Claude Code Coded Claude Cowork

The beginning of recursive self-improving AI, or something to that effect

I. Is Anthropic winning the race?

After three years of paying OpenAI for ChatGPT Plus and a few months of paying Google for Gemini Pro, I’ve decided that Anthropic is winning right now and have allocated my entire budget for AI tools on Claude. That said, you might be surprised to learn that I don’t use Claude Code.

Claude Code is currently the flagship product of the company. I don’t want to take away from the insider-targeted victories of Sonnet 3.5 in June 2024, and Opus 4.5 in November 2025, but Anthropic is clearly the best AI startup at selling to enterprises and convincing their developers to choose Claude. Claude Code is the reason a growing number of insiders think that Anthropic might end up being stronger than OpenAI (Google is a different beast altogether). I am neither an insider nor a developer, but I, too, think Anthropic > OpenAI right now and Claude > ChatGPT.

As a Claude user who doesn’t use Claude Code, I felt I was missing out; had I chosen wrong in pursuing a literary, writerly life instead of leveraging my technical past as an aerospace engineer? In my anxiety, I began to wonder when Anthropic would launch a Claude Code for non-coders. I guess Anthropic was thinking that, too, because yesterday they announced Cowork, explicitly marketed as “Claude Code for the rest of your work.” When the race ends, I will swear I was an Anthropic fan since the very beginning. (Demis, I still trust you!)

Anyway, Claude Code, for those of you who are, like me, non-technical, was launched as a product in late 2024; it’s a command-line (CLI) tool that lets developers delegate coding tasks to Claude directly from the terminal. Basically, Claude Code is your periodical reminder that the best AI tools are guarded behind hacker-like interfaces that most non-coders have only ever seen in movies.

Despite having an uphill battle against OpenAI and particularly against ChatGPT’s immense popularity and generalist nature (it’s quite intuitive), Claude Code quickly became one of Anthropic’s most successful products. To my surprise—and apparently Anthropic’s staff—developers found Claude Code to be so good that they started to take it beyond its intended scope: vacation research, email cleanup, knitting (?), subscription cancellations, photo recovery, taking care of plants (?), and many other interesting use cases that Anthropic highlighted in this thread. People were “forcing” a coding tool to do non-coding work because, as Boris Cherny (Claude Code’s creator) notes, “the underlying Claude Agent is the best agent, and Opus 4.5 is the best model.” Given my latest AI tool purchasing choices, I will have to agree.

Anthropic’s Cowork will now fill that niche. It is, in essence, Claude Code with a UI; Anthropic made its magic widely accessible (some think it might be perhaps too powerful for muggles). You give Claude access to a folder on your computer, describe a task, and it plans, executes, and loops you in on progress. No terminal required and thus no technical knowledge.

However, I’m not here to review Claude Cowork or explain what it improves from Claude Code (in a broadly positive review, developer Simon Willison says “not a lot”) or Claude Desktop, or other agents. I also won’t explore what is still missing for non-coders (it’s a research preview rather than a finished product, so keep that in mind). There’s plenty of that content already in news outlets and other blogs, and on Twitter—and I’m not even sure I need Cowork for anything myself as a writer who only needs one document at a time to make my own magic!

So I’m writing this for a different reason. Cowork might be marketed as “Claude Code for the rest of your work,” but it is also the beginning of the rest of our lives.

II. Claude Code coded Claude Cowork

Nice headline, huh? Here’s the detail that elevates this from a product announcement for AI geeks to something worth paying attention to, well, philosophy geeks: according to Cherny, all of Cowork’s code was written by Claude Code. According to Anthropic engineer Felix Rieseberg, it was built in about a week and a half over the holidays. So, an AI tool coded another AI tool, ready to be shipped in 10 days. It is a prototype, yes, but this is incredible for at least three reasons.

First, although AI writing code is far from new and far from an isolated phenomenon (30% of Microsoft’s code and 25% of Google’s code is now AI-written; all of Cherny’s contributions to Claude Code in December 2025 were themselves written by Claude Code + Opus 4.5!), the detail is not “AI writes code” but that Cherny’s tweet was “All of it.” No one doubts at this point that AI is used internally to code stuff—“dogfooding” is good when you want to know what users feel; it’s great when you do it because your product is simply the best there is—but, all of it?

Second, in March 2025, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei told a Council on Foreign Relations audience: “I think we will be there in three to six months, where AI is writing 90% of the code. And then, in 12 months, we may be in a world where AI is writing essentially all the code.” Others have made similar predictions, but Amodei was the boldest (and has consistently been). By September 2025, commentators marked the six-month anniversary of Amodei’s prediction and declared it a miss. In a different article where I quoted his prediction, I called it “far-fetched.”

My question is: in the grand scheme of things, will it matter that he was “wrong” by 100 or so days? I don’t know what’s more impressive: that Anthropic is doing its best to fulfill its chief executive’s prophecy or that Amodei was right in a sort of “inevitable future” kind of way.

Third, the recursive element. Claude Code didn’t write a minor feature but a tool that extends its own paradigm to a bigger market. There’s a lot of money to be made from a Claude Code for non-coders tool that works a well as Claude Code does. For years, debates about AI risk and alignment have circled around the idea of recursively self-improving systems—AI that can improve its own capabilities, creating a feedback loop that accelerates development in ways that become difficult to predict or control—but those debates were theoretical, focused on hypothetical future systems.

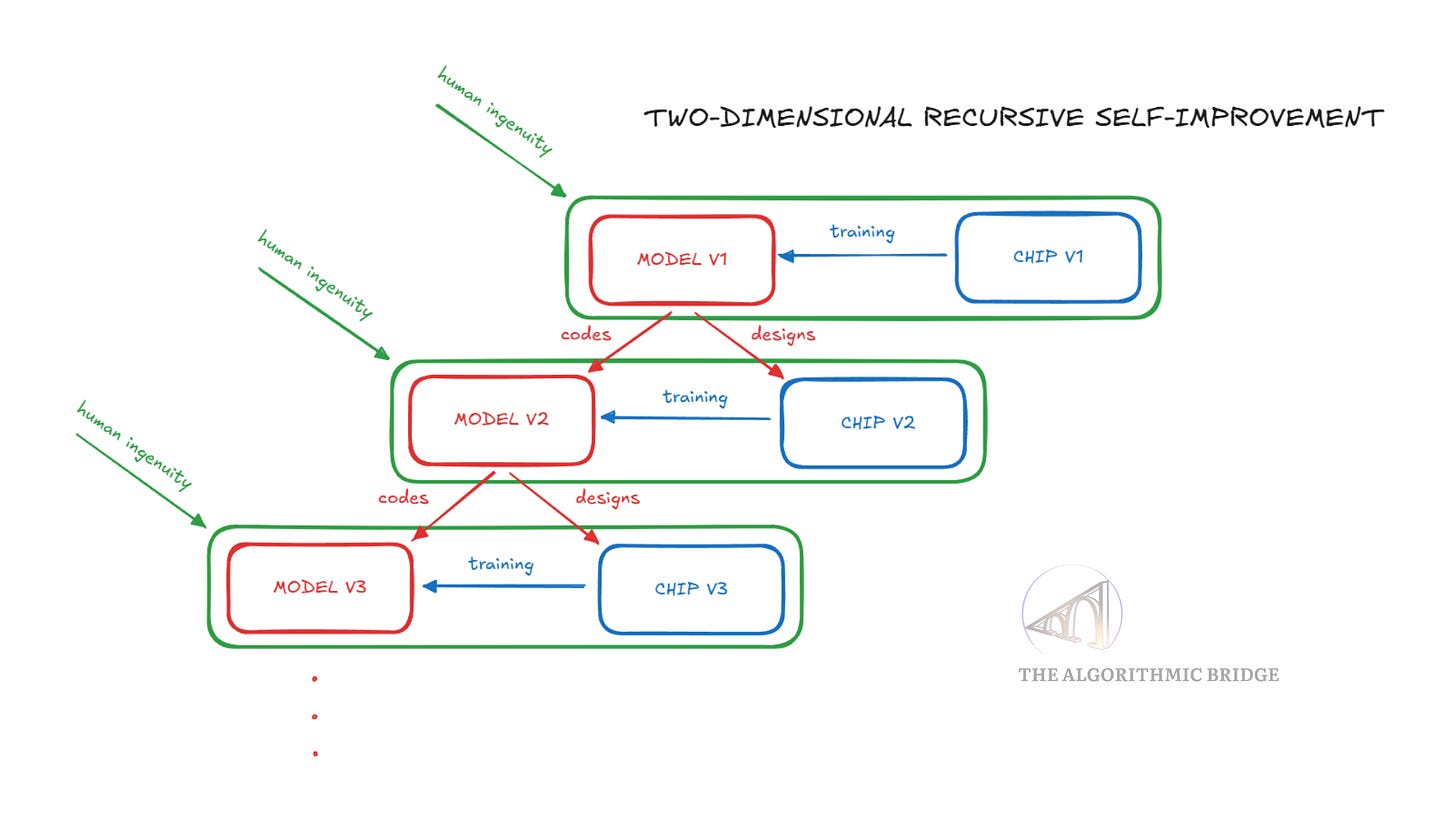

In *AI Is Learning to Reason. Humans May Be Holding It Back,* I wrote that AI “wants” to be better than us and will be once we let it grow beyond the limitations we impose on it without noticing (AlphaZero, DeepSeek-R1 Zero are examples of better-than-human AI systems that didn’t need human knowledge or instruction). Soon after, Google published details on AlphaEvolve, a tool that is improving other parts of Google’s software and hardware infrastructure: “[it] pairs the creative problem-solving capabilities of our Gemini models with automated evaluators that verify answers, and uses an evolutionary framework to improve upon the most promising ideas.” I made the figure below to illustrate what’s going on with the recursive self-improving AIs (think about an AI that codes better AI models but also designs better chips to train those models):

Cowork is another instance of this pattern, one that Cherny and others have warned about for months now: “Software engineering is changing, and we are entering a new period in coding history.” Cowork might not be improving recursively just yet, but the loop, however modest, is closed. Whether it stays modest is the question.

III. The hidden human in the loop

Hey, hey, hey. Maybe you overused the word “loop” today, Alberto? Ok, before I extrapolate too far and define Cowork as the “beginning of the end” (or perhaps the end of the beginning, if you’re optimistic), it’s worth noting what we don’t know: Is the loop really closed? Is AI writing all the code for entire features, entire products? Maybe, yes, I believe that’s possible. But is it doing all the work that is required for those products to exist? I really don’t think so; I don’t think it can.

In the deep-dive I published yesterday, How AI Will Reshape the World of Work, I argued that AI can’t replace humans when it comes to tacit knowledge, the kind of know-how that you only learn in a sort of master-apprentice relationship, and proposed a hybrid model that combines office and guild dynamics. I stand by that, even if now one can make truthful assertions of this kind: “Claude Code codes Claude Code codes Claude Cowork.” The reason is that we don’t know how much human guidance was involved; not even Anthropic developers might know. I bet they’re quite smart, so this is not a question of intelligence or observation, but a matter of humans’ blind spots.

Here’s a question: In using Claude Code to code Claude Cowork, how much of the work is the prompt, the instructions, the context, the decision-making, the taste, and judgment? How can one factor in the realization that a tool like Cowork will be useful for many people and spark an entirely new market of applications? I don’t claim Cherny or others are saying that a product like Cowork could be entirely AI-created “from zero to one” (that’s a much stronger statement than “AI wrote all the code”), but I find it useful to remember the value of the work humans still do in this new period in coding history. We tend to take it for granted, we tend to forget how hard it is to acquire the skills that allow us to do our work seamlessly, effortlessly, quickly.

What this new paradigm of AI that codes AI that codes AI teaches me is that 1) wow, AI is indeed incredible, and 2) wow, perhaps the “soft,” unmeasurable work humans do is a much bigger piece of the pie than we thought; after all, these tools are far from automating the entire economy (they’re far from even trying to take on that challenge). Isn’t Claude Code a proto-AGI? What else does AGI need, then? AI people forget, way too often, that the “G” in AGI stands for general and that is, by far, the hardest challenge of the AGI goal. Yann LeCun says humans are not general intelligences, Demis Hassabis says LeCun is “incorrect,” and we are, indeed, general intelligences. It doesn’t matter who’s right because the truth is that, however you classify humans, it’s undeniable that we are capable of things AI can’t do—and has not improved much in many years—and vice versa; our shapes of intelligence are simply distinct.

Claude Code building a Claude Code-adjacent product is a home game: the engineers know the tools, the codebase is presumably well-structured and well-documented. Claude may be particularly suited to working on its own infrastructure, who knows? Whether it could produce similar results in an unfamiliar codebase, unfamiliar domain, with unfamiliar engineers, is a different question. Whether it can do things that tacit-trained humans can do is also a different question. The labor distribution matters for interpreting what tools like Claude Code or Cowork tell us about autonomy and the future of the world.

Whatever the case, I applaud Anthropic developers and engineers for being so stubbornly good at what they do. The hidden human remains in the loop, but right now, the loop starts and ends with Anthropic; quite an appropriate state of affairs with that name, don’t you think?

I'm not a betting man. But if I was, I would put my money on Anthropic.

Now I have a more interesting comment 😉: we need to closely monitor what happens in software development, because it’s one of the first areas to be impacted by AI.

It has the highest adoption, some of the best model performance, and very receptive users. So to me, software engineering is a live lab for what will come next to knowledge work