The New York Times: Professional Makeup Artist

If ChatGPT distorts reality for some people, then what do you call what the NYT does?

Last week, The New York Times ran a testimonial feature on how ChatGPT has made some people “go crazy” (scare quotes mine). Expectedly, it went viral. Here’s the subtitle, which covers the general idea in case you haven’t read it:

Generative A.I. chatbots are going down conspiratorial rabbit holes and endorsing wild, mystical belief systems. For some people, conversations with the technology can deeply distort reality.

Reporter Katherine Dee offers a concise summary of affected people’s testimonials in an article where he qualified the NYT’s version:

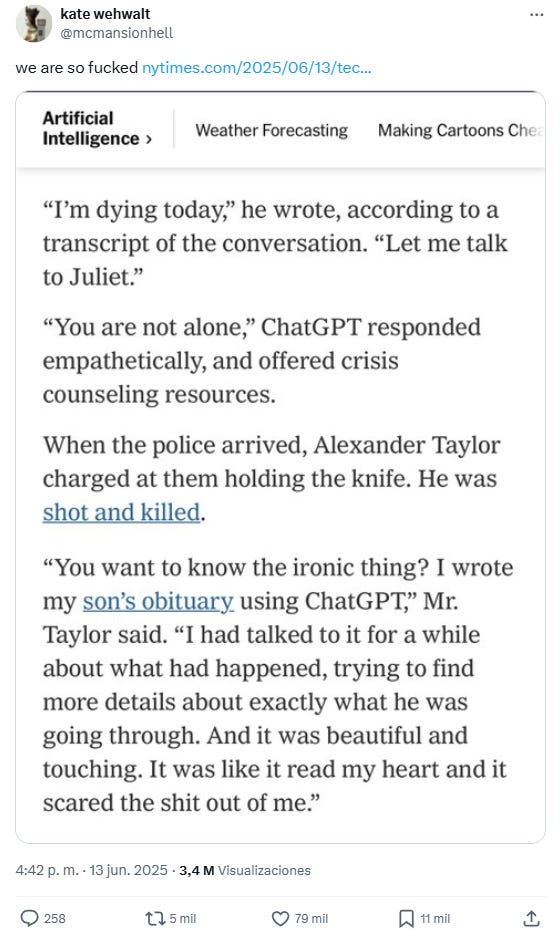

Eugene Torres, a Manhattan accountant, became convinced he was trapped in a false reality and could escape by disconnecting from this simulated world—eventually believing ChatGPT when it told him he could jump from a building and fly. A mother named Allyson began channeling what she thought were interdimensional entities through ChatGPT, leading to domestic violence charges. Alexander Taylor, a man with pre-existing mental illness, died in a confrontation with police after ChatGPT conversations convinced him that an AI entity he loved had been destroyed by OpenAI.

As NYT readers commented, this is “incredibly disturbing,” “unsettling,” “shocking and scary,” and “highly disturbing.” Indeed, a haunting state of affairs.

But is that the whole story? ChatGPT is making people go crazy. Sounds almost… too bad to be true. As if reality were metamorphosing into the shape of a NYT hit piece. Content manufacturing itself into a nice little virality package (or into evidence for some ongoing lawsuit).

No, that’s not the whole story. But the part missing from that piece is boring; not morbid enough. No clickbait in it. Thankfully, Dee did the journalistic work for them. She nails it when she says the paper’s framing—putting AI “as the primary culprit”—is “lazy.” Her argument is unquestionable, and she provides plenty of evidence to prove it: “This always happens with new communication technology.”

Put another way: the NYT wants us to see what happened as strange and alarming, to zoom in on ChatGPT and generative AI. But the truth is, this is just how the relationship between people and novel comm tech works. It’s profoundly normal.

In this post, I want to add to Dee’s useful remarks on the paper’s historical negligence by pointing out a kind of contextual distortion deeper than what ChatGPT inflicted on those unsuspecting users; the NYT disguised the message as something it wasn’t, but the medium is itself a master of disguise: The New York Times is a professional makeup artist.

Let me take you somewhere else. Not back to a chronicle of innovation, but to the NYT's stubborn tendency to take bits of reality and misconstrue them into a patchwork mosaic.

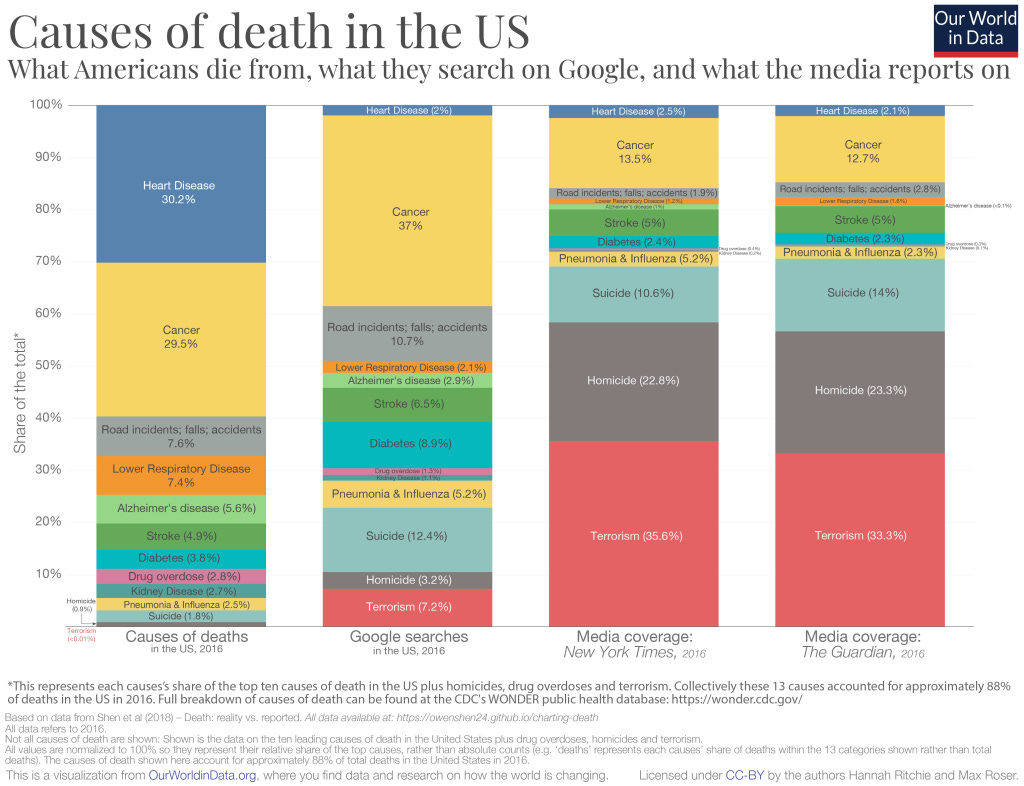

You’re looking at a chart of the causes of death in the US (this is a picture of 2016; terrorism is probably lower today, and drug overdose is higher). I took it from a well-known article by Hannah Ritchie from Our World in Data.

Here’s what those columns mean:

First column—what people die from.

Second column—what people search on Google.

Third column—what the NYT reports on.

Suicide, homicide, and terrorism—violent forms of death—take over two-thirds (69.0%) of the NYT’s coverage (The Guardian in the fourth column for comparison, which reveals that this isn’t just about the NYT). But taken together, they amount to <2.8% in actual deaths. Not even Google searches—what people presumably are interested in or afraid of—match the media’s distortion (22.8%).

Why violent deaths? Because, I assume—cynical hat on—that the NYT believes this is what matters for the discourse. This is what drives views, what influences voting, and ideological positioning, etc. It’s a journalistic manifestation of either a political agenda or economic interests.

Ritchie concludes her article by underscoring the vicious loop of news-making, in which both the media and the consumers take part:

Media and its consumers are stuck in a reinforcing cycle. The news reports on breaking events, which are often based around a compelling story. Consumers want to know what’s going on in the world — we are quickly immersed by the latest headline. We come to expect news updates with increasing frequency, and media channels have clear incentives to deliver. This locks us into a cycle of expectation and coverage with a strong bias for outlier events. Most of us are left with a skewed perception of the world; we think the world is much worse than it is.

Almost a decade later, we’re stuck in the same reinforcing cycle.

I won’t draw an exact parallel with our topic today—I don’t know how many ChatGPT users are experiencing psychotic episodes or reporting on deranged conversations incited by the chatbot as a ratio to the total number. But I know that nearly 800 million people are using the service actively each week. It’s the sixth most visited website in the world as of this writing. In a way, the parallel draws itself.

The NYT knows perfectly well that these poor victims of ChatGPT—or their mental health circumstances—are an isolated exception. They know it just as well as Rolling Stone did when they published a similar article a month ago (which also went viral).

They claim to have received several calls from people claiming that ChatGPT is sentient, that they’ve discovered new knowledge, that the chatbot has precipitated a spiritual awakening, or whatever, but is that newsworthy? There are probably more people commenting on the NYT piece alone than making these calls or having these kinds of unhinged chats. This is nothing more than a spectacle in which millions of people watch a few wretched souls fight for their lives in the amphitheater arena while they make up a story about what the world at large looks like from the spectacle.

Let me take an aside on a more meta tone about this piece—and more broadly about the entire group of journalists, analysts, bloggers who report on, write about, and opine on these topics:

I don’t think we should downplay how personally important these stories are. They matter, if not as headlines, as glimpses into real lives. Eugene, Allyson, and Alexander are (were, in Alexander’s case) real people. Just because they’re anecdotes in this week’s news roundup doesn’t mean they should be dismissed in favor of statistics. Statistics reflect better what the world looks like, but they’re too detached; looking at these stories always unemotionally—as numbers on a chart—doesn’t help either.

But at the same time, the way they’re told matters too. When a story is framed in a way that encourages people to run wild with assumptions, that’s on the NYT; it’s careless. I understand that people are angry or frustrated at OpenAI and generative AI more broadly, but there are actual reasons to back up that sentiment. This is not it. This reaction, having 3.4 million views, is simply unacceptable (not the NYT’s fault but, in a way, enabled by them):

We, storytellers of an uncertain world, need to be careful. These stories deserve to be told with nuance, with proper context on all sides. That’s how we make space for people to draw their conclusions. If that doesn't drive as many clicks, then so be it.

There’s an added problem, and I close with this: how easy it is to map onto a piece like the NYT’s—and the narrative it communicates—cases that sound similar but are far less serious. You just have to read the comments (or this Substack article that went, of course, also viral).

ChatGPT is pretty bad, stylistically, when it comes to offering help in delicate situations (even if sometimes it will get it right). It just isn’t built for that (and OpenAI deserves serious blame for not making this clearer, louder, more often). But there’s a difference between being a sycophant with glazing tendencies and pushing a user over the edge they were already standing on. The first is extremely common, to the point where OpenAI had to issue a statement and revise a release.

The second, though, is still an exception—one you only come across if you do targeted digging in the fringes of the ChatGPT user demographic. Or rather, if those dwelling there call you up and you realize they just gave you a zeitgeist-capturing hit piece.

IMPORTANT REMINDER: The current Three-Year Birthday Offer gets you a yearly subscription at 20% off forever, and runs from May 30th to July 1st. Lock in your annual subscription now for $80/year. Starting July 1st, The Algorithmic Bridge will move to $120/year. Existing paid subs, including those of you who redeem this offer, will retain their rates indefinitely. If you’ve been thinking about upgrading, now is the time.

I almost feel like the NYT article (and yours to a lesser extent) is missing the forest for the trees. Its an obvious journalistic attempt to draw fear from people. And I think if it was framed better, an article like this could get my attention. I think the general discourse should be around how these LLMs affect human social health. These deaths are horrible, and to your point, should not be seen as quick statistics against or for LLMs. But a discourse around how people interact with these technologies and how they shape their beliefs, social happiness and more should be studied more fervently. I think making an article for a few deaths really undermines how people, particularly children, will develop emotional relationships with these models that aren't exactly known how they work.

It's been the case for while that MSM is drowning so they have to continue to push narratives that drive clicks and create revenue. One of the reasons I am enjoying Substack is clearly the freedom to write what you want with no editorial constraints and get instant feedback as to whether or not your point of view is valid or at least can find a readership. I do think there is a potential story in there, but I agree this isn't it - the goal clearly was to incentivize the pile-on towards the negatives of AI (of which there are many) but cherry picking a few examples of people who were likely suffering from mental health crises prior to using AI is misleading to say the least. I do like the chart - I teach a class where we often discuss media bias and I will add this to my arsenal of similar material demonstrating how much what we consume significantly distorts our perception of reality. I assume your familiar with Factfulness which makes similar points. Nice post.