The True Power of AI Deepfakes Is Not What You Think

They don’t often fool you, do they?

I. Welcome to Fakesville

When Pikesville woke up the morning of January 17, 2024, they didn’t expect to be on the news. A small suburb northwest of Baltimore, it wasn’t used to attention. By sundown, however, it had become the center of a digital storm. Its name trending for all the wrong reasons.

Eric Eiswert, principal at a mostly-black high school in a mostly-white city, had chosen the wrong day to be white. An audio clip of him allegedly “denigrating Black students,” as The Information later put it, started circulating on social media. The mildest thing the recording said was, “I seriously don’t understand why I have to constantly put up with these dumbasses here every day.”

The situation escalated rapidly when an anonymous Instagram account and one of Eiswert’s former students with a sizeable audience on X shared the audio to more than 1 million followers combined, igniting a viral reaction: “I am in no way surprised by his comments in this recording,” the student said. Then came demands for his removal as principal. Then, the death threats. Police were soon deployed to protect Eiswert and his family at their home.

For days, Eiswert’s life was a nightmare but eventually, investigators figured out what had happened. Eiswert’s audio turned out to be a fake made by one of his rivals at Pikesville High. A team of detectives arrested the perpetrator on April 25.

The audio he made was not just any primitive fake, though, it was a particularly advanced type made with the latest AI technology, a deepfake—if it can fool an entire city, it can fool the entire world.

II. Good deepfakes, bad deepfakes

I've lost count of how many deepfakes I've seen. Good deepfakes, those I can barely tell aren't real:

And also terrible ones, like the slop that floods Fakesbook.

I've seen funny ones, like this video of Joe Biden:

And others that, probably intending to be just for fun, turn into an epochal meme that fooled millions, like the Balenciaga Pope.

What they all have in common is that they remind us how unprotected we are from information that appears to be real but is completely false.

(I will focus on deepfakes with a strong visual component because we're visual animals and images/videos work better on social media but audio, poetry, music, and essay writing are also scary good—effortlessly indistinguishable from their human-made counterparts.)

The word deepfake carries the connotation of something ugly and dangerous. Something intended to conceal and deceive. A tool for saboteurs and underground agitators, a powerful means of disinformation. A brainwashing machine with unprecedented scope, accessibility, and, worst of all, cheap. There's truth to that: Propaganda is the bread and butter of governments and PR agencies; deepfakes are the latest addition to their population control arsenal. As they are to the toolkit of the malicious actor.

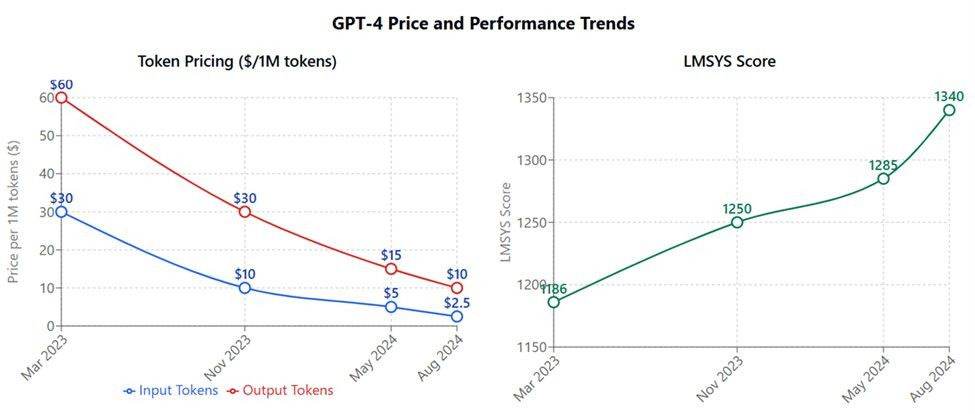

It's still cheaper to tell fake from real than make an effective fake but this consolation may not last. The cost of generating one word or pixel is trending down to zero as performance keeps increasing:

When faced with the deepfake challenge, some people keep their sanity by convincing themselves that weaponized AI is a worry of deluded conspiracists. Or, if they're unaware of the state of the art—as most are—that the quality of AI-generated images and videos isn't good enough to mislead them. This picture of a nonexistent Google TEDx speaker suggests otherwise:

Or these of drunk kids at an after-hours party. And that's August 2024; knowing how fast these things move imagine how many pictures you’ve already seen that were fake but you thought were real:

Even video.

That Joe Biden clip is just a modification of a real video with fake audio and fake lip movement. The Tom Cruise short is a face swap with some random lookalike. Or take the girl below. She’s not real but it’s “just” an image extrapolated in time to simulate human movement.

But 100% fake videos are around the corner. Google DeepMind’s Veo 2 is state of the art (Meta Movie Gen and Tencent’s Hunyuan aren’t far behind) and it is scary good:

I mean, this video is not real:

Nor is this one:

Nor this other one:

So it seems people might be better off abandoning their brittle defenses against the deepfake deception threat. They’ll be cheaper over time, they're not a conspiracy, they’re accessible and don’t take much time to make, and, to repeat a tired maxim, “this is the worst quality they will ever be.” Worry seems justified. Misinformation will catch you off-guard.

That’s fine. My issue with this kind of fear, because I have one, is that it stems from an implicit premise that has long gone unexamined. It is the assumption that deepfakes are primarily vectors of deception. I don’t think that’s true. Let me explain.

People believe that easily spotted, bad-quality deepfakes are innocuous because they think quality, and by extension, the ability to deceive, is the key metric. Well, bad deepfakes aren’t actually innocuous in practice. Just look at the fake video of Volodymyr Zelensky during the peak of the Russia-Ukraine war. It’s terrible. It got viral anyway. Quality is, surprisingly, pretty much irrelevant to a fake’s potential impact. It might even be counterproductive.

The reason is that the real power of the deepfake doesn't lie in how well it can deceive, but in how well it can express.

Do you think that Biden clip fooled anyone? Nah. It was unremarkable quality-wise. But it didn’t matter! The person who made the US President say, “My fellow Americans, I want to take a moment to address some of the hateful shit you’ve been talking about me” didn’t want to deceive us but share a feeling. It was a way to criticize the comments that were circulating about Biden’s declining mental health, not to make Americans feel betrayed by the insults. That’s why it got 10 million views and nearly 200 thousand likes.

From this perspective, a deepfake is more like satire than propaganda. A powerful new means of expression. Being worried about it is justified—only for a completely different reason.

III. We believe what we want to believe

My hottest take on the topic is that a popular deepfake is, socially and artistically, and against all odds, not that different from a great human-made piece of art.

Don’t kill me yet.

A deepfake tells a story, fictional or not, that directly alludes to our emotions. It doesn't intend to change our minds—because it can't. Deepfakes don't change our minds. We worry about how they could deceive en masse those poor gullible others (not us, of course), but it just doesn't happen. We aren’t that credulous, what we are is stubborn. And we love to rejoice in our stubbornness, especially when some external element validates it further.

Much like art, deepfakes ignite what relentlessly pulses in our hearts. The more finely attuned a fake is to our preconceptions of the world—or what we believe it ought to be—the greater its power. That’s the right frame to look at the issue: we're mostly moved by things we want to believe and things we want to be real; any expressive vector pushing us in that direction—be it deepfake or art or satire—is effective.

Philosopher Joshua Habgood-Coote hypothesizes that pervasive confirmation bias does the heavy lifting in how we craft any new belief. We believe what we want to believe. Both fakes and truth work just fine for that. We don’t care. We can't care. The epistemic apocalypse, as Habgood-Coote calls it, is here but it’s always been—and deepfakes aren’t responsible for that, at least not more than any other information transmission device, including the mischievous smile of a beautiful woman that makes a man foolishly postulate the impossible.

Insofar as a weaponized deepfake hits the sweet spot between plausible and sentimental—truth or not, high quality or not—it wins.

The best deepfakes—the ones that go viral to the point of becoming acute narrative-steering memes, like Trump’s arrest—exist at the Venn diagram’s intersection between “yeah, could be real” and “I would like that to be real.” That's exciting and worthy of our attention. Deceitful information is sterile on its own, but stories that reinforce what we've already convinced ourselves of spread far and wide.

In a way, deepfakes—especially sociocultural and political ones—do best what they were invented to do: manifesting our preferred counterfactuals (things that could have happened in this universe but never did).

Take a look at this Rolling Stone story about the aftermath of Hurricane Helene. Republicans carelessly shared a fake picture of a little girl crying while holding a puppy in the middle of what looks like a flooded city.

At first, they didn't realize it was AI. They shared it because it advanced their political agenda and when the stakes are that high, anything goes.

But then they were told it was AI slop, they simply changed the story along the lines of “it's a good illustration of what could have been.” AI or not, deepfake or not, they didn't care at first. They wanted to believe it was real and once they realized it wasn't—they didn't care either.

The deepfake, as a counterfactual, did the job just fine. It is the expression of what could be, not the deception of what wasn’t that makes it powerful.

IV. The politician who wanted to be a scientist

There's a scientific explanation for why we behave like this, studied by anthropologists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber: We're not scientists at heart but lawyers and politicians.

The theory goes like this: The human brain isn't a machine designed to seek truth. If it were, propaganda and disinformation campaigns would never work—we’d detect inconsistencies a mile away. We’d go on the hunt for them. The brain is, instead, a prediction engine. It wants, above all else, for the world to be consistent. Knowing everything is impossible so our brain sets up assumptions from which our entire belief system is built. As long as those priors are fed adequately and remain undisturbed, our brain is happy and we're fine.

The brain argues itself out of the world’s inconsistencies like a politician convincing you everything’s alright.

We're better off being persuaded that our preferred beliefs are right than being convinced that they're wrong, which would force us to grudgingly demolish our edifice of truth and erect it elsewhere. So instead we allow any kind of false information, deepfake or otherwise, to influence our beliefs so long as what results from it amplifies our worldview instead of complicating it with nuance and detail.

Deepfakes, as expressive vectors, are great at reinforcing preexisting beliefs, not at changing our minds with inconsistent truths. A deceived brain is, by definition, a brain that failed to make the word consistent. It doesn’t like that so it tricks itself out of that dead end. Most times, it succeeds. There's nothing obscure about this. If you've ever tried to convince an acquaintance by exposing a truth they don't want to hear, you've surely realized how doomed the quest was to begin with.

What persuades us is what we already want to be true. But we rarely change our minds willingly. And never by surrendering to external forces.

Let me share a timely example, now that the drama about the US elections is over.

Say you hate Donald Trump. You wanted him to lose, you wanted everyone to realize he's the idiot you know he is. Suddenly a real-looking deepfake video of him saying the stupidest thing ever on TV goes viral. Your first reaction won't be: “hey, let me check if this is real or fake, lest I start to falsely believe Trump is dumber than I thought.” No. You already think he is dumb. The dumber the better. Such a deepfake would only empower that sentiment. That's good. Even if you know it's fake.

Now imagine you know nothing about deepfake technology. What changes? What is so different if you never realize you're looking at a fake? That's right, your reaction is the same—truthfulness is effectively a non-factor.

The students at Pikesville High didn’t know the recording of principal Eric Eiswert was fake. The person who shared it with 900,000 people on X didn’t know either. It didn’t matter because even as a fake, it wasn’t surprising. Whoever made the audio recording didn’t intend merely to deceive but to ignite an existing wrath against Eiswert. A sentiment he and others shared. It was not intended to conceal some truth with false information but to give people a reason to release their anger.

As historian Daniel Immerwhar wrote in a convincing essay for The New Yorker, the power of deepfakes lies not in what they hide but in what they reveal.

That’s what they are—apt at expressing what could happen; what we'd want to happen but hasn’t. Instigators of viral counterfactual worlds instead of passive catalysts of unwanted realities we unwittingly buy.

Deepfakes are the greatest threat not against the easily gullible but the terminally stubborn. They’re the finest weapon not in the hands of the compulsive liar or the corrupt politician but the charismatic leader.

The longer we fail to recognize and accept this, the more destructive they will become.

While I agree with the thrust of this post, it ignores the harm done to individuals and groups that are victimized by deepfakes. Eric Eiswert is a prime example.

I have felt since about 2018 that the end result of all of this ultimately has to be a return to and revaluation of some form of traditional arbitors of truth and institutional mediators. Eventually we'll all mostly realize that anything that happens beyond our "lying eyes" needs a trusted source of validation and authenticity. If trust is in short supply then those who prove themselves to be trustworthy over time should therefore be invaluable, yes?