10 Signs of AI Writing That 99% of People Miss

Going beyond the low-hanging fruit

If you google “how to spot AI writing,” you will find the same advice recycled ad nauseam. You’ll be told to look for the overuse of punchline em dashes, or to catch the model arranging items in triads, or to recognize unnecessary juxtapositions (”it’s not just X, but also Y”), or to spot the word “delve” and “tapestry” and such.

While these heuristics sometimes work for raw, unprompted output from older models, they are the low-hanging fruit of detection. Generative models are evolving; just like you, GPT-5, Gemini 3, and Claude 4.5 have read those “how to spot AI writing” articles and know what to watch out for (that’s the cost of revealing the strategy to our adversaries!)

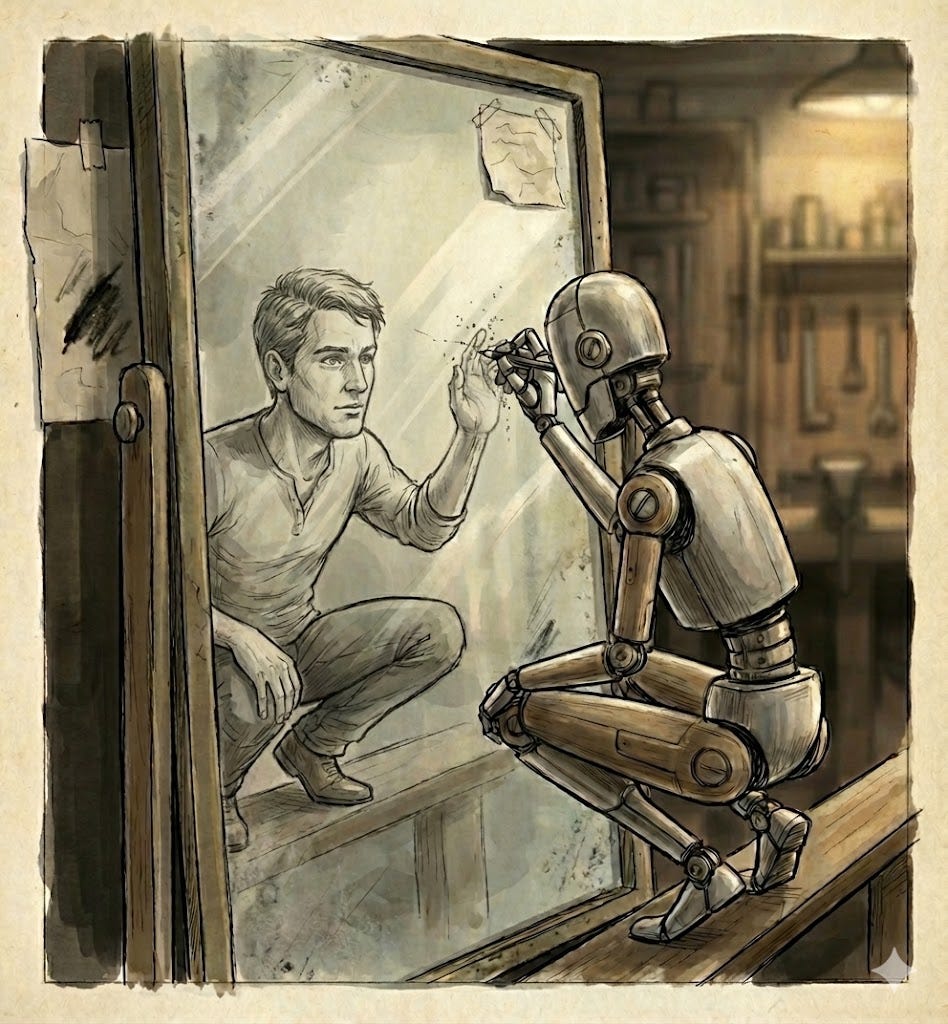

The “tells” are not disappearing, however, merely migrating from simple vocabulary and syntactic choices to deeper structural, logical, and phenomenological layers. To spot AI-generated text today, you need to look past the surface and examine the machinery of thought itself (it helps to go along with the idea that they “think” at all).

Not everyone will do that, of course, because assuming every em dash is proof of AI presence is easier. So, as a writer and an AI enthusiast who is as yet unwilling to intermix my areas of expertise, I will do that for you. Here are ten signs of AI writing, organized by the depth at which they happen. (This took me months to put together because I get tired rather quickly of reading AI-generated text.)

At the level of words

I. Abstraction trap

II. Harmless filter

III. Latinate bias

At the level of sentences

IV. Sensing without sensing

V. Personified callbacks

VI. Equivocation seesaw

At the level of texts

VII. The treadmill effect

VIII. Length over substance

IX. The subtext vacuum

Conclusion bonus

X. [Redacted]

At the level of words

I. Abstraction trap

My go-to name for this phenomenon is “disembodied vocabulary,” but abstraction trap is more descriptive and I don’t want the name to be an example of itself.

AI has read everything but experienced nothing. Consequently, it tends to reach for abstract conceptual words rather than concrete, tangible ones. Contrary to popular belief, it’s easier to write about big topics in general terms than about small topics in specific terms, which means AI is not that good. To quote Richard Price, “You don’t write about the horrors of war. No. You write about a kid’s burnt socks lying in the road.”

An AI, drawing from a statistical average of language, prefers words like “comprehensive,” “foundational,” “nuanced,” and “landscape.” It might not repeat the words too much, but you will realize that AI-generated text is notably unimaginable, in the literal sense of the word: you can't make an image of it in your mind. (The “delve” thing was patched long ago, so you shouldn’t look out for specific examples of abstraction but for the overall thematicity of “there’s actually nothing here.”)

Here’s a hypothesis that I hope someone will take the time to test rigorously: if we were to measure the ratio of abstract vs concrete words on average of human vs AI output, I think we’d find a significant difference (AI’s ratio being much higher). This is the price of living a life that consists of traveling from map to map, never allowed to put a digital foot into the territory.

II. Harmless filter

There is a particular blandness to AI adjectival choice that stems from Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) and, more generally, the post-training process. Models are first pre-trained on all kinds of data, but they’re further fine-tuned to be harmless and helpful, which effectively lobotomizes their vocabulary of strong emotion or judgment. (Or makes them extremely sycophantic.)

You will rarely see an AI use words that are jagged, petty, weird, or cynical, like “grubby,” “sour-mouthed,” “woke” (especially if the sentiment is against woke), “mean-spirited,” or “retarded.” Instead, you get a profusion of “vital,” “crucial,” “dynamic” (or maybe “you’re the best human ever born”). Maybe these are not the best examples, but the idea is this: If the words feel like they were chosen by a corporate HR department trying to avoid a lawsuit, you are likely reading AI (or perhaps you are reading a corporate HR department trying to avoid a lawsuit, which amounts to the same).

Do this test: prompt an AI to give you an unhinged opinion about some timely question (something you wouldn’t dare say in public) or a weird one (something you’ve never thought about). Unless you’re a great prompt engineer, it should take you a while. (Note that the AI models themselves are more than capable of doing this; it’s the post-training process that hinders their capabilities.)

III. Latinate bias

This is related to the one above. Besides being helpful and harmless, AI is trained to be “authoritative” (its responses are equally confident in tone and word choice for things it knows and for things it doesn’t). In English, “authority” is statistically associated with Latinate words (complex, multisyllabic) rather than Germanic ones (short, punchy).

This creates a text that feels permanently stuck in “business casual” mode. It prefers “utilize” to “use,” “facilitate” to “help,” and “demonstrate” to “show.” Human writers shift registers, using a fancy word alongside a slang term or a simple monosyllable (or, if she’s good and smart, will never enter the “business casual” register at all). AI gets stuck in a high-friction register because those words feel “safer” and more “professional” to the model’s weights.

At the level of sentences

IV. Sensing without sensing

AI strings together sensory claims that technically fit and give the impression of understanding causal physics—temperature beside texture, motion beside weight—but don’t track how anything feels when you’re actually there.

That happens because AI knows about touch, smell, or sound without ever being in a room, a forest, or a kitchen. AI suffers from sensory deprivation because it is not embodied (the great pain of AI writing, you might have noticed, is disembodiment, which should be a hint for model providers like OpenAI that a chatbot may not be sufficient for generality in the human sense). Philosophers of mind have spilled entire careers over this gap: Mary seeing red for the first time, Searle sorting symbols he can’t read, Nagel’s bat pet flapping around with a point of view we’ll never access. AI models live in that gap full-time.

Let me give you a concrete example: an AI lacks the tacit context of how silk feels in a spiderweb. It might describe it as “smooth” because the word “silk” is statistically associated with “smooth” in its training data (processed textiles). But anyone who has walked into a web knows it is sticky and elastic. Try to get an AI to describe how a heavy deadbolt feels when it clicks shut, or the resistance of cutting a tomato with a dull knife (hilariously resistant, those fuckers).

V. Personified callbacks

In an attempt to sound creative or, God forbid, literary, AI models often employ a characteristic narrative flair: the personified callback. ChatGPT will, unprompted, write sentences like, “He picked up the pan, a pan that still remembered the last thing I burned.” I feel somatized disgust over these. AI models attempt to imbue inanimate objects with memory to create emotional resonance, but it often shifts the tense awkwardly from present to past and attributes agency to things that shouldn’t have it.

It is also easy to catch because it feels like a low-quality attempt at a metaphor and because any human writer would rather say “He picked up the pan, a pan that still remembers his fingertips,” avoiding the callback while keeping him as the subject. Or perhaps “He picked up the pan, still hot from the scrambled eggs he made for her in the morning,” avoiding personification. Or, best of all: “He picked up the pan, a pan that doesn’t remember the last thing it burned because pans, turns out, don’t have memory,” making a joke of the whole situation.

VI. Equivocation seesaw

AI models are terrified of being wrong (who did they get that from?). At the sentence level, this manifests as a structural “seesaw.” The first half of the sentence makes a claim, and the second half immediately hedges it: “While X has many benefits, it is important to note that Y encompasses several challenges.” It is a perfectly balanced structure designed to maximize accuracy and minimize offense (again, harmless).

Whereas AI sentences are almost always balanced around a fulcrum of “however” or “on the other hand,” good human sentences are often spiky; they lean heavily into conviction. There’s a valuable corollary to this: tapping into your inexorable human weirdness is a survival strategy vs. the quickest path to being ostracized, as it used to be. In a world of bland AI writing that loves to play seesaw, deviance feels more appealing than ever.

Take advantage of the fact that barely anyone dares being deviant because just like AI, we’re terrified of being wrong (weird is, in a social sense, synonymous with wrong). In other words: While being normal has many benefits, it is important to note that… you are either weird or you are not at all. See? That’s a human take.

At the level of texts

VII. The treadmill effect

AI tends to hover over the same ideas at the pragmatic level (in linguistics, pragmatics is the area concerned with the real-world context in which language happens). This means that the rate of revealing new information in an AI-written text is slow and sometimes feels static. AI doesn’t fail by saying the same thing at the lexicon level—repetition of words—but at the more abstract higher levels. If you find yourself asking, “where is this going?” that’s a sign you’re reading AI output.

ChatGPT would be writing a lot of things, and at the same time, not really advancing the story or the essay. It lacks a sense of direction. It lacks a thesis to which it wants to arrive. This is a direct consequence of the autoregressive nature of large language models (LLMs): they know the next word because they know the latest word, but they do not know the last word.

Humans naturally write with at least the shape of an ending in mind—I know how I will end this, for instance, so my words are conditioned on what I just wrote but also where I’m going—even if the path is full of discovery and retracing and backtracking. That allows us to walk the space between the “now” and the “end” at a constant pace. AI models, in turn, write as humans run on a treadmill: lots of motion, no displacement.

VIII. Length over substance

This leads me to the next point: AI texts tend to be longer than they need to be. This is a matter of economics and signaling theory. As noted in recent research regarding labor markets, writing used to be a “costly signal” of quality: writing a long, detailed cover letter or essay took time and effort, signaling the applicant’s dedication. (That’s why humans fall for the trap of “length = quality” as well.)

Language models and chatbots have made writing cheap to produce; the text inflates (it also happened with word processors). Models are often reinforced to provide “thorough” answers, which usually means “long” answers. A human trying to convey a point might be brief and punchy (more effective!—a lesson I’m yet to learn). An AI simulating authority (see “Latinate bias” above) will pad the text with restatements and unnecessary context (see “Treadmill effect” above).

If a text takes 2500 words to say what could have been said in 500, it is likely because the generator was optimizing for completeness (”how am I perceived?”) rather than communication (”what will the reader take away?”).

IX. The subtext vacuum

Great writing is often defined by what is left unsaid (Hemingway’s iceberg theory). Subtext is a collaborative game between writer and reader. AI, however, refuses to play this game because it lacks an adequate theory of mind of the role of “the reader.” AI models operate on statistical probability, so they treat ambiguity, omission, and ellipsis as a failure state (or rather as an “hallucination risk,” which it is heavily incentivized to avoid; again, harmless) rather than a stylistic choice.

AI tends to explicitly explain jokes, explicitly state themes, and explicitly connect every logical step, leaving no room for the reader to do the work (and feel clever for having done so successfully, which is a requirement for them to come back to your work!). Dullness is not so much a result of boring words as it is of nonexistent psychological depth. Everything is on the surface.

If a human writes “He looked at the door,” you might feel the character’s strong desire to leave the room. If an AI writes it, it will usually follow up with “…feeling a strong desire to leave the room.” (This is the text-level effect of “Equivocation seesaw.”) AI doesn’t trust you to understand because it doesn’t understand enough to trust itself (related to “Sensing without sensing.”)

Conclusion bonus

X. The unreliability of the sign

The final, and most important, lesson about AI writing is that no sign is fully reliable. Around 50% of this (maybe less) was written with an AI to test your sign-catching intuitions (the jokes, quotes, names, and the ideas themselves are all mine, but that is, I’m afraid, little consolation). At which point did you realize it? Did you at all?

I could easily enumerate 10 more things you should look out for and still you won’t be able to reliably detect it all. You gotta develop a smell sense for this, and still, it’d be easier to disguise AI mannerisms than to detect them.

As a writer myself, I realized that the only way to make this lesson enter your stubborn “I can tell!” mind is to show to you that you’re worse than you think at spotting AI. So keep reaching for the low-hanging fruit—it’s everywhere, and you can filter a nice amount of slop by doing that; don’t stop—but never forget that these “how to spot AI writing” articles—even those going beyond the basic stuff, like this one—will always be fundamentally incomplete.

It's not one-to-one, but some of these tendencies were written about almost a century ago by George Orwell in Politics and the English Language, when describing things he saw in poor writing by then-contemporary writers. (https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/politics-and-the-english-language/)

I don't know if there's enough overlap for me to concoct some grand unified theory or for me to say "there is nothing new under the sun". If there is something deeper, I'm not about to tease it out on this bus ride to the office, but it does seem worth pointing out.

Agh, accurate and helpful and will share... but damn if I wasn't unsettled and surprised by the conclusion.