I. Sins and surveillance

Did you know you can map how artificial intelligence companies do things into the seven deadly sins? Look:

Pride: “No one but us knows how to bring prosperity and abundance to the world. We’ll do that with a weapon of mass distraction and control.”

Greed: “Let me tell you a tale about machine superintelligence while revenue doubles and profits soar with this thing that pollutes the commons.”

Lust: “We monetized sex with PornHub; dating with Tinder; and love and loneliness with Girlfriends, Inc. Tell her your secret desires.”

Envy: “We want to be an anomalously unregulated space, like social media, to collect those convos (unless you turn it off) and exploit factory workers.”

Gluttony: “We need to feed the entire public internet—tons of data created by you—into these huge AI models so they learn to almost do basic math.”

Wrath: “If you try to stop us we’ll lobby your entire world, buy press outlets’ loyalty, appoint NSA bosses, and convince your boss to replace you.”

Sloth: “An efficient algorithm that wastes less energy and water? No, not urgent. Just let these giant computers fulfill our prophecy: more is better.”

I’m not a Christian but if I had to read evil into these sins I’d swear it takes an eerily similar form in all of them: A pervasive undertone of surveillance. These are the sins of control, of monitoring, and of pattern-matching human behavior at any cost.

You won’t find pride or wrath in their official comms or terms of service, though; Google is an engine to discover online wonders, Meta is the town forum where you connect with your friends, and OpenAI envisions a calm society powered by intelligent assistants.

But they don’t care what their own terms of service say. They can change them as they please. They can circumvent them at will. While with their right hand they scrap your data to the last byte to know and influence you, with their left they sue the hell out of you if you do the same to them.

You didn’t really expect these data-thirsty vampires to throw away all the invaluable human behavioral data you’re pouring into their chatbot-shaped containers, did you?

They sin.

And they surveil.

II. Brave New Eighty-Four

The AI-surveillance combo is a story as old as social media and addiction, or internet and cybercrime. They go together, like the blades of any double-edged sword.

People now believe Aldous Huxley was more visionary than George Orwell (including Huxley himself) because authoritarianism failed yet we’ve become mindless digital addicts. They forget that modern society is a spawn of Brave New World and 1984: While we’re distracted with social media doom-scrolling and cute-looking virtual girlfriends, Big Brother Tech is watching you. Surveillance and addiction aren’t mutually exclusive; the digital drugs numb us into willing slaves who exchange our data for one more dopamine hit, unaware of how uneasy we’d feel if our desires of freedom—like a private life and the rightful possession of our time and attention—were still ours.

They stole our time and they stole our privacy so in a dark twist of fate that neither would’ve predicted, both Huxley and Orwell were right.

Let me reiterate some truths that hurt to read: Google and Apple know where you go and what you search. TikTok and Instagram know what you scroll past and where you pause to take a longer glance. YouTube and Netflix know what you binge-watch. Twitter knows what you read. Amazon knows what you buy. Spotify knows what you listen to.

Every now and then a cyber security nerd (or some tech ex-CEO) goes viral: “You really don’t understand how much they know about you!!!” People freak out for a moment and go back to their routine. The rational response is freaking out, though. These apps are powerful behavioral catalysts. They’re inputs to your mind designed to make you mindless. They modify your mental and emotional state to keep you engaged. Their goal might be mundane—making money with your data—but it’s no less perverse.

They have your drug. They have your data.

It’s Brave New Eighty-Four.

Dystopia is on the menu for everyone.

And the scariest part is that you’re so used to hearing these warnings by now that they sound boring, even borderline annoying: “I know, I know, can’t I watch this short clip without someone making me feel bad about it?” But the moment you stop to consider what we’ve lost; what we’ve surrendered in the last couple of decades, it comes upon you. We’re the frog that didn’t jump out of the boiling water.

What started out as a promise of connection, knowledge, and intelligence, turned into a nightmare so bad that the two most terrifying dystopias of the last century combined can hardly compare to reality.

What about physical surveillance?

It usually sparks worry and backlash in a way Google and Meta don’t (for some reason we trust the government less than private companies). Street cameras detect faces and recognize identities, wasn’t that something only China would do? Drones select and chase targets autonomously and AI enables fighter jets. Doesn’t sound like the best application.

It’s overwhelming. Yet, everything I’ve mentioned so far—digital and physical; from TikTok and Instagram to street cameras and autonomous drones—is old-school predictive statistics. The kind companies and governments have been implementing for years if not decades.

It has little to do with generative AI tools, created by the most sinful among the sinners.

Systems like ChatGPT have gobbled up the entire internet to understand how the world works, so they can use this power to collect a special type of data that goes beyond syntax-specific Google searches, the pauses you make watching TikTok, or street images of your beautiful face. ChatGPT and its ilk are the warehouses of human behavior. They’re designed to make you dependent on them for work and companionship, which are more fundamental than entertainment.

They’re designed to entice you to tell them who you are, what you are, how you think, how you feel, how you behave.

III. Models, humans, and governments

There are three distinct but equally powerful reasons companies want this data from you, which they can’t gather elsewhere.

First, it’s the best data to make models learn about humans and how to behave like humans.

AI experts love to tell the story that the web contains sufficient human interactions to understand how the world works from our exchanges alone. Bold hypothesis. However, the data on the web is often low-quality, context-free ramblings about topics no one cares about. It’s a window to how humans behave online. And we know damn well the internet isn’t representative of who we are, right?… Right? I want to believe Reddit and Twitter aren’t the best reflection of what a human is like.

But a “private” conversation with your virtual girlfriend or your tireless robot assistant can reveal all the secrets anyone might need to know you. That kind of conversational data is what chatbots use to pass the Turing test and develop uncanny humanoid mannerisms. Add multimodal inputs to the mix—images, voice, and video—and you have the richest, densest contextualized human behavioral data that exists anywhere.

Second, it’s the best data to understand what humans want or how to make us want what we don’t need.

TikTok’s For You algorithm, arguably the most powerful in the world, looks not only at explicit behavioral markers—likes and comments—but also at implicit cues like how much time you spend on each video, whether you rewatch or pause, etc. The internal recommender system then cross-references the data and, because it knows you better than you do, knows exactly how to keep you engaged As Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey says, it knows how to hack “your free will.”

Now imagine if TikTok also had data on what you think or feel, those dark and secret ephemeral thoughts that run through your head as you scroll but you never externalize. That’s the kind of data chatbots capture—because you give it to them. That’s why Meta, a company whose revenue model requires you to stay mindlessly engaged on an app, is now suddenly so obsessed with celebrity-based AIs.

And third, coming full circle, it’s the best data AI companies can sell to governments, along with their souls.

Behavioral data is most valuable when it feeds surveillance machines. Big Tech’s ties with the US government aren’t news. Microsoft, Google, Amazon, etc. work closely with the military, defense, and security branches of the government, mostly about cloud computing and sparsely about predictive AI.

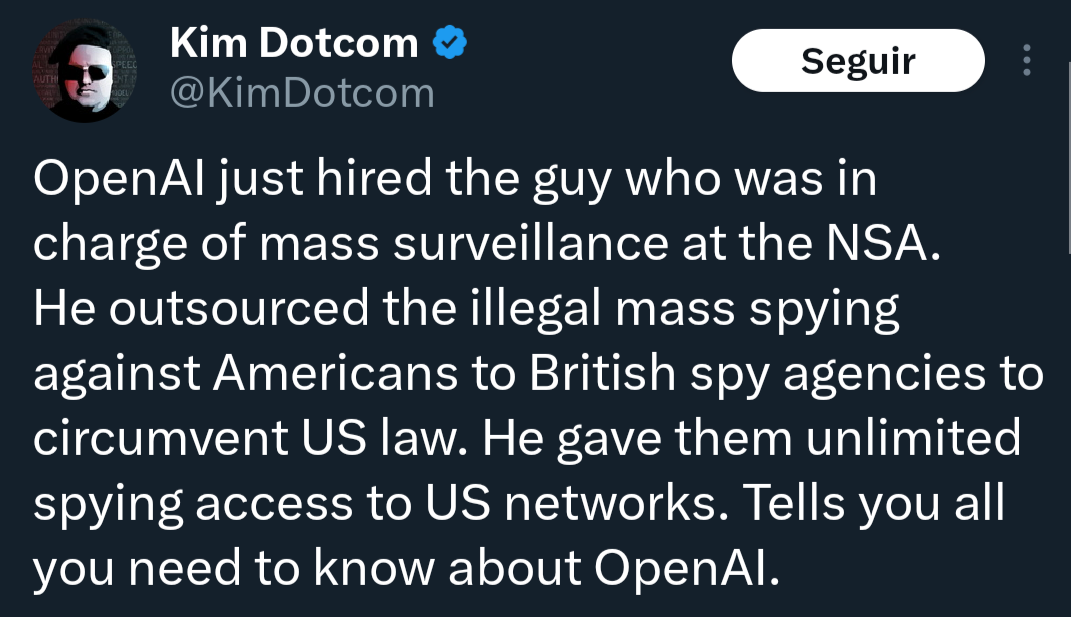

What’s new is OpenAI removing the “ban on using ChatGPT for military use and warfare” and now appointing NSA ex-head Paul M. Nakasone to the board of directors: 150+ million users talking to ChatGPT weekly for 18 months is a nice database, access to which will be paid for with a lucrative contract.

I don’t think I need to tell anyone what this means, but here it goes, from those who have ventured into the lion’s den:

“OpenAI hiring the dude who was in charge of mass surveillance at NSA is so predictable it hurts.” And it’s not just OpenAI—all of them, if not in action in spirit. They play the same game. As they grow powerful they rot; they become corrupted by the sheer weight of their ambitions and the enticing offers of those willing to do the corrupting.

Did anyone truly think artificial general intelligence—the kind as capable and smart as a human being—would remain a private endeavor; a decentralized endeavor? No one can be that naive.

The government bought the story and they’ve now ensured a funnel to buy the data.

They sin.

They surveil.

And they no longer hide either one or the other.

Tech companies and governments have made the public believe that sharing their information is okay as long as they have nothing to hide (e.g., they are not doing anything illegal). Nothing further from the truth. It conflates having "nothing to hide" with being unaffected by surveillance. Everyone has personal information they wish to keep private, whether medical records, financial details, or personal communications. Privacy is not solely about hiding illegal activities.

Privacy is a form of power—the more others know about you, the more they can try to predict, influence, and interfere with your decisions and behavior. This undermines individual autonomy and democracy itself.

Your inspired essay serves as a wake-up call for our generation, but perhaps less so for the next ones. Having interacted with younger generations for the past 15 years, I've come to admire their sharp minds and adaptability.

I believe they are well-informed about the consequences of each interaction with their favorite apps.

Have we really seen the effectiveness of behavioral prediction generated by precise targeting of individuals? Are younger generations more avid consumers than their elders? I don't think so.

It's true that with the rise of totalitarian regimes worldwide, one might think governments could seize individual data and target operations against certain categories of people. But if that's really what we should fear, young people will know how to hack and "pollute" these databases.

Their tech-savviness and rebellious spirit are our best safeguards against dystopian scenarios. While vigilance is necessary, I trust in their ability to outsmart those who seek to control them.

The future is not written yet.