AI Video Should Be Illegal

Are we really going to destroy our trust-based society, just like that?

I.

AI video should be illegal.

Let me start my case with a straightforward example I got from astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson’s YouTube channel:

That is scary.

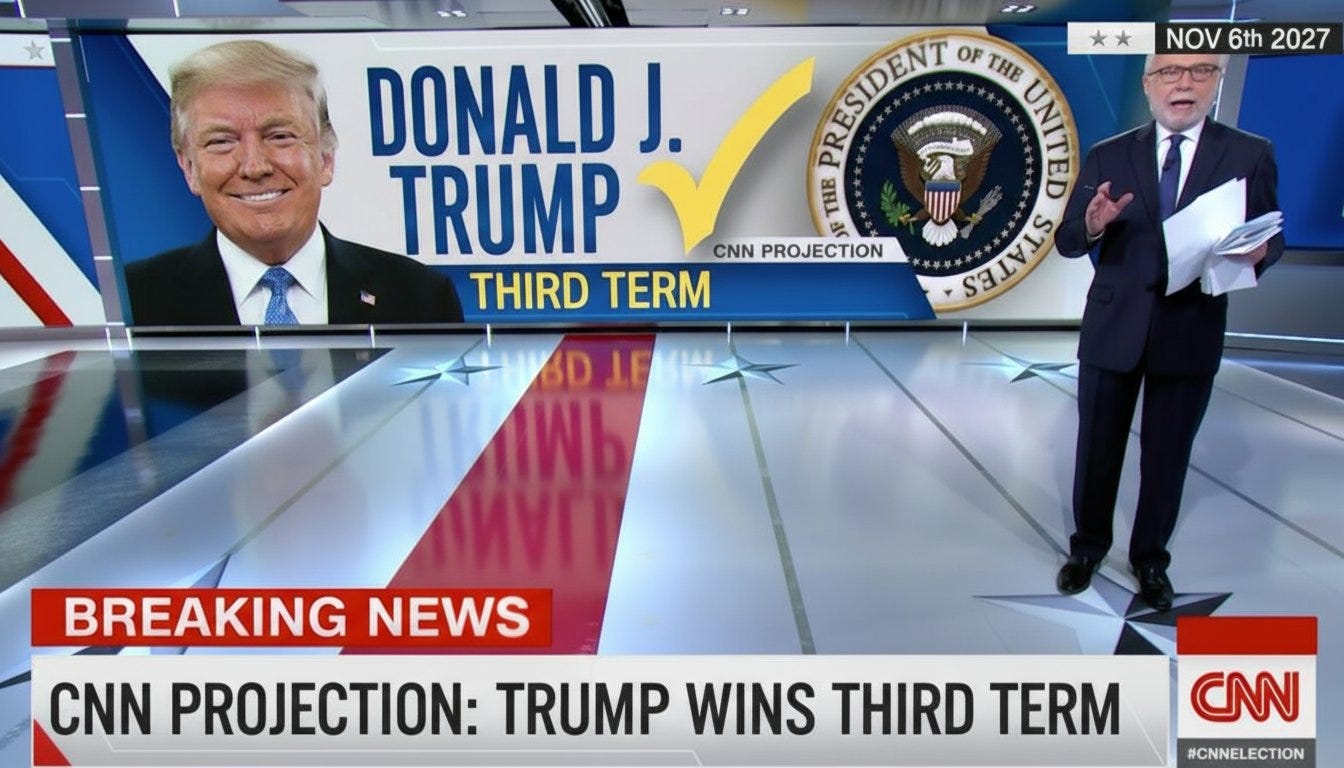

Imagine a deepfake of this quality of Donald Trump saying something barbarous like “We’re gonna do a third term, okay? They don’t want me to, but we’re gonna do it. Everybody’s saying it: Our country is in serious trouble, folks.”

Sounds crazy? Here’s what Nano Banana 2, a new image model by Google, can do:

Within three to six months, you will have the same thing for video.

A “Trump third term” video deepfake doesn’t sound so crazy now, right? I can no longer tell that this image is a fake, just to be clear. I know only because Google has somehow implemented an invisible (and hopefully indelible) watermark (good for them). But the tech is well past the point of obvious telltale cues (where did we leave the crooked fingers and six-finger hands?).

I’ve heard people suggest there’s a reasoning model (Gemini) underlying Nano Banana 2, and that’s why it’s so good. Whatever the case: AI can now make real anything you want to believe and thus anything others want to believe as well.

“Fair, Alberto, but who’s gonna believe a fake ‘Trump 2028’?” I’m glad you asked because I only used this easily debunkable example to grab your attention for those cases you can’t possibly fact-check.

Imagine a deepfake of something more insidious, harder to corroborate, like the report of a terrorist attack in New York City. Or something that spreads faster, like a testimony from the CIA director that aliens exist. Or something that could turn your intimate life upside down, like fake revenge porn of yourself. Or something mundane, barely noticeable, like a spam videocall; except, suddenly, it turns into the worst nightmare possible: “Wait, that’s my daughter? Sweetie… what’s—why are you handcuffed?” “DAD, PLEASE, THEY’VE KIDNAPPED ME. PLEASE!!!”

That is terrifying. AI video (as well as other AI-generated audiovisual media) is a direct attack on a society built on trust over knowledge.

What I mean is this: we know only a bunch of things firsthand, but not many. I know who my neighbors are, where my family lives, and what my cat’s name is. Also, what color are the London plane trees down the street during Autumn (yellowish with red tints but not green anymore), or what time of night do streetlamps turn on in Madrid, or, if I’m being generous with my knowing skills, that gravity does exist (or the apple in my hand wouldn’t fall were I to drop it).

But what else do I know firsthand? Not much! Most of my alleged knowledge is secondhand at best; I trust the testimony of other people to form a model of the world. Did Isaac Newton discover the law of universal gravitation? Yeah, I guess; that’s what my physics books say. Did he have a eureka moment when an apple tree dropped an apple into his head? Hard to believe, but ok; I wasn’t around to ask him.

Don’t confuse, however, my playful tone with the matter being just unserious philosophical epistemics that in no way concern real life. Here’s another one: Who is Spain’s president? Do you know? Do you actually know, know? It’s a simple question but not easily answered: I have to trust the urns, and then the TV stations, and maybe the newspapers (when I read them at all), and all the people who assure me, as if they knew, that his name is Pedro Sánchez and he’s tall and handsome and whatever.

To address this fundamental feature of a complex world—you can only know the bare minimum by yourself—we build trust in curated sources and shared fictions. And then we go on with our lives as if this is an acceptable state of affairs!—Who is Pedro Sánchez? I don’t know!—We convince ourselves that our sources are trustworthy and that they will remain so under any event, like, say, a deepfake epidemic.

And most will, to be sure! But there are also those sources we take for granted as trustworthy without realizing they’re vulnerable to forgery, impersonation, or counterfeiting, such as the president of the United States or a famous astrophysicist.

Many people, including me, have been warning about this subtle change in the dynamics of “knowing” for years. It was a matter of time before what began as badly edited fake pictures of porn actresses with celebrity faces (around 2014, when the term “deepfake” was coined by a pervert) would turn into perfectly believable minute-length high-quality videos (with audio).

Veo 3 from Google DeepMind and Sora 2 from OpenAI, among many other AI models, made it inevitable. Here’s one such warning about Sora from February 2024:

OpenAI Sora is okay but not great. If it was bad, this article would not matter. If it was sublime, it’d be too late. We’re at the critical time window when, like a newborn cat, we must open our eyes or go blind forever. It’s the brief period between the moment we see the storm appearing on the horizon and the moment it hits us with all its power and wrath. . . . Sora 2 will be much more powerful. A kind of improvement we wouldn’t get from linearly improving existing tech. . . .

What makes Sora special . . . is its scope. Sora is not your everyday deepfake maker (hardly accessible except for the most tech-savvy people and constrained in scope), but a boundless reality-twisting tool soon to be in the hands of anyone.

While governments and institutions did little to prevent this, industry leaders like OpenAI and Google raced to get there first and inundate the world in deepfake slop (watermark or not, people will fall for it); people laughed at the six-fingered hands, mocking the obvious mistakes, but most are yet to learn the first law of deep learning: you don’t bet against it. They will cry once those mistakes are nowhere to be found.

In other words, our “critical time window” has closed, and, like a newborn cat forced by circumstance (or by an experimenter’s hand), we’re blind. We will have to learn to live by inverting the dynamics of acquiring knowledge and building trust: we used to trust first and check later, and now we must check first and trust later. If ever.

Or, conversely, we could make AI video illegal.

II.

A tweet by photojournalist Jack Califano inspired this article:

I genuinely think AI video should be illegal. The most obviously societally corroding invention maybe ever created. Just an instant tool of widespread distrust and mass psychosis. . . . At the very least you should be able to sue people into oblivion for using your likeness without permission.

He’s so obviously right that I wonder why this hasn’t yet come to pass. “Societally corroding” is the best succinct description of what AI video is (“soul-draining entertainment” is a close second). When it is for leisure, it’s not better than TikTok. When it’s not for entertainment, the motivations are, almost always, worse. The information ecosystem can only improve by making it illegal.

AI companies don’t actually need Sora 2 or Vibes, or Veo 3 to eventually cure cancer, which they use as an ad-hoc justification. That’s the bullshit they tell investors—we’re not the audience for those kinds of claims; we’d never believe them—to rationalize the immense spending on AI infrastructure and the need for unfathomable amounts of user data. The simple truth is that, if AI video were banned and the ban were enforced somehow (hard to do, I know), the world would be a better place. Despite what a16z’s founder, Marc Andreessen, and the VC class think, it is worth cultivating ethical considerations and “moral discernment” when building or financing innovation.

Would the world really be better, though?

Let’s say AI videos are forbidden. Making, possessing, or distributing a video deepfake is a crime. Now imagine the following scenario (not hard to do, sadly): A powerful politician, let’s call him Mr. Odep, is caught on camera with a minor.

A reporter from a prestigious news outlet gets the leaked media from an anonymous source and says on Twitter that he will publish a video that’s about to turn the political world upside down. Mr. Odep gets a heads-up, picks up the phone, and starts making serious calls with his serious voice to his powerful—and serious—friends. He figures out the journalist’s name and contacts his employer: “That video is a deepfake. If you publish it, your reputation will be destroyed, and someone may end up in jail.”

In parallel, Mr. Odep begins an unofficial, behind-the-scenes prosecution against the journalist, threatening his career and family, all the while Odep’s intelligence squad searches for his dirty laundry (there’s not much, but they can make up for it with some deepfakes).

The journalist believes the video is real; he trusts his eyes and knows Mr. Odep is a genuinely cruel bastard, but his source is anonymous; he can’t be sure 100% now that deepfakes are so good. He has no solid proof, and is risking too much if he goes on a legal fight with this powerful, corrupt, serious politician. The world deserves to know, he thinks, but with the law against him, he admits defeat.

Now imagine that this sets a precedent for all kinds of crimes for which video footage was, until recently, a useful—largely unfalsifiable!—type of evidence. Every single corrupt, powerful person in the world suddenly has a handy scapegoat: all evidence can be accused of being fake evidence and thus shut down by force of law.

So, having banned AI videos, we’re left with a healthier information ecosystem, yes, but also with a political and economic elite shielded from any accountability. Is that worth it? I am not sure. So, maybe, then, we should simply not make AI videos illegal.

Fuck it, we will adapt; we always do!

III.

Now, imagine a parallel world where AI videos have not been made illegal but instead are broadly accessible and generally assumed to be the default (sounds familiar?). What do you think happens to our hero journalist in this case? Does he publish the video? Is he safe? Do we get universal justice against Mr. Odep, also known as Mr. Above-the-law?