Don't Abuse ChatGPT, Kids

Or abuse it, I'm not your mom

Man is born curious, and everywhere he is… doing things like this:

Mother nature endowed us with the greatest gift of all but we can’t help being ungrateful. Or is it unwitting? I guess kids don’t read proverbs nowadays. “Give a man a fish, and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime.” All the basic advice you need to navigate the world of AI was inscribed in some dusty volume millennia ago: “Use your brain.” Or in its more sophisticated form: “Do not not use your brain.” Some people should definitely read this.

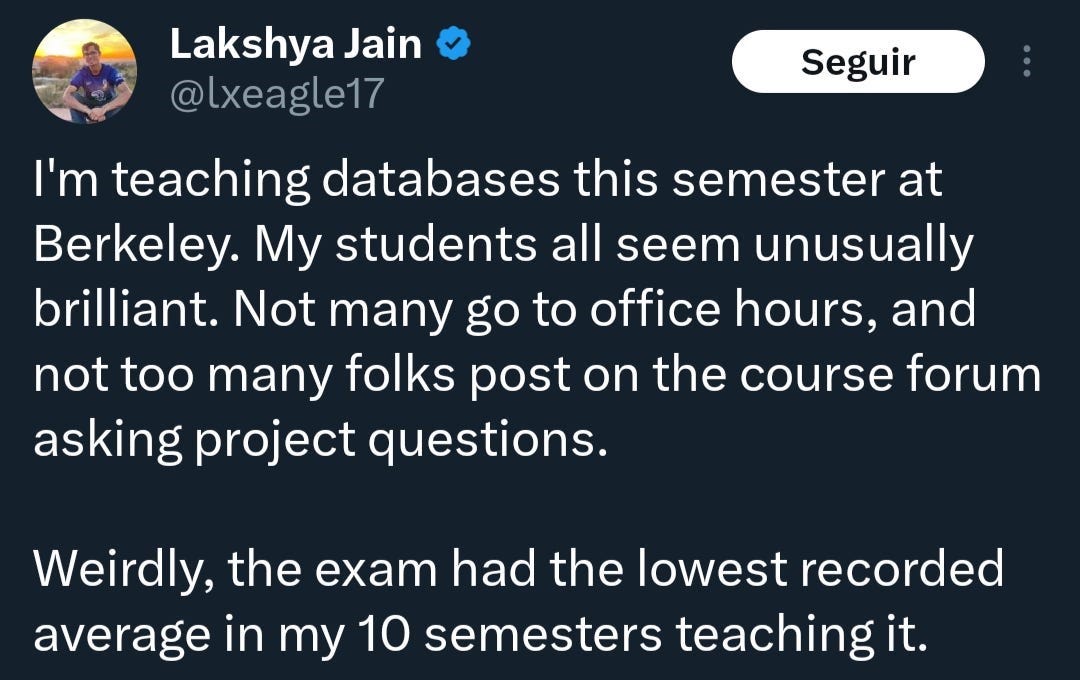

Professor Lakshya Jain is obviously talking about ChatGPT. The entire class is over-relying on it. He can’t know for sure—his students won’t tell him—but yet, again, he can. Statistical averages never lie. Well—that’s actually an important point to dig into. They never lie but can mislead. I’ve argued elsewhere that AI acts as a catalyst of character: it will drag the worst students down yet enhance the best ones. I think that natural intellectuals—or, to not be pompous, people who love to learn—will thrive with or without AI. AI will be helpful, not a hindrance, to them; like the internet before and books before that. Lazy students, however—they’re a different story.

They force us to accept that every invention, even the most inoffensive-looking, is a double-edged sword. For some reason, smart, hard-working, high-agency people always figure out how to grab the sword by the hilt whereas the dumb, lazy, unambitious bunch end up with a thousand cuts. To them, the internet is much more a source of distraction than of knowledge. Then teachers will recite to the entire class: “Be careful, young ones, for the world is full of dangers.” Don't be surprised when schools bet on caution rather than boundless curiosity; they're ruled by the tyranny of the bad student.

But perhaps I’m wrong. Perhaps AI is bad, in italics, which means very, very bad. Jain’s point is that his students scored, on average, worse than all other semesters he taught at Berkeley (for those of you who don't know what that is, it's where smart people go). Can I still say that AI acts as a catalyst of character if the average of an entire class of Berkeley students, out of ten other batches, has hit rock bottom precisely now? It looks to me that AI is maybe a laziness enabler instead (there can't possibly be that many default-lazy students at Berkeley; perhaps at Stanford, cradle of automation).

But here's why Jain’s post is worth digging into: average is not a perfect metric. The best students could be doing better than ever yet the worst doing so badly that they’d be driving the average down anyway. Wouldn't be surprised; for every student who documents her learning process in long-form Substack posts, ninety-nine indulge in TikTok binge-scrolling. The internet: distracting for the distractible. AI: catalyst of character.

Mine is, admittedly, an optimistic view that feels… unlikely—to use another statistical word that seems to convey information but means little. Actually, I don’t know. I want a happy story but I can't know and neither can Jain—his students won't tell him. No one knows, we can only believe. So, in typical human fashion, I choose to believe that what I already believe is correct and no update is in order. But, jeez, how bleak is the picture anyway?

Even if I’m right—and that's already a big if—can society survive—or better, thrive—by using as scaffolds a shrinking number of increasingly brilliant people? There might be a minimum number of giants (or cyborgs, in this case) on whose shoulders progress can rest. I realize, shaken, that if the majority of people is getting dumber—or rather, un-resourceful—we will inevitably test Thomas Carlyle’s Great Man theory of history. For better or worse.

If history is “but the biography of great men,” then our civilization should only get better for no greater men and women have ever walked this earth than those who drink (in moderation) from the wisdom well of the silicon gods. If, in turn, Carlyle was unjustly dismissing the compounding effect of bottom-up social tectonic movements, then we will perhaps end in WALL·E’s universe. Or maybe the Matrix’s. Or Ready Player One’s. Or Brave New World’s. Or Snow Crash’s. Or Fahrenheit 451’s. Or… I find it not the best augur that we insist on depicting this specific future in science fiction. Don't let us become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Anyway, as ungrateful or lazy or distractible or historically inconsequential as some students might be, I’d love it if society—as this abstract entity that shapes popular opinion and slides the Overton window back and forth—trusted them all. (By the way, that's the only sentence that matters in this post; feel free to stop reading here.)

I know it doesn’t. We collectively patronize young adult students as unable to decide by themselves what course of action is better. They are the most repressed demographic in the entire world: full of untapped potential yet coerced to not explore it at all, lest they turn to the Dark Side (that is, they choose to surrender to AI or whatever it is fashionable to fear). We make sure to answer the hard questions for them: Should they let technology ease their education? Of course not. Should they let AI help with homework if only as a means to master it? Never. Should they ignore it altogether and instead learn to speak Latin and use the quill? Maybe.

Or, perhaps—thinking out loud here—they could look for a compromise, the product of independent and inscrutable (shudders) decision-making.

I believe the sweet spot—different for each one of us—lies somewhere in the middle of the answers a typical teacher and a typical young student would give to those questions. (With “somewhere” I mean literally anywhere.) I also believe that sweet spot is only findable for each of us. Teachers can impose all they want, but they’re no better imposing a no-AI rule than a no-internet rule or a no-book rule. Or a no-glasses rule, for that matter. You can tell how useful AI will be for a given student to the same degree of certainty that you can tell whether she has good sight by looking at her. None.

They just don't know enough to be so intensely opposed to AI. Can’t they just trust that their students will aim for that sweet spot—even if they don't—and let go of the control cravings?

Confession time. I'm emotionally involved in this topic: I never did my assignments back in high school. I preferred to spend my time immersed in observation and reflection. (How lofty of me, right? At the time, I was constantly reprimanded for it; didn’t feel like a higher practice at all.) When I was not having fun with my friends in class—also reprimand-worthy behavior—I used to spend the hours looking through the window, contemplating the world beyond the sill, the trees, and the distant buildings, and projecting onto the shape-shifting clouds the thoughts that were otherwise encapsulated, trapped within those four walls and the shrunken minds dwelling inside.

And I turned out fine. I think. But the important thing is that I made those decisions myself without caring much about what teachers or society told me to do. Or, at least, without obeying them against the instinct that whispers to every young adult: “You don't know how the world works. You're better off as a mindless follower than a dead leader. So shut up and do as you're told.”

I realized early on that no one knew me better than I did so I decided I’d only follow my gut, if anything. I can tell you now: no one knows you better than you do. Follow your gut. (You can follow these words, though. They’re not advice but meta-advice.) The spiritual guides at our disposal are not always the wisest. Their intentions may be good, but that’s not enough. At best, they cast their world upon ours. At worst, they burden us with their fears and their dissatisfactions. An inheritance we never deserved nor wanted.

And at times they're more of a hindrance than even a sharpened double-edged sword with which you might inadvertently cut yourself a thousand times.

What I learned during those high school years, although I only put it into words much later, was that the world has more dimensions than your spiritual guides will ever teach you. I learned that you can manifest new ones into reality; that you can bend those disconcerting rules you thought were engraved in stone; and that you can, if you have the will and the determination, transform yourself into a new person. That is, perhaps, the single most important discovery I dug out in my first 20 years of life.

Let me digress a bit more before going back to AI. I think this is important.

School, society, and the people who love us through the constraints they impose on us—and, inadvertently, onto themselves—all paint the world as this unidimensional road we can only walk in one direction, protected with tall guardrails on both sides. They tell you how to walk it, where to go, and why it's good for you to be protected. The trail is traced so you don't have to blaze yours. “What's a trailblazer, anyway?” you ask. Just some social tesseract that you can't fathom from your low-dimensional life. “How do these amazing people do those amazing things?” you wonder. Quickly, think of a famous person! The funny thing is, quite literally any person you can name-drop right now—that you don't personally know—figured this out early on. No ordinary person follows the traced trail. They all blaze their own.

I realized, like them (but without having become famous or important, which I appreciate), that most limits in life are false limits that you can shatter, like an illusion conjured by a cheap magician, if only you look hard enough. Want to get out? Want to leverage the fact that AI—and technology in general—is neither a catalyst of character nor a lazy enabler but a portal to higher dimensions? Then challenge your entire world and defy the established customs and erase the rules that tie you to a status quo that wants you numb—and realize there's no road but a vast field of untrimmed wheat spikes. No trail and a million at the same time. Convince yourself that everything is possible. That you can be whatever you wish. If it feels impossible, you’re thinking small. If you have to ask, you will never know.

Crucially, once you learn how to do this you realize you can pursue this exploration to any arbitrary degree. You don't have to go all the way down into uncharted lands. You don’t have to lose yourself trying AI while leaving gaps and blind spots in your education. Both is possible. Find the weighted mix of normalcy and heroism that fits your life, your goals, your purpose. But always remember that just like there is a trade-off when using AI to do stuff, there is when choosing your life path. The more you find yourself, the more you risk losing the world.

Would I have been better off studying twice as much for college, doing all the assignments, and nailing every exam instead of dragging graduation one year after experiencing an existential crisis due to my failure to pass cleanly and some other things that would fill a book? I really don’t think so. I grew personally much more than I lost professionally. I am the person I am today thanks to an epiphany that I wouldn't have experienced had I obediently, meekly followed the trail. No one had bothered to tell me that the intra-personal dimension mattered or even that it existed. No one dared to tell me that life has nothing to offer you in exchange for 20 painful years of soul-beating study if you don't figure out by yourself—because no one at school seems to know this—that inward looking is the most important kind of looking. “Open your inner eye,” they should instruct you. But they don't. So why should we trust them with anything else? Like, say, how much to use AI? Let's not let them become a Gell-Mann amnesia curse looming over our futures.

Well, seems that I digressed a lot. Now that I’ve mentioned AI again after nine hundred words of rambling about my past life, let's go back to Jain and his class and get this over with.

Society’s one-dimensional vision sees nothing—let alone the future—so no one can truly offer good advice. Not Lakshya Jain, not me. (Not the fearful bunch proselytizing against AI left and right.) I can't know what those kids will do next—nor what they will have to face—and it’s precisely for this reason that it makes absolutely no sense to impose a trail into their minds.

Let them be. Let them fail. Let them abuse ChatGPT. Let them realize that’s a mistake. Or not. Let them make mistakes and pay the price. Let them learn without guiding their hand. Let them refuse to. Let them cheat. Let them understand why cheating is a poor choice. Let them make bad choices again and again. Let them.

Some will turn out to be a disappointment. Others will grow to become brilliant independent thinkers. Most will be inconsequential, unworthy of mention in the biography of the great people that we may one day find in the Library of Babel.

But we hate that, don’t we? The realization that we have so little control over the world, even the parts of it that lie within reach. We forget, far too often, that a kid, like a garden, is a place of nurture, not design.

Wildflowers spring from good and bad intentions alike.

"At the time, I was constantly reprimanded for it; didn’t feel like a higher practice at all.) When I was not having fun with my friends in class—also reprimand-worthy behavior—I used to spend the hours looking through the window, contemplating the world beyond the sill, the trees, and the distant buildings, and projecting onto the shape-shifting clouds the thoughts that were otherwise encapsulated, trapped within those four walls and the shrunken minds dwelling inside.

And I turned out fine. I think"

Been there, done that! Glad to know I am not the only one!

I appreciate your column. I had D average in high school. At 15, I was too busy reading Bertrand Russell & Thomas Kuhn abt modern science. First 2 years college=1.9 GPA. Second 2 years= 3.9. (Learned I loved to learn!)

Got Ph.D in Comm Research in 1987.

As a writer I use AI for research sources and writing draft scenes and notes a speaking styles. For me, it’s useful to read its suggestions but cannot provide finished material…at least not yet.