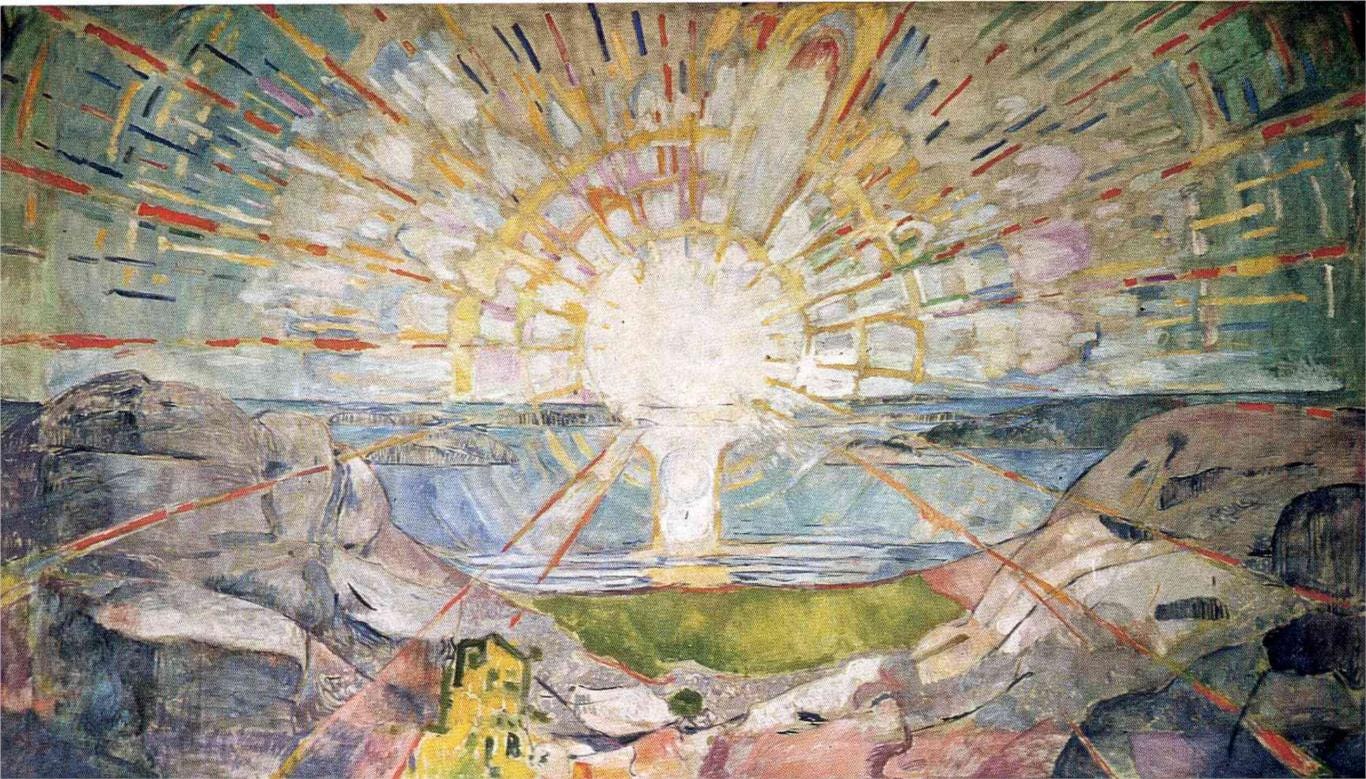

Alexander then quotes William Blake, who wrote about the sunrise in 1810, as part of the analysis of his painting A Vision of the Last Judgement:

I assert for myself that I do not behold the outward creation, and that to me it is hindrance and not action. "What!" it will be questioned, "when the sun rises, do you not see a round disc of fire somewhat like a guinea?" Oh! no, no! I see an innumerable company of the heavenly host, crying, "Holy, holy, holy is the Lord God Almighty!" I question not my corporeal eye any more than I would question a window concerning a sight. I look through it and not with it.

You can wake up tomorrow morning and choose to transcend your senses; give up the “objectively true” nature of the sun as a “disc of fire” that looks like a coin and will yourself into seeing it as this otherworldly, marvelous, easily deified creature flying impassively in and out of the horizon, as it caresses the skin of its Moon partner, in an asynchronous but rhythmic dance of flames and shadows; while giving away light, heat, and life asking for nothing in return but not tolerating any approximation of the flesh (which makes it quite convenient that God chose to keep it exactly the right distance from us); as it cooks helium in its own belly by fusing a countless number of primigean hydrogen atoms in a photon-emitting process that, just by itself, justifies our awe when witnessing the sky in a cloudess night. Then do it again the morning after tomorrow. And forevermore until your last morning.

Anything is as beautiful or as ugly as the beholder is. Alexander, Chesterton, and Blake write about the sun rising and setting because it is the quintessential “undeservedly taken for granted” object. But you can will yourself into experiencing anything—the tiniest, most unimportant object, like a grain of sand, or the most ephemeral, inconsequential event, like the flapping wings of a butterfly—as big and beautiful as an entire universe. If, conversely, your universe is as big as your phone, how on Earth would you want to exist anywhere else?

Here’s a more pop-neuroscience interpretation of why this happens: when you align your perception, your attention, and your awareness into a single point in space or event in time, you're effectively letting it occupy your whole present. Do it often enough and you will regain control of your mental powers, and thus your ability to want a life worth living.

Willing yourself to experience life as deeply and presently as your status as a human being allows you to is the ultimate self-gift.

III. Frightening inaction

The last advice is not about doing something new from an old vice (1) or about doing something old in a new way (2)—both moved by what can only be described as hopeful action—but about not doing something old anymore. Number three is about frightening inaction, an equally powerful method as 1) and 2), but of opposite valence.

Behavioral psychology 101—although we could will ourselves to appreciate Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s contribution, which at some point was novel and insightful, instead of taking it for granted—says that you are more scared to lose $100 than you are happy to find $100. This cognitive bias is called loss aversion. If, instead of framing what you could gain if you did things differently, I show you what you're losing by staying a zombie, your loss aversion will push you out of your numbness. This is what you do when everything else has failed.

I've done this with myself many times with incredible success, but one of those times is especially memorable. Let me tell you a story which is, in a profound way, the story of my life.

Twelve or so years ago, I was lying on my bed after college, ruminating. It was literally just another day, equally dreadful and ugly as the thousands of others that had come before (remember, the thousandth time deserves as much unwavering presence as the first—thank you, Chesterton). But that day was actually different.

To put you in context: I was a twenty-year-old boy riddled with debilitating anxiety. I could barely do any social activities that were normal at my age. I didn't know what to do about it, but I was decent at thinking things through (you know, “master of introspection; deficit in execution”). So that day, crying in bed, I projected myself into the distant future.

“What will my life look like 10 years from now?” I silently asked. My mind displayed a haunting picture. I forced myself to make it vivid—if I wanted the exercise to have any lasting effect, I had to be genuinely afraid of the perpetual mistakes I was incurring. Here’s what I saw in a list format that falls short of conveying the level of panic I felt: No girlfriend, no children, no job, no home, no friends, no ambition, no self-love—a 30-year-old man, forever free to be a prisoner of his own inadequacy. I vaguely recall having whispered out loud, “Either I get out of this, or my life is already over.”

With the benefit of hindsight, I can say that was the most significant inflection point in my life—nothing else comes close. Probably, nothing else will ever come close. I manufactured an existential form of loss aversion. I was so unbearably afraid of not having a life that any other fear paled in comparison.

For the following 5-6 years, I kept a vivid memory of that feeling. I painstakingly fought my fears day after day, actively seeking out opportunities to face them. I felt awful, many times on the verge of backing down and surrendering, but when my strength was most faltering, I repeated: You know why you're doing this. That sentence was enough. It was always enough, whatever monster in the shape of a social interaction awaited me.

So, knowing my story, you know why I'm in a position to ask you: Are you sufficiently afraid of not having the life you want? If you died right now, would you be happy with the life you've had so far? Have you pursued all the things you wanted to the extent you wanted? Did you witness the sun with as much passion today as the day you saw it for the first time? Or have you spent your last forever mornings doomscrolling yourself through the empty spaces of some digital platform?

If I tell you, “You could have everything you want,” you may not move an inch. Not having what you want is not powerful enough. Some cases require an existential form of loss aversion. As Fyodor Dostoevsky advised us in Crime and Punishment: Don’t betray yourself for nothing. Be unapologetically afraid of what you are losing by being a zombie, and you will experience an instant metamorphosis into the beautiful human being that you once were.

I think you're leaving out the role of community / belonging in fighting the condition you assess and name. If, indeed, you believe it is a problem.

Having a tribe is a huge predictor for success and emotional resilience.

Loneliness, the opposite.

You and Sam Kriss are apparently using tiktok in a very different way than me lol. If im interested in a video or creator, i watch it to the end whether its 60 seconds or 5 minutes (sometimes on 2x speed). If i really wanna engage with it, i go to the comments section, and often leave a comment. Im def interested in the content im consuming, and if its engaging enough, i leave the app to go down a rabbit hole or think about what i saw. Im def not there to just "consume the sorting algorithm," im there to do the same i thing i did on twitter back when that was the meta: be one of the cool kids that are in the know about trending topics. And based on the activity i see in every comments section, so are a lot of other people